Why Your Grandmother’s Portfolio Is Beating the Pros’

Your grandmother’s stock portfolio, if she has one, is probably beating most slick hedge funds with a cane this year.

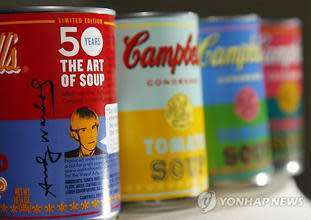

A scan of the stocks leading the rally to new index highs in 2013 reveals a pantry full of household-name, blue-chips of the sort that might have entered a conservative investment account 30 or more years ago.

Shares of Campbell Soup Co. (CPB), Clorox Inc. (CLX), General Mills Inc. (GIS), Johnson & Johnson Inc. (JNJ), Kimberly-Clark Corp. (KMB), McCormick Co. (MKC), Walt Disney Co. (DIS) and Verizon Communications Inc. (VZ) have all gained between 15% and 30% so far this year, not counting dividends, compared to the 9% climb in the Standard & Poor’s 500 index.

The relentless rise in these traditional “account-opener” stocks stretched far enough that some fast-money performance chasers seem to have crowded in, based on the way they acted in Wednesday’s mild market selloff. Most of the above stocks fell more than the S&P 500’s 1.05% drop, despite their normally defensive, less-volatile nature, perhaps as late-arriving traders were shaken out.

Slow and steady wins the race

When boring, steady, widely followed mega-cap consumer stocks lead the market, professional investors have a hard time earning their fees. Mutual funds and, especially, private hedge funds rarely own a full complement of such widow-and-orphan names, instead working to gain an edge in more obscure or faster-moving stocks with more intricate links with the economic cycle and short-term profit trends. Hedge funds as a group managed about a 3% gain in the first quarter, based on early reports from fund trackers.

Besides offering an always-welcome excuse to salute grandmotherly wisdom, the dramatic outperformance of this sort of stock tells us plenty about investor attitudes and the forces driving the so-far sturdy index rally -- in some respects challenging the standard view.

The story of the market’s upbeat start to 2013 is usually a weave of three plotlines: A receding of macro-meltdown fears due to central banks’ easy-money aggression, better evidence of economic revival and a return of long-wary investors to the stock market.

Well, sort of, but not exactly.

There is no doubt that central banks’ asset-buying offensive with conjured cash has calmed markets and smothered asset-price volatility, emboldening professional investors to lengthen their investment time horizons in search of better returns. Many observers categorically insist that it is nothing but the Federal Reserve’s regular monthly money injections more or less directly supporting stocks.

But this doesn’t quite hold up. In past periods when free money was loosed on the markets, it was the riskier, most speculative and credit-dependent investments that flew highest. Lately, small-cap shares, semiconductor stocks and lower-quality companies have lagged behind the defensive large-caps, utilities and consumer-staples names.

For sure the housing and labor markets in the U.S. are on firmer footing this year. Yet economic data also perked up the past two winters before softening up in spring, something the market is clearly on alert for this week given squishier employment and service-sector releases. And, indeed, the global-growth story is being scoffed at by the markets, with commodity prices lagging, Chinese stocks weak and Caterpillar Inc. (CAT) and Alcoa (AA) the poorest performers in the Dow Jones Industrial Average this year.

As for investors pivoting back toward equities, the evidence is equivocal. A big surge in stock-fund inflows in January spurred excitement on Wall Street, yet the sum was in large part just cash harvested in late 2012 in advance of feared tax increases, and handed to investors via tax-anticipating special dividends. There is no doubt that many under-invested institutions are boosting exposures to stocks. Yet the latest survey on asset allocation by the American Association of Individual Investors showed a lower commitment to stocks in the past month, a rarity in months in which new index records are in play.

Hunt for yield

What is certainly happening, as the popularity of the grandma stocks show, is that money is flowing into the kinds of stocks that most resemble bonds. Low interest rates indefinitely and years of money flooding the bond market has dragged yields on high-grade bonds to trivial levels, while even riskier junk debt yields below 6%.

And so, investors are feasting on the bond-like paper of private nation-states – otherwise known as the stocks of financially sturdy multinational blue-chip companies, with healthy and rising dividends, which on a tax-adjusted and inflation-aware basis appear more attractive than the static interest payouts on actual government or corporate bonds. (CNBC’s Jim Cramer has been quite good lately about explaining this whole dynamic.)

Meantime, these same sorts of companies are eagerly using their historically fat cash flows and cheap debt to repurchase their stock from the public, in effect taking themselves incrementally private in a big “capital-structure arbitrage” trade. Beginning late last year, the price-earnings multiples on the kitchen-bathroom stocks such as Campbell Soup and Clorox ramped almost in unison, the market collectively concluding that the present value of one dollar of profit from selling chowder and bleach should suddenly be much higher, given the alternatives.

Viewed this way, the large-cap stock advance looks bloodlessly rational, a matter not of economic enthusiasm catalyzing greedy purchases but rather the exchange of one sort of cheap-and-plentiful paper for a slightly less expensive type in scarcer supply. This take mutes whatever message of economic acceleration some optimists might infer from the market’s strength, while also countering the naysayers’ claim that investors are showing a dangerous level of speculative optimism.

The questions raised by this pattern of relative performance within a so-far rising market are important. Does the recent “defensive” leadership augur a choppier period for the market and downside risk to the economic pace? Are investors paying too high a price for perceived security and dividend income? Is there now unappreciated value in the more cyclically geared sectors that have been cast aside?

The way the market navigates the somewhat widely anticipated spring gut check should surface some of the answers.