Consumers and GDP — What you need to know for the week ahead

After a lot of talk and no healthcare deal, markets this week will turn their attention back to economic data and the rest of the Trump agenda.

On Tuesday, stocks had their worst day of the year with bank stocks — a standout since the election — bearing the brunt of the selling. Treasuries, particularly at the long end of the curve, also continued their recent rally.

Take these together, and along with concerns over healthcare, questions about whether the “Trump trade” was already falling apart abounded.

This led some analysts, including Jonathan Golub at RBC Capital Markets, to note that for all of the talk about whether Donald Trump’s economic agenda is powering stock markets higher, there’s a positive global earnings and growth story markets are also reacting to.

And while questions over what is or is not powering stocks higher may continue, there is little doubt that business and consumer sentiment has been positively impacted by Trump’s election win.

This week, we’ll get two checks on consumer sentiment, with The Conference Board’s reading due out on Tuesday morning and the University of Michigan’s final check on confidence for March due out Friday.

Elsewhere on the economic calendar, a final reading on fourth quarter GDP is due out Thursday morning, and on Tuesday we’ll get an update on home prices in the U.S.

Economic calendar

Monday: Dallas Fed manufacturing, March (22 expected; 24.5 previously)

Tuesday: S&P Case-Shiller home price index, January (+0.7% expected; +0.93% previously); Conference Board consumer confidence, March (113.7 expected; 114.8 previously); Richmond Fed manufacturing index, March (15 expected; 17 previously)

Wednesday: Pending home sales, February (+2% expected; -2.8% previously)

Thursday: Fourth quarter GDP, third estimate (+2% expected; +1.9% previously); Fourth quarter personal consumption, third estimate (+3.1% expected; +3% previously); Initial jobless claims (245,000 expected; 261,000 previously)

Friday: Personal income, February (+0.4% expected; +0.4% previously); Personal spending, February (+0.2% expected; +0.2% previously); Core PCE, February (+1.7% expected; +1.7% previously); Chicago PMI, March (57.0 expected; 57.4 previously); University of Michigan consumer sentiment, March (97.6 expected; 97.6 previously)

The shrinking stock market

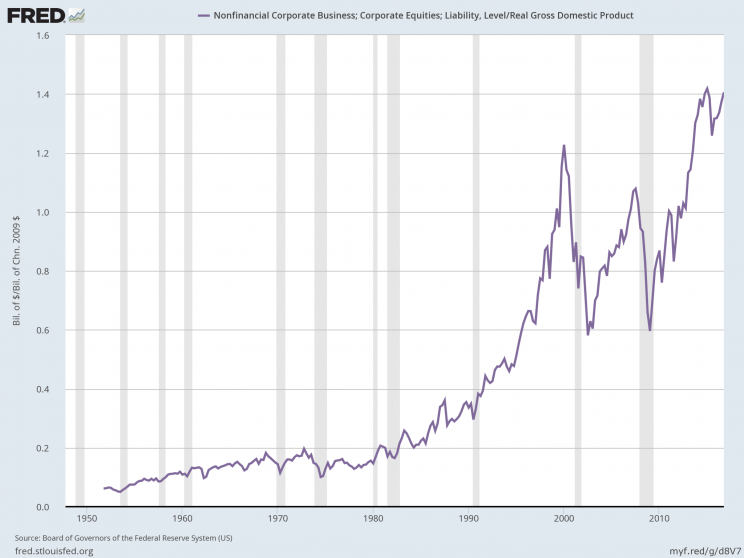

Over the last several decades, the U.S. stock market has accounted for a rapidly increasing percentage of GDP.

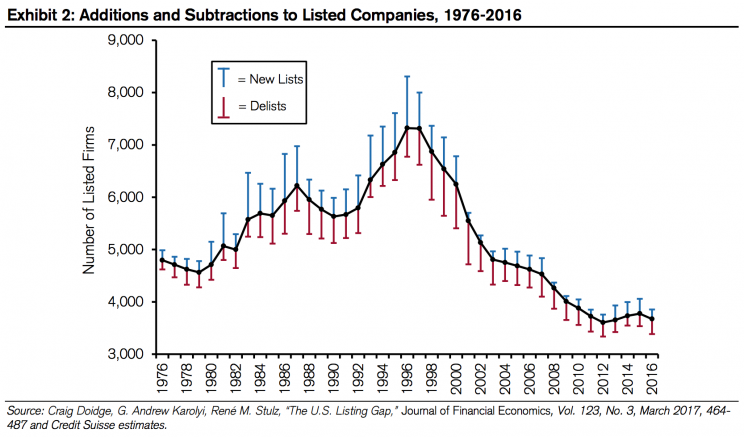

And over this same period, the number of stocks in the market has been on a steady decline. In the Wilshire 5000, for example, there are now just 3,816 members.

In a paper published this week, Michael Mauboussin and his team at Credit Suisse examined this phenomenon and whether this speaks to a concern about the health of U.S. markets or a changing environment for business funding.

From a health perspective, there is nothing bad about the number of stocks listed on U.S. markets shrinking. “The companies that are listed on exchanges are bigger, older, and in more concentrated sectors than two decades ago,” Mauboussin writes. “This likely contributes to public markets that are more informationally efficient than ever before.”

The flipside of this is that to be a truly diversified investor, mixing up your market sectors is not going to cut it.

A shrinking number of publicly-listed equities, “changes the nature of an investor’s opportunity set,” Mauboussin writes.

“In 1976, an institutional investor who wanted exposure to U.S. equities had only to buy a diversified portfolio of public companies and a venture capital (VC) fund. In 2016, that investor would have to buy a diversified portfolio of public companies, a private equity fund, and late-stage as well as early-stage venture capital.”

Filling the gap in public market trading activity, then, has been the exchange-traded fund.

Trading like a stock on a public exchange, ETFs offer investors numerous benefits, including daily liquidity and exposure to formerly esoteric strategies.

And as the number of publicly-listed businesses has declined the number of ETFs listed has spiked, as has the amount of trading done via ETFs.

“The most active traders of ETFs are institutional investors that use them to speculate, hedge, and arbitrage,” Mauboussin writes.

“ETFs are just 15 percent of total listings but are more than 30 percent of U.S. trading measured by value and 20 percent by volume. Trading in ETFs is very concentrated. The SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust alone has averaged about 9 percent of the volume on the New York Stock Exchange over the past five years, and 20 ETFs make up about 90 percent of ETF trading volume.

“That ETFs are such a large part of the market likely represents both an opportunity and a risk. The opportunity is to use ETFs as an effective way to hedge or gain quick exposure to the market, a sector, or a factor. The risk is that ETFs may impede price discovery if they become too prominent.” (Emphasis added.)

And so as the number of constituents in the stock market has declined, the pricing of the remaining members has gotten more efficient. This efficiency, however, has made it harder for investors of all sizes to outperform both in the stock market and outside of it.

As a of the stock market’s decline in popularity, asset classes like private equity and venture capital have risen in popularity. But as these asset classes gained popularity amid an increasingly efficient public market environment, so too did returns in these spaces decline.

“Venture capital funds launched in the 1990s outperformed public markets,” Mauboussin writes.

“But funds started since 2000 have underperformed public markets, with an improvement in recent years. Buyout funds with vintage years before 2006 outperformed public markets, but those launched in the last decade have only equaled the returns of the market. Hedge funds have also seen diminishing excess returns in the past decade.”

The overall upshot here is that investing is both as easy and as hard as its ever been.

ETFs and the changing character of the stock market — towards larger, more profitable, and more mature businesses — benefit investors who are seeking low-cost exposure to assets likely to outperform cash and Treasuries over time. Institutional investors looking to hedge riskier, more concentrated bets can now turn to the stock market for this need.

But outperforming your peers, either in the stock market or in spaces like private equity and venture capital, has now become an even more difficult prospect.

—

Myles Udland is a writer at Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter @MylesUdland

Read more from Myles here: