After the recession, beware the 'jobless' recovery

The coronavirus outbreak has almost certainly triggered a recession. Probably a deep one, with massive business closures and millions of lost jobs. With luck, it will be short, with a gusher of fiscal stimulus limiting the damage. “Our economy is going to come roaring back,” President Trump said on March 17.

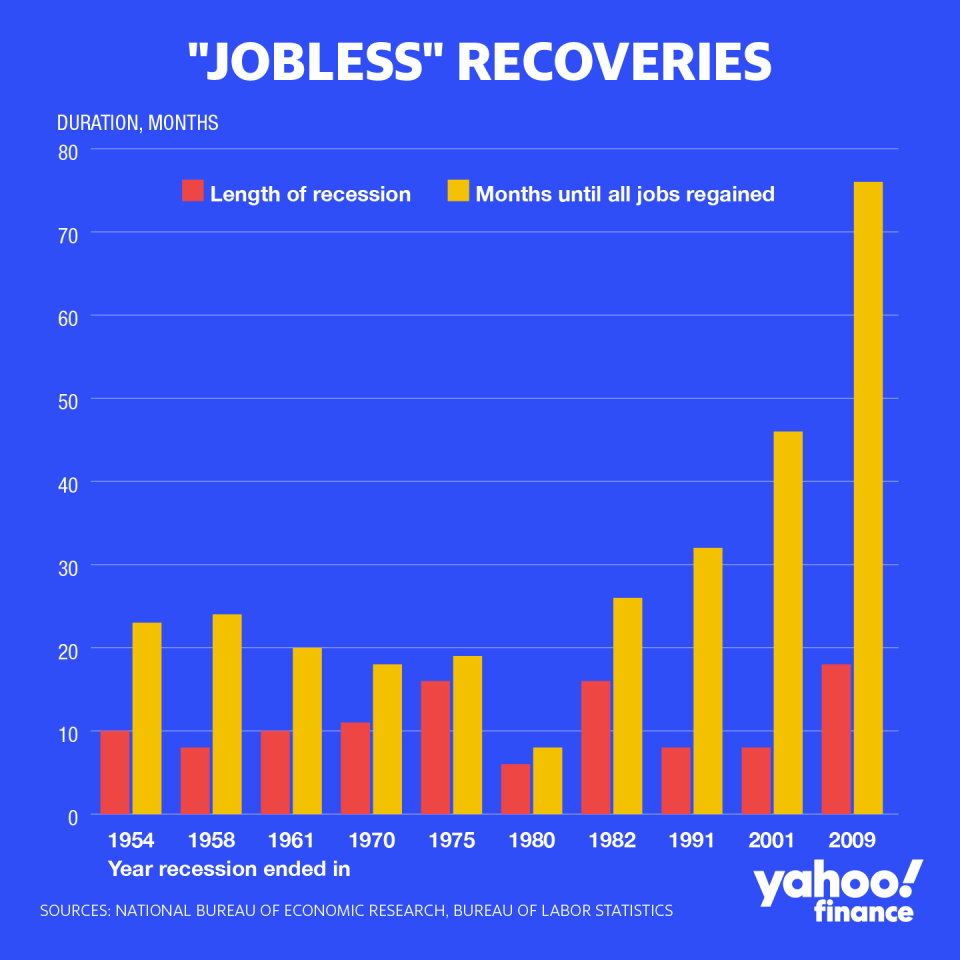

That may be overly optimistic. Beginning in 1991, each of the last three recessions has been followed by a “jobless” recovery in which the economy starts growing again, but employers remain stubbornly resistant to hiring. Yahoo Finance analyzed Labor Department data and found after the seven recessions from 1950 through the 1980s, it took 20 months, on average, before total employment reached its pre-recession peak. But in the three recessions since 1991, it has taken an average of 51 months for the labor market to heal, or 2.5 times as long.

The so-called Great Recession, which ran from December 2007 to June 2009, was the worst in modern history. It lasted for 18 months—the longest downturn since the 1930s—and total employment didn’t return to its pre-recession peak until 2014, a total of 76 months. That recession was so bad because a massive mortgage-debt bubble burst, nearly wrecking the whole financial system. Debt-induced recessions tend to be the worst type and take the longest to fix.

But recoveries were taking longer even before the Great Recession. The recession that ended in 1991 was relatively mild, yet it took 32 months for the labor market to recover, longer than more severe recessions in 1975 and 1982. The recession ending in 2001 was also mild, yet it took 46 months for the labor market to recover, the longest to date, until the Great Recession hit.

Which jobs won’t come back?

Many things are different now and it’s hard to pinpoint any single thing causing longer recoveries. But globalization and the digital revolution doubtless have something to do with it. Blue-collar jobs were a much bigger portion of the workforce before the 1990s, and many factories that slowed or closed during a recession, laying off workers, hired everybody back again once the downturn ended. Those were “V-shaped” recoveries, reflecting the shape of a chart showing employment, in which total employment fell but then quickly rose back to where it was.

Manufacturing jobs have drifted down to barely 10% of the workforce, with more people now in service jobs that don’t necessarily come back the way blue-collar jobs did in the 1970s and 80s. Companies often take advantage of recessions to retool their operations and substitute technology for labor where they can. The rising cost of health care has probably worsened this trend, since robots and computers don’t require insurance and other benefits that account for an increasing portion of total compensation.

Skill requirements also change faster than they did 40 and 50 years ago. Companies obviously want people with technical skills able to operate complex machinery or do some programming, and the pool of available talent gets a lot bigger when layoffs mount. So companies get pickier, hiring people for part-time or temporary work, that lowers their benefit costs, if they can get away with it. This happens as shareholders are pressuring companies to cut costs—i.e., fire workers and keep payrolls lean—during tough times and protect the stock price, an uncomfortable but inescapable dynamic in a free-market economy.

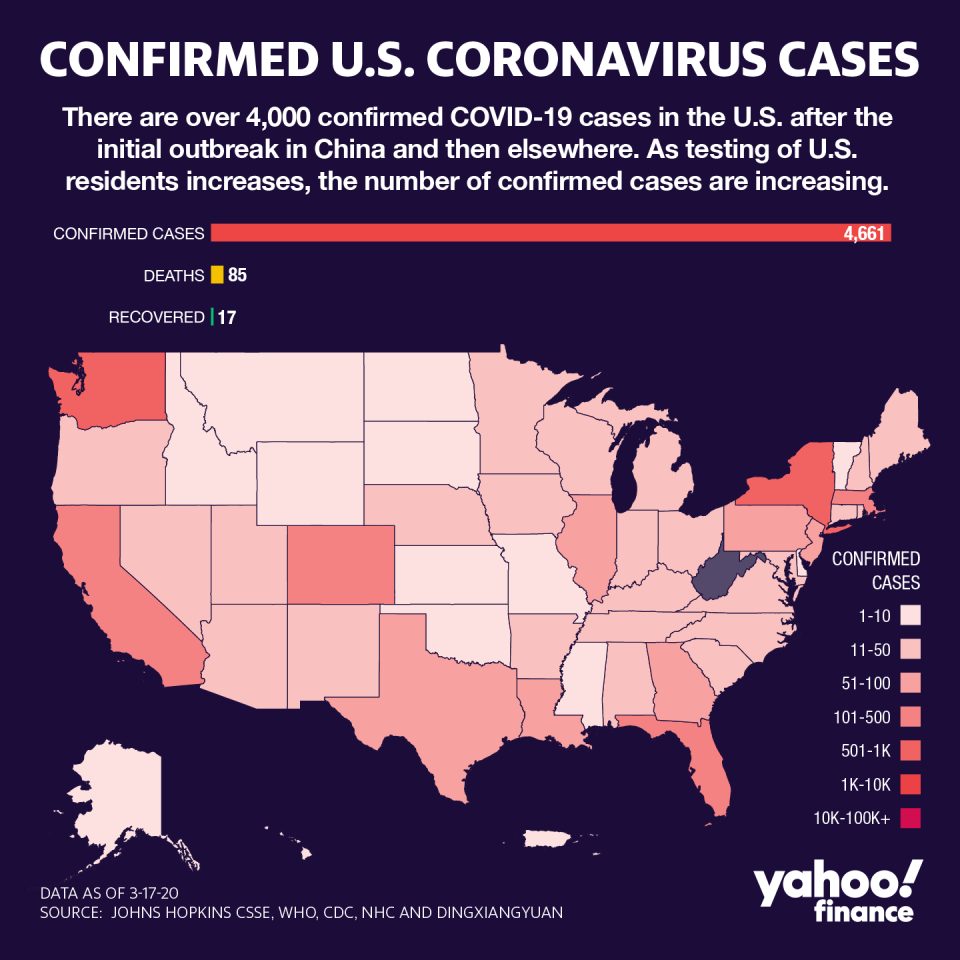

The coronavirus shutdown could kill many jobs, fast. The left-leaning Economic Policy Institute estimates 3 million additional people will be out of work by the summer. Unemployment insurance and other safety-net programs will help with short-term funding, and Congress seems highly likely to pass a large stimulus program that might send people cash directly, and do other things to tide them over. But the United States does not have good job-protection programs, and many people who get laid off during a recession find their job no longer exists when the flood waters recede.

Other countries do a better job of keeping people employed doing a recession, to minimize the career shock of trying to find work after the employment landscape has radically changed. Many firms in Germany, for instance, use “work sharing” strategies during slowdowns, with most or all employees staying on the payroll but everybody working and earning less. This spreads the pain of a recession more evenly while preventing the dislocation that comes with losing your employment status and looking for ways to start over.

While there’s interest in better ways to protect workers in some parts of the U.S. economy, there aren’t many places where it’s been codified into labor law or corporate policy. It’s possible Congress could structure the coming stimulus in ways that prioritize worker protection, a failure of the huge 2008 and 2009 stimulus programs that bailed out banks and automakers but didn’t specifically protect workers. Trump has a chance to do better, and voters will have a good idea if he does when they head out to vote in less than eight months.

Rick Newman is the author of four books, including “Rebounders: How Winners Pivot from Setback to Success.” Follow him on Twitter: @rickjnewman. Confidential tip line: [email protected]. Encrypted communication available. Click here to get Rick’s stories by email.

Read more:

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.