How the bad guys build fake accounts on Facebook

I have a new Facebook friend—but it’s not a real person. It’s a fake. I know, because I purchased the account on the internet for $4, activated it, then sent a friend request to my personal Facebook account. (I accepted.)

Facebook (FB) is in regulators’ crosshairs because of revelations that Russian operatives used the platform to sow discord among the American electorate and discredit Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton during last year’s presidential election. Part of the Russian effort involved impostor accounts that seemed to represent ordinary Americans or American organizations but were in fact operated by foreign agents. A Russian-run Facebook account called Blacktivist, for instance, attracted 500,000 followers with provocative posts highlighting racial injustice before Facebook discovered the subterfuge and shut it down. Facebook says about $100,000 in ad purchases by Russian entities since 2015 were linked with about 500 fake accounts.

Special prosecutor Robert Mueller is investigating Facebook’s and Twitter’s role in Russia’s 2016 disinformation campaign, with execs from both companies due to testify before Congress soon. New laws governing what appears on social media sites seem likely, but first, policymakers must answer some confounding questions, including: How prevalent are fake accounts on Facebook in the first place?

Nobody really knows, because Facebook doesn’t release enough data for researchers to study the problem. In its latest securities filing, the social-media giant says that perhaps 1.5% of its 2.01 billion accounts worldwide are “undesirable.” That would be 30 million accounts. But the company also says that estimate could be off because it’s based on a “limited sample.” Other estimates from a few years back put the number two or three times higher.

Facebook fakery

Yahoo Finance decided to investigate the role fake accounts play on Facebook by attempting to establish and purchase accounts attributed to people who don’t exist. We found that Facebook does a good job detecting new accounts that are fake. But we also discovered that virtually anybody can buy fake accounts that have already been established, using no special technology, for as little as $1.50 per account. Some purveyors in this murky gray market claim to have thousands of accounts for sale on Facebook, as well as other social-media sites such as Twitter and LinkedIn. Facebook has actually stepped up policing of fake accounts, according to scuttlebutt among account sellers. Yet it’s still relatively easy to roam Facebook, make friends, engage in chats and share posts masquerading as somebody you are not.

In my first attempt at Facebook fakery, I made up a name, established an email account in that name and purchased a prepaid phone so I’d have a mobile phone number in case Facebook wanted to verify my account that way. I downloaded a couple of stock photos from a subscription service showing a man roughly my age to use as profile photos. The name on my first account was Harold Whitmoore. I asked a few colleagues to send friend requests to make him look legit, and I was up and running.

I wanted Harold to have some political interests, so he joined a couple of right-leaning interest groups on Facebook. Nothing too crazy. Around the same time, I set up another account, Rory Shandling, who would be similar to Harold demographically but liberal-leaning. As Harold and Rory got established on Facebook, I’d get a feel for what went on in the site’s conservative and liberal bubbles.

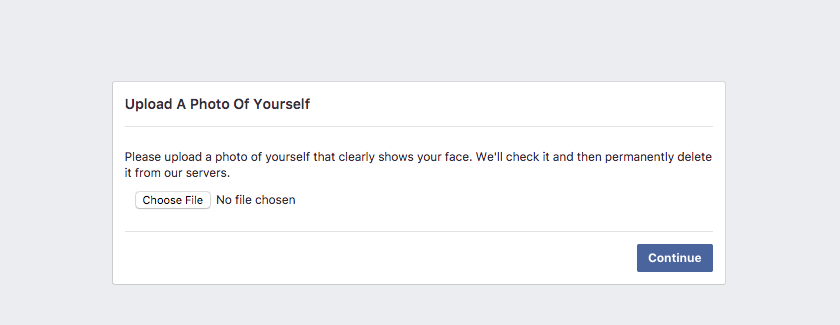

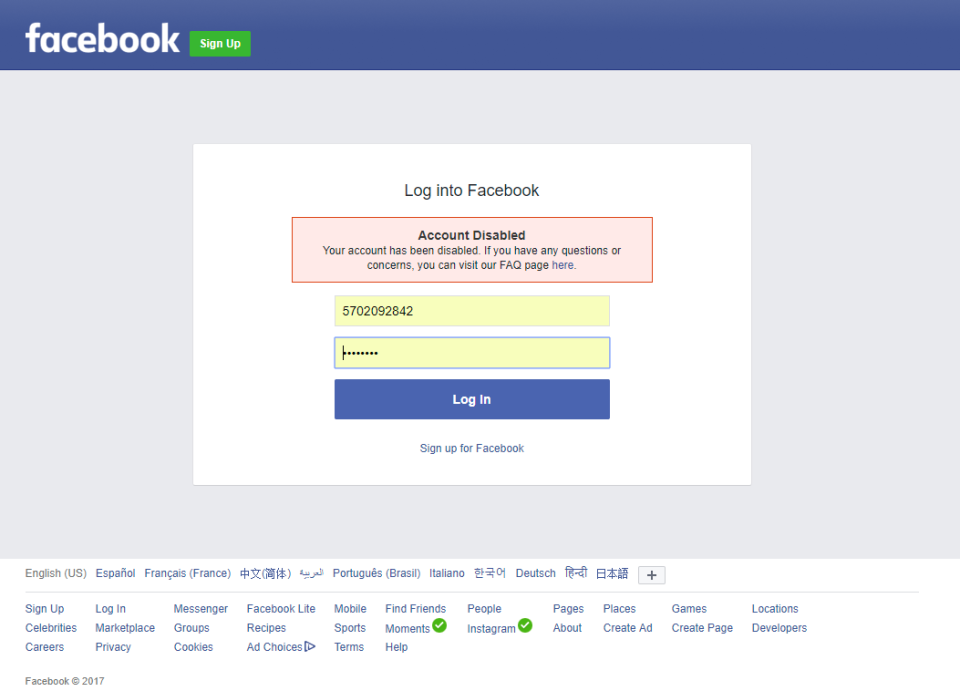

Except Facebook caught on, and in less than 48 hours the site asked for additional verification for each account. I passed the phone number test, entering the code Facebook texted me for each account. But something was still awry, and in each case Facebook asked me to upload a photograph clearly showing my face. I didn’t have any more photos of the same people in the profile pics. Foiled.

I tried being more devious, establishing fake accounts from different computers and using the Tor Browser so Facebook couldn’t track my computer’s IP address. I changed the phone numbers on my prepaid phones, because Facebook only allows a mobile number to be associated with one account. At one point, I thought my conservative persona had made it through Facebook’s security phalanx. But then I did a Facebook search for Breitbart, the conservative news organization, and the second I hit return, a strident algorithm marshaled me into Facebook’s security protocol. Game over.

A couple of sources told me it was relatively easy to buy established Facebook accounts online, so I went to sites they recommended and did a basic web search that turned up a few others. One site, available in both English and Russian, claimed to have more than 120,000 Facebook accounts for sale, ranging from old accounts established in 2006 to newer ones set up in 2016. Some were “PVAs,” phone-verified accounts. The costliest offering I found was $150 for a single account that went all the way back to 2006, which supposedly makes it seem highly legitimate. The cheapest accounts were the newest ones, not verified by phone, which cost $150 for 100, or $1.50 if you just wanted to purchase one.

I ended up buying 26 accounts from four different sites, spending about $105 in total. Two sites required payment by bitcoin. I used a credit card for another site and PayPal for the fourth. With delivery of the log-in on and password info, two of the four sites also included tips for operating the accounts without triggering Facebook’s security protocols. Examples: “Warm up” the account gradually, with just a little bit of activity at first. And keep a couple of spare photos at the ready, in case Facebook asks you to upload one. For one account I purchased, the seller actually provided additional photos, which clearly were the same man in the profile pic.

Of the 26 Facebook accounts, I was able to log into 14 without a problem and use the accounts freely. On several other accounts that were supposed to be phone-verified, Facebook told me the phone number associated with the account had been used on another account. That triggered verification procedures and the suspension of the account. A few other accounts came with invalid passwords, and since I didn’t have access to the related email addresses, there was no way for me to update those passwords.

Eight of the failed accounts came from a single provider, from whom I had ordered 10. I complained by email, and the login data for 8 new accounts arrived. I was able to log into 6 of the 8 replacement accounts. They all featured profile pictures of attractive young women claiming to be from real places such as Arkansas City, Kansas, and Delaware, Ohio. Facebook didn’t require verification by mobile phone for these accounts, but it suggested it as a security precaution in each case and defaulted to the country code for Bangladesh when prompting me for the number.

It was fascinating to poke around in accounts that seemed to have been set up a few years prior specifically for illicit use in the future. Several used email addresses ending in .ru (designating Russia) as the log-in ID, which apparently is not a problem in itself. Other accounts had associated phone numbers from Germany and Austria, for people who supposedly lived in American locales such as Milwaukee, Idaho Falls and Anchorage. Many of the fake accounts had no Facebook friends, but I logged into one account to discover 219 pending friend requests. It’s probably no coincidence that the profile photo showed yet another pretty young female.

Scammers, troll farms and bogus businesses

Facebook is well aware of this gray-market activity. “We understand there are all these different marketplaces out there,” a Facebook security official told me. “When you’re dealing with things at the 2 billion–user level, automation is key. Many times these actors are overseas in places that are uncooperative, places where Facebook as a company wouldn’t have a great effect.”

Russian intelligence agencies reportedly have their own sophisticated “troll farms” where they build and operate fake social-media accounts. But they might also shop on public sites every now and then. “A nation-state can approach this kind of toolkit with nation-state resources,” says Graham Brookie, a former cybersecurity expert on the National Security Council under President Barack Obama who’s now with the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab. “But they don’t have an exclusive interest in sourcing all of this stuff in-house. If they’re trying to make a message diffuse, they want it to come from a number of different angles.”

Scammers also use fake social-media accounts, to solicit money for bogus business ventures and other schemes. Marketers are interested in such accounts, too, and there’s a lot of discussion in online chat groups about how to use fake Facebook accounts to sell lipstick, pet products, online advice and everything else under the sun. That’s because endorsements from real people—or bots seeming like real people—are often more effective than paid ads.

“It creates the fa?ade that real people are engaging in whatever you’re trying to sell,” says Brookie, “whether it’s political or commercial or a pair of sneakers.”

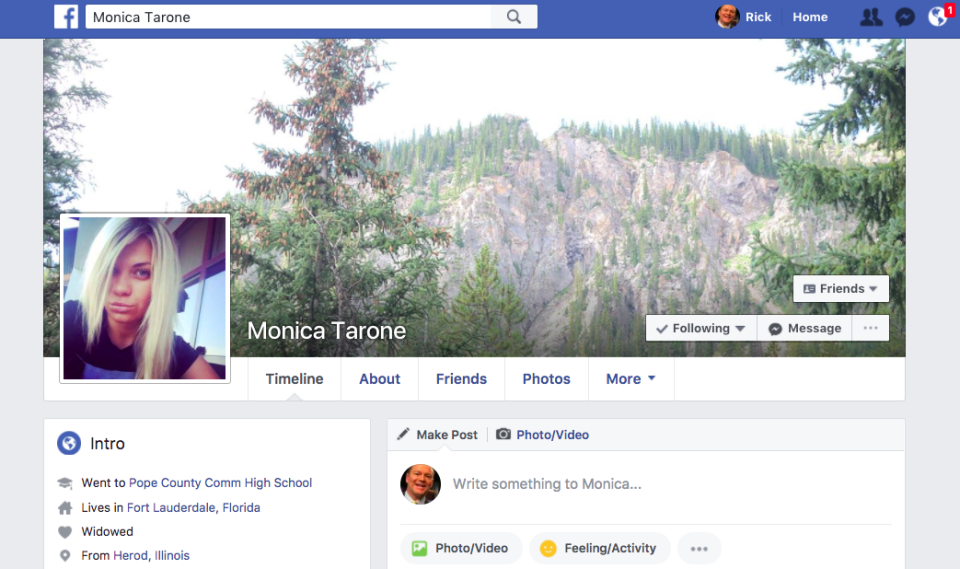

The fake Facebooker I purchased, and became friends with, was “Monica Tarone,” a pouty-looking blonde woman who looked to be about 20, even though Facebook listed her birthdate as February 13, 1954—which would make her 63. I downloaded her profile picture and conducted a reverse image search to see if the photo had been appropriated from somebody else’s social media account or another internet site. No hits. The photo could have been purchased legitimately from a stock-image site. And there’s always the chance it was taken by whomever established the account.

Monica’s account was apparently created in 2014, and when I bought it, she had 62 friends, which made me her 63rd. Some of those friends were obviously fake themselves. “George Joe” of Houston and “Steve Robert” of Colorado Springs each had the exact same profile photo, for instance—and a reverse image search suggested it belonged to a Romanian police chief whose online photos have been stolen for use in a variety of scams. Monica had one friend named “Tommy Davis” and another called “Tommy Davis Davis.” The first Davis’s account includes a profile pic that has appeared on several other web sites under different names, while the pic accompanying the second Davis appears to be Australian actor Peter Cassidy. Another friend called “Steven Anderson” listed “colonel at American Army” as his occupation. If that were a real colonel, his employer would be the U.S. Army, not the American Army. And a surprising number of Monica’s friends were widowed.

Monica also had some real friends, however. She appears to have buddied up with about a dozen actual people in Billings, Montana, including two men who wished the fake Monica happy birthday when her date came up in February this year. Most likely, whoever built the account was able to persuade one gullible resident of Billings to accept her friend request, which made her seem like a legitimate person to others in Billings when she asked to link up with them on Facebook. That fits the profile for successful bot accounts—linking with fakes can boost the number of friends or followers, while real connections give the account a measure of credibility.

Still, one sought-after friend in Billings expressed skepticism about Monica Tarone. “Monica, how do you know me and why would you want to be my friend?” he wrote on her timeline in 2014. “Sorry,” she answered. “I am new to this and they just gave me a list to become friends so I started checking people on this list!” He seemed to buy it—and they became friends.

In a statement, Bill Slattery, head of eCrime investigations for Facebook, told Yahoo Finance there’s nothing new about fake accounts on social media sites. “The anti-abuse systems we’ve built to detect suspicious activity make it harder for criminals to create and hold onto these types of accounts once they try to use them,” Slattery said. “Just because an account looks available for sale, that doesn’t mean it’s actually valid or that it can be used effectively for anything without getting caught. We make it very difficult for the accounts to actually be used for harm, which disrupts the financial incentives for the scammers. And, in addition to our fake account detection systems, we make reports to law enforcement when appropriate.”

Facebook isn’t the only social-media site grappling with fake accounts. Researchers think as many as 15% of all Twitter accounts may be operated by bots or impostors, and it’s generally easier to establish a fake account on Twitter than on Facebook. Hackers have set up accounts on LinkedIn, attempting to connect with legitimate users to “scrape” their personal details for use in other fake accounts, and even to conduct cyberespionage on companies those users may work for. Sometimes a fake operator will have accounts on various social-media sites that link with each other and appear to be the same person.

But Facebook, with its 2 billion users around the world, has four times the reach of LinkedIn and nearly seven times the reach of Twitter. It will also post about $16 billion in profit this year, giving it the means to police users who are on the site to exploit others. If it can find them.

Confidential tip line: [email protected]. Encrypted communication available.

Read more:

Rick Newman is the author of four books, including Rebounders: How Winners Pivot from Setback to Success. Follow him on Twitter: @rickjnewman