Dan Loeb's Nestle stake brings attention to the evolving packaged food business

The packaged food industry is being forced to make big changes with the evolving world economy. Many big brands have invested in major adjustments to stay competitive. Meanwhile, companies that aren’t changing fast enough are having to answer to activist investors.

Dan Loeb and his hedge fund Third Point just announced a new $3.5 billion stake in Nestle SA. In a letter to investors on Sunday, Loeb specifically pointed to Nestle’s inability to adjust to a “lower growth world.” In other words, the Nestle business model hasn’t adjusted for a lower growth reality for the sector, something peers have wised up to.

Nestle is $260 billion business which makes it the largest food company in the world. It has its hands in everything from candy and infant formula to coffee, pet food and bottled water.

“While its peers have adapted to this lower growth world, Nestlé has remained stuck in its old ways,” Loeb wrote in in the letter. “While Nestlé has stood still, its peers have pursued productivity increases aggressively and made other changes in order to deliver earnings growth and create shareholder value in a slower sales growth world.”

The “Nestle model” of 5% to 6% annual organic sales growth and margin improvement is no more, explained Loeb, which could threaten future dividend growth for shareholders.

In fact, his four focuses for the company—productivity improvement, returning capital to shareholders, portfolio reshaping and monetizing units (specifically L’Oreal for Nestle)—speak to the current playbook in the food industry.

Shrinking shelf space and new forms of competition

Organic sales growth for leading CPG companies have disappointed in recent years. In fact, Goldman Sachs’ Jason English pointed out in a recent note that the US packaged food group he covers set a new all-time low in organic sales, declining 1.6% in the first quarter. And, as shown in the chart below, sales have been tepid over the last few years, with a marked slowdown this year.

Overall category demand growth has slowed particularly for center-store categories, as opposed to peripheral categories where you typically find fresh foods. According to English, center-store is where once-loved grocers like Whole Foods (WFM)—now being acquired by Amazon (AMZN)—are struggling to get items off the shelves in a way that generates strong returns. This is exacerbated by competition from new entrants, as the barriers to distribution are falling, English said.

“Shifts in the retail environment pose risks broadly for center-store processed food manufacturers,” according to Piper Jaffray’s Michael Lavery. “We expect continued downward pressure on pricing from intense retail competition… We also expect ongoing volume pressure, driven by continued shifts in consumer preferences and potentially exacerbated by shrinking shelf space and growing competition from prepared foods and meal kit delivery services.”

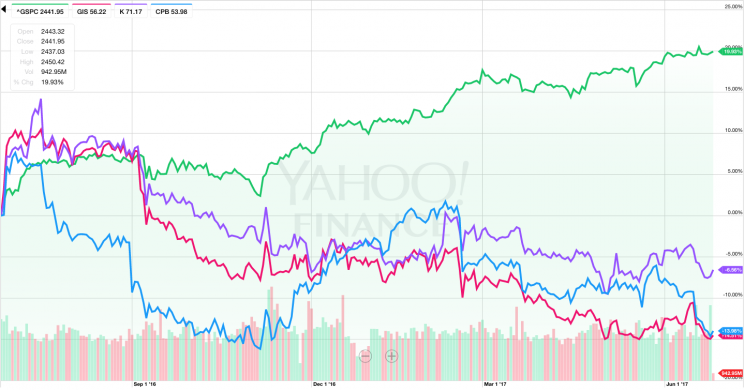

Packaged food names like General Mills (GIS), Kellogg (K) and Campbell Soup (CPB), have well underperformed the market in the last year, as shown in the chart below (the S&P, in green, is up 20% while those three names are in negative territory).

And activists have been keen on this trend. In August 2015, Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square took a $5.5 billion stake in snack-maker Mondelez (MDLZ), pushing for cost cuts, revenue growth and an eventual sale. Sound familiar?

Meanwhile, names in the sector have worked to reformulate their models, a point Loeb highlighted in his letter. Amid slowing sales, food names have restructured their portfolios in order to bring out value.

Splits, spin-offs, mergers, restructurings

Mondelez itself was a product of that pressure. In 2011, after being pressured by Nelson Peltz’s Trian fund, Kraft split into the domestic Kraft with brands like Jell-O and Velveeta and the international Mondelez with emerging markets snack brands like Oreos and Ritz crackers. Prior to Kraft’s announcement of a split the company had barely moved for a decade. The new units, meanwhile, have reached for growth. The March 2015 announcement that Kraft would merge with Heinz, in a deal backed by Berkshire Hathaway and 3G Capital, marked the last piece of a long series of breakups for the food manufacturer. (And Kraft Heinz recently bid for Unilever, albeit unsuccessfully.)

Sara Lee, which was mentioned in Loeb’s letter, split in 2012 after years of losing market share, into its packaged meats business, Hillshire Brands, and an international coffee company, D.E Master Blenders (which was later bought by a European conglomerate). Hillshire got not one, but two bids—from Pilgrim’s Pride (PPC) and the ultimate winner Tyson Foods (TSN), which paid a 70% premium for it in 2014.

Milk company Dean Foods (DF) spun off WhiteWave Food, its soy and almond milk segment, in 2013. WhiteWave, which posted strong growth, was then acquired by Danone for $10 billion in a transaction completed earlier this year.

Conagra (CAG) has also been struggling to reinvent itself after selling its private label business for $2.7 billion in 2016 to focus on its branded business, including reportedly a failed bid for Pinnacle Foods (PF).

Other giants have been pressured to break up, including Pepsi (PEP). Nelson Peltz’s Trian advocated for a complete separation of the giant’s snacks and beverage business as well as potential merger with Mondelez, where he is a board member. Peltz ultimately exited the position after strong stock performance.

The bottom line: The status quo isn’t working in this industry and companies are divesting and recombining in the search for growth.

—

Nicole Sinclair is markets correspondent at Yahoo Finance

Please also see:

On Amazon buying Whole Foods: ‘The ramifications for all of retail are seismic’

This may be ‘as good as it gets’ for earnings growth, BofA analyst says

Economist warns: ‘Once again, the Fed’s credibility is on the line’