Why Amazon slashing prices at Whole Foods won't cause deflation

There are few things economists hate more than deflation.

So when news crossed Thursday afternoon that Amazon (AMZN) would cut prices on a number of products at Whole Foods (WFM), shares of grocery retailers plunged, and some argued this will exacerbate the Federal Reserve’s current inflation problem.

That is, the Fed can’t seem to create enough of it.

In July, inflation as measured by the Fed’s preferred metric — “core” PCE, which excludes the cost of food and gas — rose 1.5% over the prior year, below the Fed’s 2% target and the continuation of a trend this year that has seen inflation readings consistently disappoint. With unemployment at post-crisis lows, this outcome has surprised many economists.

On Thursday, Bloomberg Fed reporter Matt Boesler noted that the idea specific consumer trends in the U.S. economy could be keeping inflation down has made its way into the thinking of at least some Fed officials. Boesler noted that in the minutes from the Fed’s latest meeting, Fed officials noted, “Restraints on pricing power from global developments and from innovations to business models spurred by advances in technology.”

And this followed June comments from Chicago Fed president Charles Evans, who in an interview with CNBC just days after the Amazon-Whole Foods merger was announced hinted that this deal could have negative inflationary consequences.

“In a world of global competition and new technology, I think competition is coming from new places,” Evans said. “New partners are choosing to merge and sort of changing the marketplace and [bringing] more competitive pressures on price margins.”

But as we noted back in June following Evans’ comments, this view ignores that a decline in grocery prices frees up money to be spent elsewhere in the economy. And with consumer spending accounting for about 70% of GDP, this should be positive both for overall growth and an increase in the price of other goods and services.

As Neil Dutta, an economist at Renaissance Macro wrote, “If there is strong competition in the food retail industry and it pushes food prices down but wage growth in the labor market is unchanged, it implies an outward shift in the household budget constraint. This frees up money to spend on other goods and services, which drives up the prices for those goods and services.”

Lower grocery prices, in other words, should be inflationary, all else equal.

And as analysts at Bespoke Investment Group wrote Thursday after news that Amazon would cut prices crossed the wires, “This [news] inevitably led to breathless commentary that Amazon is a new source of deflation for the Fed to fret over. To say we disagree would be understating the point quite dramatically.” (Emphasis ours.)

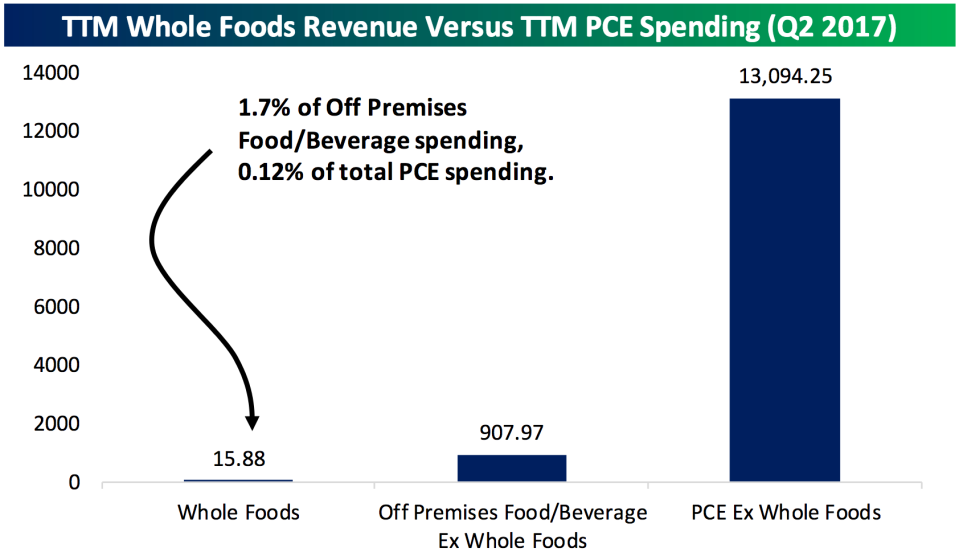

Among other things, Bespoke noted that Whole Foods itself is roughly accountable for 0.12% of total PCE spending, and that even a 10% drop in grocery prices would only take down total consumer prices by 1%. Of course, a 10% drop in total grocery prices is, to say the least, unlikely.

“The trend of ascribing mythical powers to Amazon extends far beyond the stock market and in this case into the realm of economic analysis,” Bespoke writes.

“While there are good reasons to think about the long-term macroeconomic impact of a shift to online retail, we think it’s a mistake to do so with the Whole Foods news, as some Fed policymakers have done.”

Additionally, while Amazon is the hottest story in retail right now, some question the soundness of assuming that the company will steamroll the grocery industry by cutting prices and stealing customers.

As Izabella Kaminska writes on The Financial Times’ Alphaville blog on Friday, Amazon’s price cut, “mostly serves the interests of bargain hunters who are happy to waive ‘experience’ in exchange for cheaply priced goods obtained any old way possible.” This, however, ignores the premium, upscale experience Whole Foods sells alongside its organic food.

Shopping at Whole Foods, then, is what Kamiska writes is an “overt act of conscious inefficiency.”

“If Whole Foods customers wanted cheaper organic avocados, they’d already be shopping at Waitrose, Sainsbury, Costco or Walmart,” Kaminska writes.

Which means the limits of Whole Foods’ scale in “disrupting” the grocery sector might be closer than we think. Then again, Amazon may not really be buying Whole Foods for the groceries — it really just wants the storage space.

—

Myles Udland is a writer at Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter @MylesUdland

Read more from Myles here: