Clinton and Trump are debating about the economy like it's 1996

If the third presidential debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump took place in 1996, you’d scarcely notice the economy they were talking about was 20 years in the future.

There was no discussion of the digital economy when Trump and Clinton met in Las Vegas to spar for one final time before voters hit the polls on Nov. 8. Nothing about automation or workers becoming obsolete. The only reference to the internet involved Clinton’s ever-elusive emails. Clinton made one vague reference to “high-tech manufacturing,” a comment that could have come any time during the last 30 years. Other than that, you’d think the US economy was still dominated by smokestacks and jackhammers.

Clinton wants to tax the wealthy and use the proceeds to fund thousands of new jobs building roads and bridges, as Democratic politicians have sought to do for decades. Republican Donald Trump wants to tear up trade deals that have made the US economy more efficient than ever and forced down the prices of many everyday products.

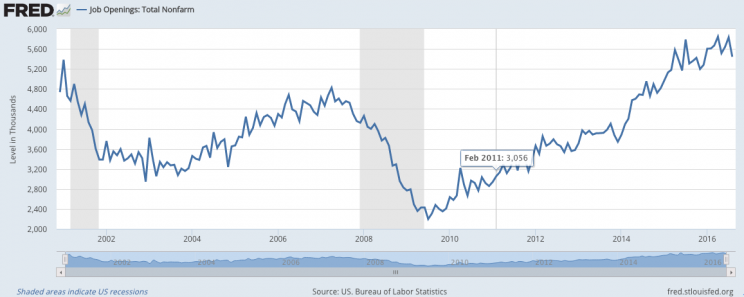

Some inconvenient facts undermine these backward-looking prescriptions for sluggish economic growth. First, there is no shortage of jobs in America today. Employers report 5.4 million openings at the moment, nearly the highest number in the 14 years the government has been tracking such data:

At the same time, the number of working-age adults who either have a job or are looking for one is at the lowest level since 1978. That tells us there are a lot of jobs that people either don’t want or aren’t qualified for. People aren’t looking for work, even though it’s there.

Manufacturing isn’t nearly the problem Trump claims it is. Real manufacturing output, adjusted for inflation, is just about back to the peak reached in 2008, before the latest recession. And it’s 85% higher than in 1988, the last year of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, which some consider a time of peak prosperity. Manufacturing employment, however, has been plunging since 1998. So the work is there, but the workers aren’t. Here’s the data:

Manufacturing is not a sector of the economy that’s been decimated by outsourcing, as Trump repeatedly insists. It’s more like a sector that has been transformed by automation, with software and machines replacing human workers, and the jobs that remain increasingly requiring skilled workers able to operate complex machinery and even program it.

“We have skills and jobs that we could be developing right here without bringing other jobs back,” says Cornell University professor John Hausknecht. “We could be investing to help ease some of the labor shortages we already have.”

Trump and Clinton don’t see it that way. Their plans are very different, but each would involve huge costs that are arguably unnecessary, and almost certainly more than we can afford. The centerpiece of Trump’s plan is a whole new set of trade deals and regulations meant to discourage cheap imports to the United States, in theory encouraging more US manufacturing. That would boost prices on many everyday goods and force may big companies to revamp their supply chains and the way they move goods around the world. If Trump’s plan ever helped create jobs, it would probably come only after an economic slowdown and perhaps a recession caused by the massive displacement of corporate resources.

The cost of Clinton’s infrastructure plan is in dollars—up to $300 billion, which she’d raise by hiking taxes on the wealthy and on financial institutions. Stimulus programs are most effective when unemployment is high and there are a lot of available workers. That’s not the situation now. The unemployment rate is a low 5%, with shortages of construction workers in cities such as San Francisco and Portland. If stimulus spending draws workers out of other fields where they’re already employed, it can depress growth and cause other distortions.

What would be better? There are a lot of ideas for channeling workers into the jobs that exist, rather than tearing up the economy we have and trying to repurpose the jobs of the past.

“The next president can create a tremendous number of digital-economy jobs and enable people to have skills to thrive in them,” says Zo? Baird, CEO of the nonprofit Markle Foundation. “We need rapid low-cost training that gets people the education they need, and helps them update skills throughout their careers.”

The gap between available jobs and available workers largely involves so-called middle skills, the kind that require some specialized training but not a college degree. Assembly-line jobs used to fit the profile, but manufacturers don’t rely on workers turning wrenches the way they used to. They do, however, need workers who can operate and service robots and other sophisticated machines, use 3-D printers, or apply information-technology skills in traditionally non-digital fields such as retail and health care.

A big problem many workers face is knowing what employers are looking for in the first place, since technology changes quickly. Surveys suggest many displaced workers would get retrained, except they don’t know what to get retrained for. The jobs of the future aren’t always in the same place as the disappearing jobs of the past, and some people are reluctant to move, if they even know where they ought to move to. Companies themselves often do a bad job of explaining what kinds of middle-skill workers they’re looking for, posting requirements by degree or certification instead of identifying an actual skill they need. And many companies have cut back sharply on the training they pay for themselves, expecting job applicants to show up pre-trained.

An economic plan focused on the jobs of the future might target new ways to help job seekers find positions that are already open, whether through new training, relocation assistance, or just reliable information on today’s hottest skills. The key to that isn’t a series of trade wars or an improbable tax hike needed to raise revenue—it’s up-to-date information that would let more people make pragmatic decisions.

The stock markets process billions of pieces of data every second in order to provide accurate real-time pricing of securities based on supply, demand and other factors. “Data on jobs is not collected the way stock market data is,” says Baird.

Could it be? Could the government do it? The candidates ought to give it a try. Neither has.

Trump was born in 1946, Clinton in 1947. There’s nothing inherently wrong with a candidate’s age, provided he or she remains plugged into the cultural zeitgeist and capable of learning what people two generations younger know. Neither Clinton nor Trump, however, seems interested in learning about the digital economy that will dominate the lives of their grandkids. Instead, their outdated message seems to be: grab a hardhat.

Rick Newman is the author of four books, including “Rebounders: How Winners Pivot from Setback to Success.” Follow him on Twitter: @rickjnewman.