The biggest busts from the world's most renowned gadget show

CES, formerly known as the Consumer Electronics Show, is the stage that saw the debut of new technologies like the DVD and HDTV. But it’s also often the Island of Misfit Toys.

Companies that put too much faith in marketing research, a CEO’s vision or assurances from stressed-out engineers and developers, use the Las Vegas spotlight to introduce products that should have stayed in the lab. Some meet meet their fate in the consumer marketplace; some don’t even get that far.

But on reflection, these misbegotten gadgets at the Consumer Technology Association’s annual convention also have some lessons for the electronics industry, and for the customers who keep it in business.

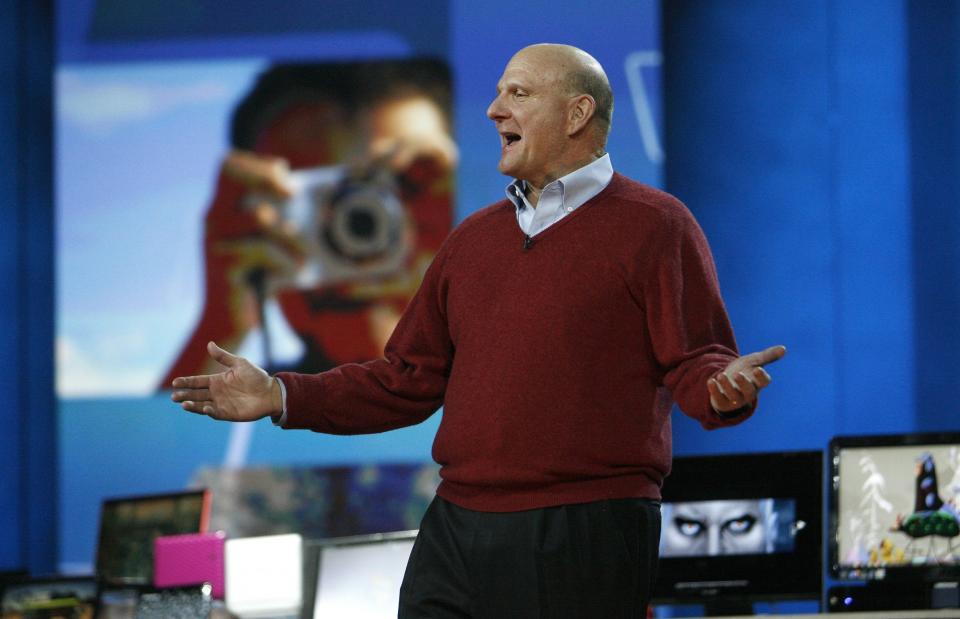

Microsoft-keynote debuts

The company that for years was the biggest name in computing had a lock on CES’s biggest stage: its opening-night keynote. But for many Microsoft (MSFT) concepts, that was not an auspicious launchpad.

In 1998, Microsoft launched its Auto PC platform but then failed to get any US-market vehicles rolling off assembly lines with Windows CE computers in their dashboards. In 2002, its Smart Displays — touchscreen devices you’d use to access your PC’s apps from around the home — proved to be an expensive, sluggish mess. And in 2003, clunky “SPOT” semi-smart watches that plucked updates off broadcasts on FM frequencies drew few takers, leading the company to wind down the project in 2008.

Microsoft’s 2010 keynote may have been the worst of all: It was delayed by a series of electrical problems, and the “Slate” touchscreen Windows 7 computers featured in this presentation never shipped and went unmentioned at the 2011 keynote.

The lesson of this at a time when we do wear computers on our wrists, carry tablets around the house and rely on apps for navigation and entertainment behind the wheel: Having the right ambitions and the right corporate backing won’t help if you’re years ahead of what technology allows.

3D TV

At CES 2010, the problem wasn’t that a single tech company took a misguided leap into the future. Almost the entire TV industry lined up behind 3D TV in the sure hope that people who had flocked to movie theaters to watch “Avatar” in 3D would pay extra to bring that experience home.

Set vendors treated CES attendees to clips from that sci-fi blockbuster as well as a variety of other highlight reels, but nobody brought more starpower to the 3D project than Sony (SNE) — it had Taylor Swift play a brief set at its press conference, which we could watch live in 3D on a screen behind the stage.

But the whole 3D idea was not so … swift. Sorry. The steep cost of the sets, the need to buy separate battery-powered glasses for every viewer, and a lack of 3D fare on cable and satellite doomed the venture. It’s not the first time the electronics industry has made the mistake of trying to take a videophile technology mainstream. And to be fair, often it succeeds, though mostly because the tech in question gets cheap enough to become a standard feature.

Come to think of it, that’s probably explains why my Blu-ray player can play 3D movies.

Non-Amazon e-book readers, non-Apple tablets

The same year 3D TVs came out, gadget vendors lined up to claim a share of the e-book reader business. Established firms like Samsung and newer rivals like iRiver and Plastic Logic showed off e-ink devices that offered many of the same virtues as Amazon’s (AMZN) Kindle, just not the retailer’s enormous content library.

That shortfall turned out to be a problem.

Weeks later, Apple (AAPL) introduced the iPad, which quickly crushed non-Amazon e-book readers into cybernetic splinters. Then a year later, a similar bout of wishful marketing led to such doomed attempts to challenge the iPad as the BlackBerry PlayBook and the Motorola Xoom. Not long after that, the phrase “iPad killer” went out of style.

The Apple of 2016 doesn’t seem as unstoppable as the company we knew in 2010 and 2011, but the point still stands about this perennial CES absentee: If you come at Apple, you’d best not miss.

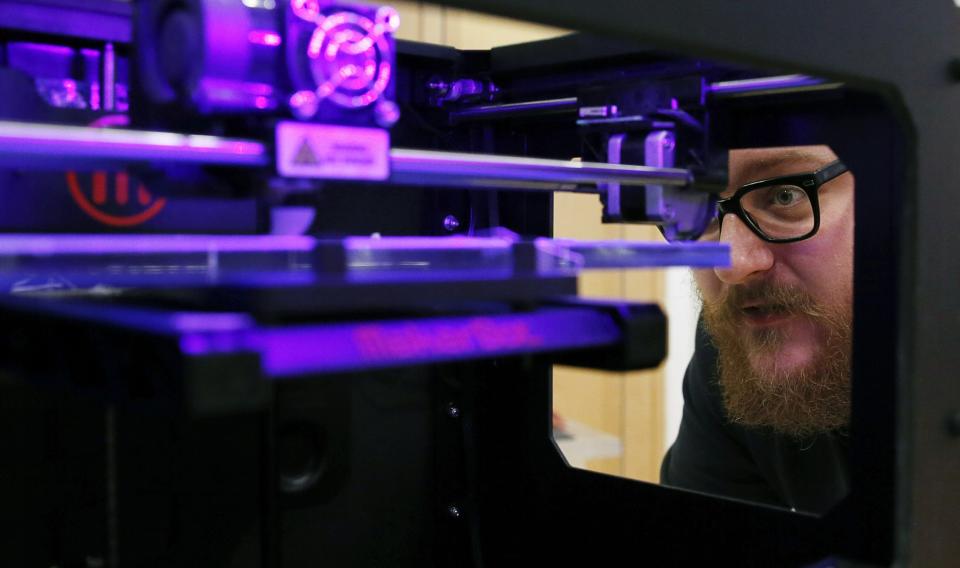

Home 3D printers

3D printers have become a staple of CES coverage — they look neat in photos and so does their output. But they’re not cheap, and most people just wouldn’t use them often enough to keep one around the house; if a public library or a nearby shop has one you can use, that’s enough.

So ambitious CES displays by the likes of Makerbot — Andrew Zaleski’s recap at Backhannel is worth reading to see where that company went wrong — have yet to lead to these things showing up on in too many homes. Sales have been good, even if the Consumer Technology Association recently had to trim its forecast for US shipments in 2016 from 179,000 units to 171,000. But individual customers don’t seem to be doing the buying.

As a Gartner report concluded in October: “The primary market driver for consumer 3D printers costing under $2,500 is the acquisition of low-cost devices by educational institutions and enterprise engineering, marketing and creative departments.” The consumer market is its own creature, and woe to CES exhibitors who forget that.

Palm Pre

Palm drew pleasantly-surprised applause when it introduced this elegant little smartphone in 2009—finally, it seemed, Apple and Google (GOOG, GOOGL) would get some honest competition. But the Pre launched only with Sprint, and then Palm compounded its problems by taking too long to introduce updated models.

The company’s work on the Pre’s webOS software was not in vain, though: Some of its better ideas, such as letting you switch among open apps in a deck-of-cards interface, made their way to Android and iOS, and webOS itself survives as the software running LG’s smart TVs.

The lesson here: Wishing that somebody would inject some choice into a market — you know, like I just did a few days ago when I hoped that Google could make a better smartwatch this year — doesn’t make it so.

More from Rob:

Email Rob at [email protected]; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.