2016 marked the end of the biggest bull market of our lifetimes

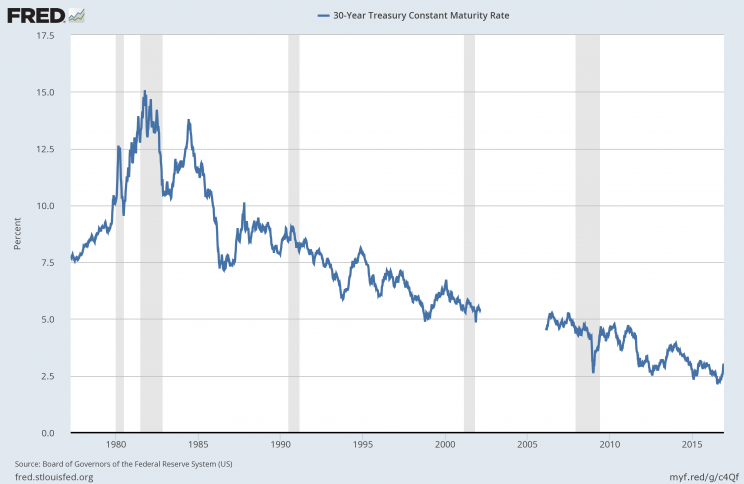

In 2016, the nearly 40-year bond bull market ended. Date of death: July 11.

And this was the biggest economic event of the year.

“The biggest of 2016, in a weird way, was not Trump, was not Brexit, was not the end of the OPEC war back in February, it was July 11,” Michael Hartnett, chief investment strategist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, said at a panel on Wednesday.

“On July 11, 2016, a couple weeks after Brexit, the 30-year Treasury yield fell to 2.088%. On that day, the Swiss government could borrow money for 50 years — out to 2076, a year most of us won’t be around to see — at a negative interest rate.

“And that day was the day that the greatest bull market ever, in the bond market, ended. Since then, yields have been rising. And that without a doubt is the biggest event of 2016.”

For many investment professionals, a secular decline in interest rates is the only reality they’ve ever known. Since the Paul Volcker-led Federal Reserve cranked interest rates up sharply in the early 1980s to end US inflation once and for all, bond yields have been on a steady decline. Bond prices rise when yields fall.

Through the decades, however, there have been episodes of yields rising. And this is not the first time strategists have called for the end of the bond bull market. But since the early 1980s — nearly 40 years ago — interest rates in the US, and most major developed markets, have been in decline.

A move towards interest rates rising, not falling, has implications not just for financial markets but the real economy, too. Rising interest rates will pressure mortgages. Rising interest rates also make it more expensive for governments, and businesses, to borrow money.

And while interest rates still remain historically low despite recent moves higher — the US 10-year Treasury yield was sitting near 2.4% on Thursday, up from around 1.8% just before the election and its record-low of 1.366% hit back in July; the 30-year Treasury yield was around 3.08% on Thursday — the increase in rates has, in part, been in anticipation of more government spending.

The only game in town

By the middle of 2016, what many had argued around the edges of economic debates for years — that governments needed to enact some sort of stimulus to aid feeble post-crisis recoveries — became a mainstream idea.

The election of Donald Trump and his plans for a $1 trillion infrastructure package certainly added momentum to the idea that Western politicians would begin doing their part to boost economic growth after central banks had been exhausted.

Hartnett noted that, beginning on July 11, interest rates went up for two reasons: the economy got better, and, more importantly, policy frameworks changed.

“The Fed said [quantitative easing] is ending,” Hartnett said. “The [Bank of Japan], the [European Central Bank] said our negative interest rate policies are not working. And then along came Brexit. Along came Trump. And along came a story of the shift from monetary policy to fiscal policy.”

And it is this shift that ushered in the end of the bond bull market.

But if we go back to the beginning of 2016, it is now clear that no piece of writing defined the conversation to be had during the year quite like Mohamed El-Erian’s book “The Only Game In Town.”

El-Erian — formerly CEO and co-CIO at PIMCO — argued that after the financial crisis, central banks increasingly became the only way for financial markets to get any support, as government and private appetites for investment dried up. This had, however, rendered monetary policy less effective over time. It had become time for a change in the approach to getting the global economy growing again.

It seems El-Erian’s idea has stuck.

A better chance on Mars

In his June investment outlook published about six weeks before Hartnett’s terminal date for the bond bull market, widely-following investment manager Bill Gross said the long-term decline interest rates, along with rising stock prices, would almost certainly not be repeated.

“With interest rates near zero and now negative in many developed economies, near double digit annual returns for stocks and 7%+ for bonds approach a 5 or 6 Sigma event, as nerdish market technocrats might describe it,” Gross wrote.

“You have a better chance of observing another era like the previous 40-year one on the planet Mars than you do here on good old Earth.”

Following Trump’s election, Ray Dalio at Bridgewater Associates wrote that the bond bull market had indeed ended. “We think that there’s a significant likelihood that we have made the 30-year top in bond prices,” Dalio wrote in a post published November 15.

“We probably have made both the secular low in inflation and the secular low in bond yields relative to inflation. When reversals of major moves (like a 30-year bull market) happen, there are many market participants who have skewed their positions (often not knowingly) to be stung and shaken out of them by the move, making the move self-reinforcing until they are shaken out.”

On Wednesday, Hartnett noted that the firm’s expectations for 2017 — US stocks to rise a little, oil prices to rise a little, bond yields to rise a little (making bond returns slightly negative) — seem pretty lackluster. But these headline predictions shouldn’t mask the huge volatility we’re likely to see under the surface.

This is the “shake out” Dalio is writing about.

“You have, much as you did in 1980-81, a massive secular inflection point taking place in the price of money, the most important thing in our financial lives,” Hartnett said. “And inevitably, as was the case in 1980-81, there is a lot of volatility, a lot of overshooting, a lot of undershooting, that happens at that particular time.”

For Hartnett, then, the biggest story of 2016 doesn’t end at the end of December.

“The story we’ve had for much of 2016, and we’ll carry into 2017, is a shift away from monetarism and into Keynesianism, away from globalization and towards protectionism, away from bonds into commodities, from growth to value, take your pick,” Hartnett said.

“But these rotations are very violent, and they’ve only just begun.”

—

Myles Udland is a writer at Yahoo Finance.

Read more from Myles here; follow him on Twitter @MylesUdland