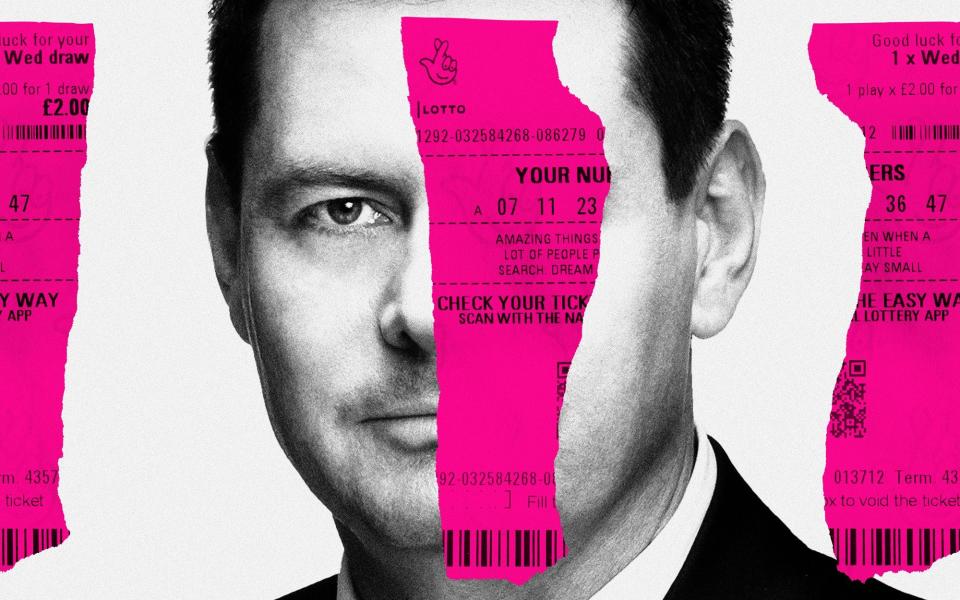

How the Czech billionaire who won the National Lottery is losing the battle to revive it

When an IT meltdown at tech giant Microsoft swept across the world earlier this year, causing havoc at tens of thousands of businesses, it was perhaps inevitable that the National Lottery would be caught up in the chaos.

As airlines, hospitals, banks and supermarkets scrambled to get their systems back online, thousands of Lottery customers reported being unable to access results or buy tickets ahead of the forthcoming Saturday night draw.

The complaints began as the weekend was unfolding with some customers unable to access the National Lottery app as well as the website, with the numbers mounting until late into the following morning, according to Downdetector, a technology outage monitor.

The outage was yet another setback for Allwyn, the Czech lottery giant which has faced a succession of difficulties since it took control of the National Lottery earlier this year with a promise to revitalise the storied national institution and charity mega-donor.

National Lottery’s new operator has faced financial and technological setbacks since taking over the licence in February, as well as continued concerns about its suitability.

The awarding of the licence to Allwyn in March 2022 was supposed to herald an exciting new era for one of Britain’s biggest contributors to charitable causes, and a game played by 10m people in Britain.

Its bid was backed by business luminaries including Sir Keith Mills, known for inventing the Air Miles and Nectar Card loyalty schemes, and Justin King, the former chief executive of Sainsbury’s, who chairs its UK board. The contract is estimated to be worth up to £100bn in sales over its 10-year duration.

Sir Keith stood down from Allwyn’s UK board in January, to be replaced by Lord Coe – another grandee.

Allwyn promised to revamp the Lottery through new games and draws, boosting sales and money for good causes. However, repeated setbacks have emboldened critics who opposed its involvement from the outset.

Performance has been so poor since taking over the licence in February that Allwyn seems almost certain to fall woefully short of its financial projections in the very first year – forecasts that were pivotal in the Gambling Commission choosing Allwyn over rival bidders to operate the National Lottery.

A raft of issues

Before the official handover had even taken place, Allwyn was backpedalling on its commitments with a warning that delays to planned new games could hit the amount of money raised for good causes.

Andria Vidler, who was appointed boss of Allwyn’s UK operations a year ago, declared in January that initiatives such as draw-based games “will bring the magic and enjoyment back”. However, at the same time, Allwyn was forced to concede that the new games will not be brought on stream until this time next year.

The delay comes as Allwyn seeks to change technology providers by ending the Lottery’s association with International Game Technology (IGT), the company that has supplied the software and hardware underpinning shop lottery terminals since the National Lottery was launched in 1994.

An Allwyn insider described the planned move as “one of biggest tech transitions undertaken by a lottery provider anywhere”.

However, an insider at Camelot, which ran the National Lottery before Allwyn, claimed tech experts had likened the move to “trying to stick a Microsoft system on top of an Apple computer”.

Allwyn has blamed the setback on a legal dispute with IGT. The technology company mounted a legal challenge to Allwyn’s actions that was dismissed in the High Court in 2023, but the company continued to pursue Allwyn for damages until January of this year.

A raft of other issues have occurred. Customers have faced long delays in receiving their winnings; trouble with the system that automatically replenishes scratch cards at newsagents has left some retailers with empty dispensers; and more than 700 Post Offices across the UK have said they will no longer sell tickets and scratchcards.

The arrival of new National Lottery terminals to all 40,000 partnered stores has been delayed by “at least half a year”, Robert Chvátal, Allwyn group chief executive, admitted last October. Insiders insist the rollout will begin “shortly”.

Meanwhile, discussions about cutting the price of a Lotto ticket from £2 to £1 have gone nowhere so far, several years after they were first revealed.

‘An absurd amount of money’

Those involved in the bidding process believe that Allwyn promised to deliver between £10.4bn and £10.5bn turnover in the first year, and a Financial Times report has described it as a contract “projected to generate sales of around £10bn a year”. During its final year under Camelot, the National Lottery generated revenue of £8.2bn.

However, recent issues have made it difficult to see how Allwyn will reach its promised revenue targets.

It has also been reported that the Gambling Commission cut the estimated value of Allwyn’s 10-year licence – an estimate intrinsically linked to revenue – to between £7.9bn and £7.8bn “based on updated estimates of sales forecasts”.

A Gambling Commission spokesman said: “We do not recognise the figures you have provided as accurate. However, it is right that commercial forecasts are kept under review and updated in light of unforeseen variables. Any projection changes will always be examined by the Commission to ensure they are compatible with Allwyn’s application.”

Critics say Allwyn’s forecasts were unrealistic from the start, partly because it was so desperate to wrestle the licence from Camelot in the first place. It has promised to more than double the amount that Camelot had raised for good causes over the course of the licence, from £17.9bn to £38bn, a figure that former senior Camelot figures scoff at.

“They won by basically promising an absurd amount of money. We could not see any possible way you could ever raise that sort of money in any way whatsoever,” said one ex-Camelot executive.

The Gambling Commission said: “Over the next 10 years the Fourth [National Lottery] Licence will lead to an increase in returns to good causes whilst keeping the National Lottery safe to play. Allwyn has committed to investment that is expected to deliver growth and innovation.”

Links to the Kremlin

The Gambling Commission’s decision to hand one of the largest public sector contracts of all-time to Allwyn triggered immediate scrutiny of the business ties that Karel Komárek, Allwyn’s Czech billionaire owner, had with the Kremlin.

Though those links have since been severed, Komárek’s holding company, KKCG, was still in business with the Kremlin-owned gas company Gazprom in the Czech Republic region of Moravia both at the time it was awarded the licence, and when it formally obtained it this February.

In June, KKCG finally squeezed Gazprom out of the venture - two years after the gambling Commission told MPs on the culture, media and sport select committee that an announcement about plans to end the Gazprom relationship was anticipated within “days”

A spokesman for Allwyn said: “Neither KKCG, its subsidiaries, nor its founder have any ties to Russia. Immediately following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, KKCG subsidiary MND… worked to end its joint venture with Gazprom Export (GPE) in Moravia Gas Storage (MGS). MND successfully delivered on this.”

‘Seriously flawed’ licence process

The choice of Allwyn also provoked legal acrimony, following a bitter three-way bidding war between Allwyn, the media tycoon Richard Desmond and Camelot, the holder of every licence since weekly draws began in 1994.

Desmond’s Northern & Shell group filed a procurement lawsuit against the Gambling Commission in February over the decision, and at a High Court hearing in June it branded the process “seriously flawed”, accusing the Commission of providing “unfairly favourable treatment to Allwyn”.

Separate legal action brought by Camelot ended when Allwyn took it over in a £120m deal. Former Camelot figures claim the Gambling Commission was determined to strip it of the contract. Camelot had been reprimanded years earlier after profits rose faster than returns to good causes and insiders claim relations never fully recovered.

Criticism of the bidding process persists. Rival bidders have raised questions about the independence of Rothschild, the Gambling Commission’s chief adviser, after it emerged that the investment bank had recently acted as counsel to Allwyn on its takeover of OPAP, the Greek betting firm.

“We remain resolute that we have run a fair and robust competition, and that our evaluation has been carried out fairly and lawfully in accordance with our statutory duties,” the Gambling Commission said. Rothschild declined to comment.

MP’s have also expressed doubts about Allwyn’s suitability. Sir Iain Duncan Smith, vice-chairman of the all-party parliamentary group (APPG) on gambling-related harm, said the APPG had been “astounded that the Gambling Commission awarded the Lottery contract to Alwyn”.

Sir Iain said: “Given the many subsequent issues that have emerged since Allwyn took over the operation of the contract and its management company, the Commission should scrutinise their original decision and the issues that have emerged since the contract was awarded.”

‘Eager to ingratiate’

It is not the first time Allwyn’s lottery practices have come under scrutiny. Greece’s gambling regulator last year handed down a €24.5m (£20.5m) fine against OPAP over breaches of competition laws.

The Hellenic Gaming Commission found that OPAP, which is owned by Allwyn, had abused its dominant market position through the use of non-compete and exclusivity clauses. The Greek company said it “strongly disagreed” with the decision, labelling it “baseless”.

Suggestions that Allwyn is experiencing anything more than teething problems are batted away by representatives: “Allwyn has invested more than £300m into the essential modernisation of the National Lottery, which is held back by technology dating back to 2009 before iPads or Instagram.”

A spokesman continued: “We have made this investment despite over two years of near continuous and disruptive legal actions, brought by parties disappointed by the outcome of the Fourth National Lottery Licence competition. We remain committed to our objective to double weekly contributions to good causes by the end of the 10-year licence.”

Allwyn remains eager to ingratiate themselves with the establishment through extensive lobbying and expensive marketing. It is a marquee sponsor of the annual garden party for the Spectator magazine – a soiree attended by a “who’s who” of political and media circles – and the Society of Editors’ “Media Freedom” awards.

It also lent its name to a three-day event at last month’s Labour Party conference in Liverpool where attendees were invited to debate the future of the creative and cultural industries. Speakers included Les Dennis of Family Fortunes fame and actor Andy Serkis, best known for playing Gollum in the Lord of the Rings franchise.

The battle to take over the National Lottery was hard-won for Allwyn. Proving it can hit the jackpot may be tougher.