Why Barnes & Noble still has value for the right buyer

An activist hedge fund is pushing for Barnes & Noble to sell itself—and the bookstore chain is open to it, according to the Wall Street Journal. The stock popped 16% on the news, which certainly amounts to a ringing endorsement from shareholders.

Sandell Asset Management has “acquired a meaningful ownership stake” in Barnes & Noble, and its public letter to the B&N board comes out swinging in favor of the chain’s staying power. “It is our contention,” Sandell writes, “that physical books, and physical bookstores, are not going away anytime soon.” Sandell thinks Barnes & Noble will fare better “as a private entity or as a division within a larger organization.”

In a statement, a Barnes & Noble spokesperson said that no one from Sandell had even reached out to the company yet, “but we welcome constructive dialogue with all of our shareholders.”

So if Barnes & Noble is on the block, who would want it, and why?

The chain’s stock is down 25% this year, and 52% in the past two years. For its fiscal year that ended in April, revenue dropped 6.5% to $3.9 billion, and it warned that it expects sales to drop again in 2018.

On the other hand, the Q4 results beat analyst expectations, a trend in the right direction. Loss per share was not as bad as predicted, and quarterly revenue was higher than predicted.

Sandell argues that Barnes & Noble’s current market cap ($520 million at the time of its letter, though it has since risen to $600 million) is “unconscionably low and fails to reflect the true value of the Company.” Sandell thinks B&N could fetch offers of $12 per share (it’s currently at $8), which would come to nearly $900 million, a healthy premium.

And Sandell isn’t crazy to think so. Believe it or not, Amazon has not entirely killed brick-and-mortar bookstores.

Barnes & Noble has more value than people assume

For the first few years after Amazon launched Kindle in 2007, the popular narrative in the bookselling world was: Amazon is killing bookstores, and e-books are killing printed books. And indeed, Borders, which liquidated in 2011, was a casualty of this time period.

But Barnes & Noble has only closed 75 stores since 2011, and still has 630 locations, a number that may surprise many who assume the chain is gasping its final breaths.

Meanwhile, e-book sales fell 17% overall from October 2015 to October 2016, according to the Association of American Publishers (AAP), though its metrics exclude some categories, like self-published e-books. And a recent report (granted, a report from Barnes & Noble College) finds that Generation Z students (those born from 1990 to 2000) prefer print textbooks to digital.

Another assumption many shoppers might make (such as any who buy their books almost entirely on Amazon) is that Barnes & Noble is the last remaining brick-and-mortar bookstore chain. That’s not the case: Books-A-Million has 260 stores in 33 states, and Half Price Books has 121 stores in 17 states. (And yes, now Amazon, too, has 13 physical bookstores.)

Barnes & Noble has tried to adapt to the new demands of physical retail by turning its stores into hangout spots, making them more experiential. Many Barnes & Noble stores now have a Starbucks counter inside them (Starbucks licenses these out to big chains like Stop & Shop), and the stores offer a lot more than paper books.

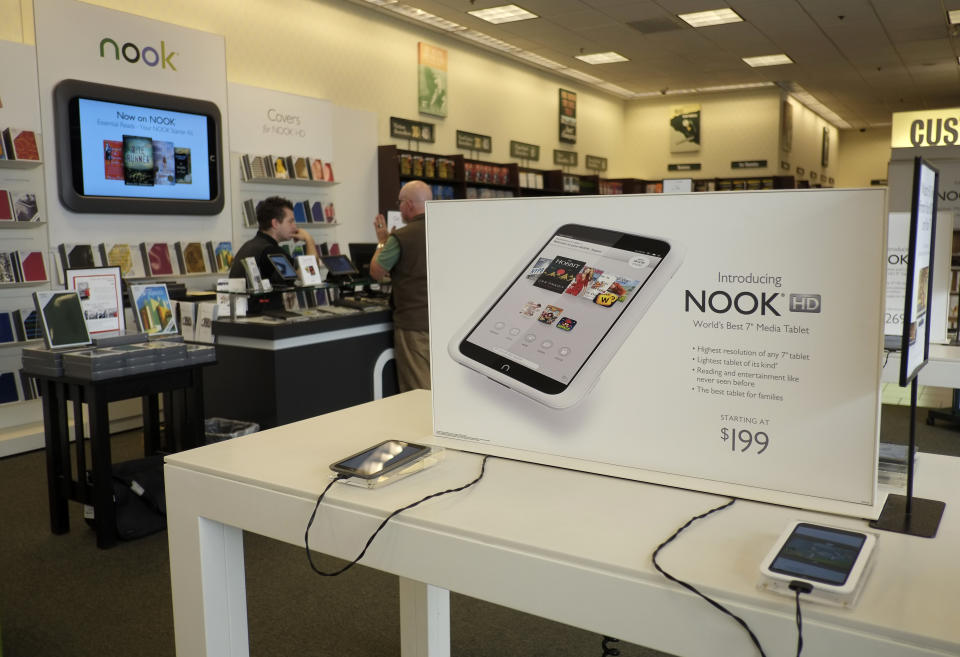

Walk into a Barnes & Noble today and you’ll find a corner dedicated to its Nook e-reader, as well as toys, gift wrapping, board games, and other assorted book-adjacent merchandise. (Of course, you can get those things on Amazon, too, but you can’t touch them.)

There was a time when Barnes & Noble was the big, bad threat in the eyes of small, independent bookshop owners; now, with Amazon eating the world, Barnes & Noble has become, in a way, one of the underdogs in bookselling.

All of these are legitimate indications that the right operator could take Barnes & Noble private and turn it around.

Who could buy Barnes & Noble?

The first instinct many people have, on the news that Barnes & Noble might be for sale, is that Amazon would want it. And while Amazon (and its acquisition-hungry CEO Jeff Bezos) might indeed want it, and could certainly afford it, it likely can’t, and won’t, try to get it.

That play would not fly with regulators.

Amazon has successfully avoided any real antitrust challenges in its history of M&A because it has not bought anything that gives it an unfair share of any business. Buying Whole Foods, for example, is fine with regulators because Amazon did not previously have any significant share of brick-and-mortar grocery. (And Whole Foods itself doesn’t have a large share, either.) But if it tried to buy Barnes & Noble, that would give it the lion’s share in brick-and-mortar bookselling, when it already has the lion’s share of online bookselling. “That would be a problem,” says analyst Jan Dawson.

Of course, even though Amazon is an unlikely buyer, this is still an Amazon story, because the retail giant is the largest threat to physical bookstores (and, increasingly, to a number of other physical retail categories). There were already whispers in the book industry, after Amazon announced its intention to buy Whole Foods last month, that an Amazon competitor could see that deal and, in turn, try to make a play for Barnes & Noble.

Who might that competitor be? Walmart comes to mind.

Walmart considered buying Barnes & Noble back in 2010. As part of its consideration, Quartz wrote in 2013, the retail chain “contemplated continuing to sell some of the books in retail Barnes & Noble bookstores, but adding its own best-selling items.”

That sounds exactly like what Amazon is about to do with Whole Foods, selling items like Amazon Echo inside Whole Foods stores. It’s easy to picture what else Walmart would do with Barnes & Noble: fill in the gaps with non-book items from Walmart stores, use the Barnes & Noble stores as testing grounds to gauge which few books to place in the checkout aisle in Walmart stores, and so on.

Buying Barnes & Noble would even help Walmart in its red-hot war with Amazon for retail dominance, in which Walmart is rapidly expanding its digital business and Amazon, in turn, is dipping its toes into brick-and-mortar. Don’t forget that Barnes & Noble isn’t strictly a brick-and-mortar business: it has an e-reader, Nook. Imagine Walmart buying Barnes & Noble and adopting the Nook as the Walmart e-reader, selling it in Walmart stores.

Moreover, “If someone did buy Barnes & Noble they could renegotiate e-book rights deals with publishers to more aggressively compete with Amazon,” theorized Nate Hoffelder, editor of the e-book news blog The Digital Reader. But he still believes saving the chain “would require a Hail Mary pass.”

To be sure, Walmart may not be interested anymore, if it believes Barnes & Noble is beyond saving. Asked what Barnes & Noble has done wisely to have survived this long, Hoffelder answers, “I can’t really think of anything it’s done wisely, it just hasn’t died yet.”

Barnes & Noble could find a private equity buyer, who would swiftly cut costs and look for efficiencies. Or an upscale food chain like Starbucks could buy it and turn the stores into book cafés, which many of them already feel like.

—

Daniel Roberts covers technology and media at Yahoo Finance.

Read more:

Amazon’s NYC physical bookstore is not really about selling books

Amazon could eventually face antitrust scrutiny as it gobbles up companies

Why Amazon will have certain success selling workout clothes