Data and tracking are key to brick and mortar’s comeback

It’s not a secret that you are tracked every time you step your virtual feet onto the internet. The ad you keep seeing for that pair of boots you looked at on Zappos three weeks ago is not there by coincidence — it’s there because of cookies and a host of other new-fangled ad tech.

But what a lot of people don’t realize is that customers are also tracked when they’re shopping in a physical store, thanks to scores of cameras mounted on ceilings and other advanced software. In the 21st century, data is everything.

People have been counting customers since before the internet existed but in the past few years, tech similar to what Amazon has in its grab-and-go stores has allowed retailers to get extremely detailed data on their shoppers, data that they can use to rejigger stores.

RetailNext is one of the companies that provides thousands of brick and mortar stores with tech that allows them to obtain and analyze valuable customer data. While RetailNext does not disclose its clients, the company has publicly acknowledged that its clients include big retailers like Bloomingdales and smaller niche concerns like Chrome Industries, a bicycle apparel and accessories company, and AllBirds, a trendy wool footwear company.

For years, Alexei Agratchev, RetailNext’s CEO has been saying that the “death of brick and mortar” is overstated, and that the traditional sales methods have significant advantages over their online counterparts — especially if they can figure out the data problem and innovate.

“If you look at the Wayback Machine and see what the websites looked like, the shopping experience was very different,” he said. “But if you look at brick and mortar, it hasn’t evolved.”

But that doesn’t mean brick and mortar can’t evolve, or that it should give up its inherent advantages over e-commerce when it comes to the sale of apparel, beauty products, accessories, and food, Agratchev says.

What real life stores can measure

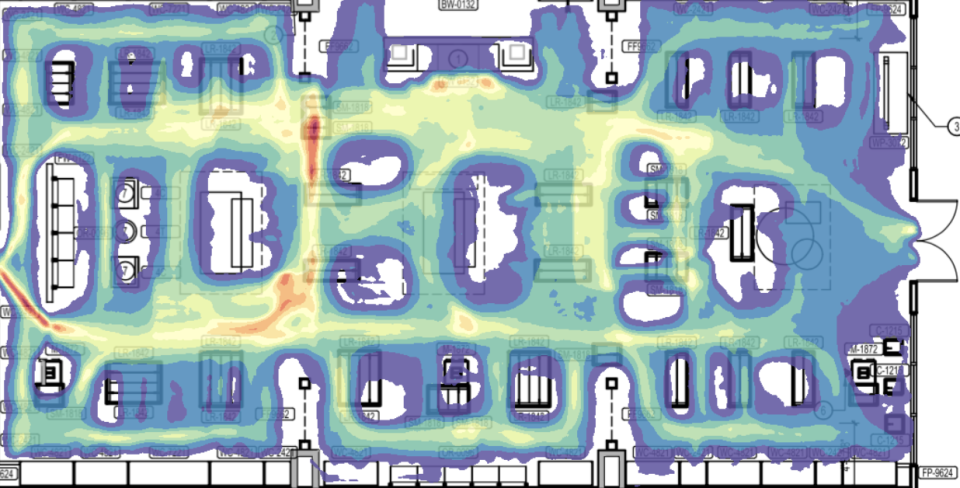

Using cameras mounted to the ceiling, RetailNext is able to track how many people walk by a store, how many people go inside, how many linger in front of the window, and for how long. It can track customers’ in-store behavior: whether they make a sale, and more.

If a store’s conversion rate is bad, and customers are leaving empty handed, it’s easy to see if clothing style, size and fit issues are the problem — lots of changing room visits, but not many sales — or whether the pinch point is at the checkout, one of the most common problems. If a window display isn’t working, the lines are too long, or the store layout is too confusing, stores can easily figure out how to fix it. These tactics can be blended together with other things like leveraging the guest Wi-Fi networks for anonymized data, to determine top searches, potentially showing what products the store didn’t have but should.

Agratchev argues that a physical store is an incredible source of data, if you can extract the data. A person’s movements, expressions, and in-store behavior has almost limitless potential.

For brick and mortar, there is a sense of impeccable timing. What was formerly only possible through consultants and intuition is now attainable in the near future thanks to video and advanced deep learning software that can deliver actionable metrics to businesses at prices that are similar to the aging traffic counters.

“Deep learning AI has a big application on the level of data you can get,” says Agratchev. “You can tell if a customer took a shoe and tried it on. Historically, training a computer to recognize that has been impossible.”

Brick and mortar, but with data

Agratchev says there is a great argument for a brick and mortar resurgence. Online, full price transparency and rising shipping and return expenses have made e-commerce increasingly untenable for some retailers — who aren’t named Amazon.com.

This, Agratchev notes, is why e-commerce companies are increasingly getting into the brick and mortar game. It’s simply more profitable, and they can use online data to help tailor their business.

Store window traffic, it turns out, is not an issue for many businesses, and retooling a window display for free and using a store as a customer acquisition vehicle is often a much better play than traditional ad spending. A better conversion rate is often easier than a bigger reach — and just as effective.

“We notice all these pure play e-commerce guys, they open stores and they’re usually shocked,” says Agratchev. “Your customer acquisition costs, if you have a decent brand in a decent location, are nonexistent.”

Online, the story is more difficult, according to Agratchev e-commerce outfits have a revenue ceiling between $50 million and $200 million without turning to wholesale.

“If you look at the online environment, the variable costs are very high. There’s pricing pressure, customer acquisition costs, delivery costs and expectations,” says Agratchev. “Amazon set these amazing expectations to be able to offer fast delivery and free returns. For every shoe retailer when people try on three pairs and send two back — it’s impossible to make money on that unless your margins are ridiculous. That cost doesn’t go down with scale.”

Brick and mortar acolytes like Agratchev say that service and good employees provide the key to the physical store’s future. “Labor is the biggest opportunity to drive sales profitably,” he says. “I think the checkout experience can be integrated into the shopping experience where you don’t have to stand online and check out separately.”

With freed-up labor and less waiting — think those Amazon grab and go stores — personalization and drastic store improvements are opened up as distinct, almost limitless possibilities. For some, a black slate will be difficult, but for creative companies, it’s an opportunity to revive brick and mortar.

Ethan Wolff-Mann is a senior writer at Yahoo Finance focusing on consumer issues, tech, and personal finance. Follow him on Twitter @ewolffmann.

This story is a part of Yahoo Finance Presents: The Retail Revolution, March 5-9, 2018.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance