Congress may have accidentally freed nearly all banks from the Volcker Rule

A few double negatives buried in legislative text may have inadvertently freed nearly all U.S. banks from a regulation known as the Volcker Rule, which sought to curb risky behavior in response to the 2008 financial crisis.

The text in question comes from a package bill passed in May that pared back portions of the Dodd-Frank post-crisis financial regulatory framework. One of the many provisions of the bill offered an exemption from the Volcker Rule to smaller community banks that policymakers felt were burdened by the regulation, which limited banks’ proprietary trading, or trading for their own accounts.

But sources tell Yahoo Finance that some of the largest U.S. banks are now thinking about challenging the interpretation of that May legislation in court, arguing that the bill could be read as also extending regulatory relief to banks far above $10 billion in assets.

If they succeed, this alternative interpretation could free nearly all U.S. banks from a heavily scrutinized post-crisis regulation that some see as an important safeguard against excessive risk-taking but one that opponents criticize as poorly designed and unduly burdensome.

‘And’ or ‘Or’

In the spring of 2018, a number of moderate Senate Democrats teamed up with Senate Banking Committee Chair Mike Crapo (R-Idaho) and the Republican majority to pass a package bill paring back portions of Dodd-Frank, arguing that some of the rules placed an undue burden on smaller financial institutions.

One of those provisions exempted smaller banks from the Volcker Rule. A summary of the bill promises “community bank relief” to banking entities that have “(1) less than $10 billion in total consolidated assets, and (2) total trading assets and trading liabilities that are not more than five percent of total consolidated assets.”

That would already exempt about 97% of the 5,473 U.S. banks and thrifts from the Volcker rule, S&P Global Market Intelligence reported in March.

The summary appears to communicate that a bank needs to meet both standards in order to get the exemption, but some larger banks are focused on a number of double negatives in the fully amended text that could cloud its interpretation.

Doug Landy, a partner at Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy who formerly worked as a lawyer at the New York Fed, told Yahoo Finance that the negatives could be interpreted as flipping the “and” in the statute to an “or.”

Under the “or” interpretation, an institution would in theory only need to meet one of those standards to get an exemption, meaning that banks above $10 billion could still be freed from the regulation as long as their trading assets and liabilities are below 5% of their total assets.

“I think the language in the provision is confusing. It’s a double negative and if you add in the prior negative that says the term ‘insured depository institution,’ it really is a triple negative,” Landy said. “That makes it hard to interpret, which leaves the power of interpretation to the agencies.”

Three sources confirmed to Yahoo Finance that a former bank regulator — Keith Noreika, appointed by the Trump administration to serve as acting Comptroller of the Currency from May to November 2017 — is now advising banks to look into the “or” interpretation and floating the idea of taking the issue to court.

Noreika, now a bank attorney at Simpson Thacher, did not respond to requests for comment.

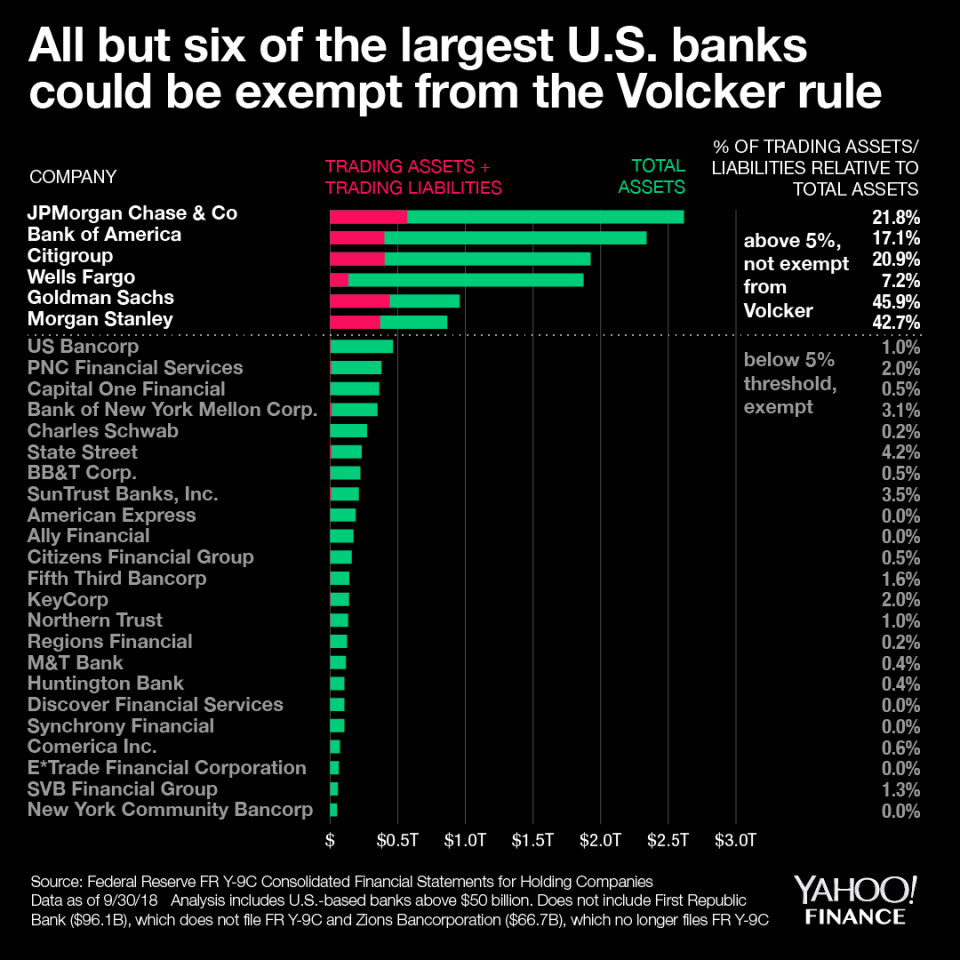

The regulators have yet to clarify exactly what constitutes “trading assets and trading liabilities” — a clarification could come in a separate rulemaking — but a Yahoo Finance analysis of regulatory data on trading assets and liabilities estimates that nearly all U.S. banks above $50 billion would be free from the Volcker Rule under the “or” interpretation. The six largest banks — JPMorgan Chase (JPM), Bank of America (BAC), Citigroup (C), Wells Fargo (WFC), Goldman Sachs (GS), and Morgan Stanley (MS) — would all still be subject to the regulation because they have sizable holdings of trading assets and liabilities, meaning they meet neither condition for the Volcker exemption.

The five government agencies with jurisdiction over the Volcker rule — the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, and the Securities and Exchange Commission — either declined to comment for the story or did not respond to requests for comment. But early indication from the regulators is that they sympathize with the tighter interpretation of the statute.

A notice of proposed rulemaking on the Volcker Rule notes that the OCC is reading the statute as offering exemption to banks “with total consolidated assets of $10 billion or less … if their trading assets and trading liabilities do not exceed 5 percent of their total consolidated assets,” implying a need for both criteria to be met.

Oliver Ireland, former associate general counsel at the Fed, said he does not see the statute as having a “mistake or a loophole.” But Ireland, now senior counsel at Morrison & Foerster, said that if a bank were to take the statute’s interpretation to court, the legal question would concern the power of the regulatory agencies to interpret ambiguous language, a test known as the “Chevron deference.”

The largest banks that could benefit from the alternative interpretation are U.S. Bancorp (USB) and PNC Financial Services (PNC), both of which declined to comment for this article.

Congress could move to tighten the language through a technical corrections bill. But the Crapo bill’s drafters insist there’s no issue to begin with.

“Plain reading of the statute makes it pretty clear the cap is $10 billion,” a spokesperson for North Dakota Senator Heidi Heitkamp — one of the Democrats who helped broker the bill — told Yahoo Finance. “Both Republicans and Democrats agree on that.”

“We’re going to have to have a lawyer, officer, doctor”

The Volcker Rule has been plagued with legal ambiguity since its inception.

Former Fed Chairman Paul Volcker had a fairly simple idea: curb excessive risk-taking by discouraging banks from engaging in activity designed to juice their corporate profits instead of helping clients and customers grow their money. The rule limits banks from using their accounts to do short-term proprietary trading of securities, derivatives, and commodities. The rule also limits banks from running hedge funds or private equity funds.

In practice, the rule was extremely difficult to implement. Even though it was signed into law in 2010, it took regulators five years to finalize and apply the regulations.

The sluggishness to enact the rule was partly due to the complexity in applying the prohibition; in addition to a maze of exemptions around specific types of activities, the Volcker Rule also included vague definitions of what qualified as “proprietary trading” and what types of “covered funds” banks are allowed to operate.

JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon famously bashed the rule in 2012 for its complexity, joking that the company would need “a lawyer, officer, doctor — to see what their testosterone levels are” in order to comply with the regulation.

The Fed’s current head of supervisory matters, Randal Quarles, said in March that the central bank is interested in revisiting the rule. His biggest criticism: the Volcker Rule is just too complex and hard to understand.

“The statute…rests on a number of complex requirements that are difficult or impossible to verify objectively in real life,” Quarles said.

This double negative issue could entangle the Volcker Rule in a whole new layer of complexity, one that might take months — if not years — in the courts to resolve.

Brian Cheung is a reporter covering the banking industry and the intersection of finance and policy for Yahoo Finance. You can follow him on Twitter @bcheungz.

Read more:

NY Fed’s Williams: There’s still room for ‘further gradual’ rate increases

FDIC chair: We need to be preparing for the next downturn

Atlanta Fed’s Bostic joins chorus of concern over leveraged lending

Fed’s Clarida: Central bank still looking for ‘ultimate destination’

There’s a 30% chance of a recession in 2020, Morgan Stanley says