Exclusive: What Fitbit's 6 billion nights of sleep data reveals about us

How we sleep is unbelievably important. Getting too little sleep not only makes you feel lousy and cranky, but it’s also linked to obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and even early death. (No pressure.)

But it’s amazingly hard to measure our sleep, as a population. Sure, one person at a time can stay overnight at a sleep lab, hooked up to scalp electrodes — but try sleeping normally that way, away from home and wired to strange equipment. Other sleep studies use self-reporting, where you write down each morning how you slept, but that data is famously unreliable.

Now, though, there’s a new way to study our sleep: Fitness bands, worn by millions of people. Most of Fitibit’s bands, for example, have built-in heart-rate monitors, which produce much more accurate sleep-measurement results than earlier bands. These bands track your sleep automatically, in your own bed, on your normal schedule, under normal conditions.

Since Fitbit began tracking sleep stages in March 2017, it has collected data from 6 billion nights of its customers’ sleep. This is a gold mine — by far the largest set of sleep data ever assembled. (This data is anonymous and averaged; it’s not associated with individual customers’ names.)

“It’s a really, really exciting and really rare data set,” Fitbit data scientist Karla Gleichauf says. “It’s probably the largest biometric data set in the world.”

The measurements include not just how long you sleep, but what stages of sleep you experience. Each morning, the Fitbit app shows which parts of the night you spent in REM sleep (the vivid-dreams stage, good for mood regulation and memory processing), in deep sleep (good for memory, learning, the immune system, and feeling rested), in light sleep, and awake. (It’s always disheartening to see how much of the night you waste in little one- or two-minute wake-ups that you don’t even remember.)

But wait, there’s more. The Fitbit app also knows your gender, age, weight, height, location, and activity level. Therefore, the company’s data scientists can slice and dice its massive sleep database in fantastic ways. They should be able to tell us who sleeps more: men or women. Northerners or Southerners. East Coasters or West Coasters. They should be able to calculate our national average bedtime. They should be able to draw all kinds of conclusions about the way we sleep — and what’s good for us.

Now, for the first time, they have. Gleichauf and her boss, Conor Heneghan, Fitbit’s lead sleep research scientist, agreed to mine that vast sleep database to unearth some of its secrets. Some of their findings reinforce what sleep scientists have already studied; some have never been measured before.

Here’s what Fitbit discovered — a Yahoo Finance exclusive.

Men vs. women

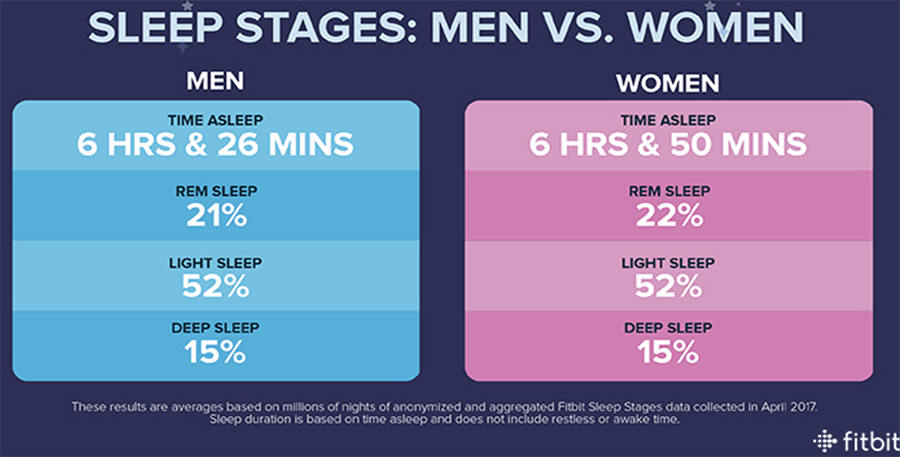

Women sleep 25 minutes longer a night than men. They average six hours and 50 minutes of sleep a night, whereas men get only six hours and 26 minutes. Neither group gets anywhere close to the recommended eight hours a night.

Women also get about 10 minutes more REM sleep than men every night, too — a gap that widens after age 50.

Why these differences? “It’s really not known if it’s a physiology thing, is it a cultural thing, who knows,” Heneghan says. “I think that would be super exciting over the next 10, 20 years for people to really get into why.”

The news for women isn’t all good, though: They’re 40% more likely to suffer from insomnia — trouble falling asleep — than men.

(Those two findings could be related, too: Since women’s sleep is less efficient, they have to spend more time in bed.)

Old vs. young

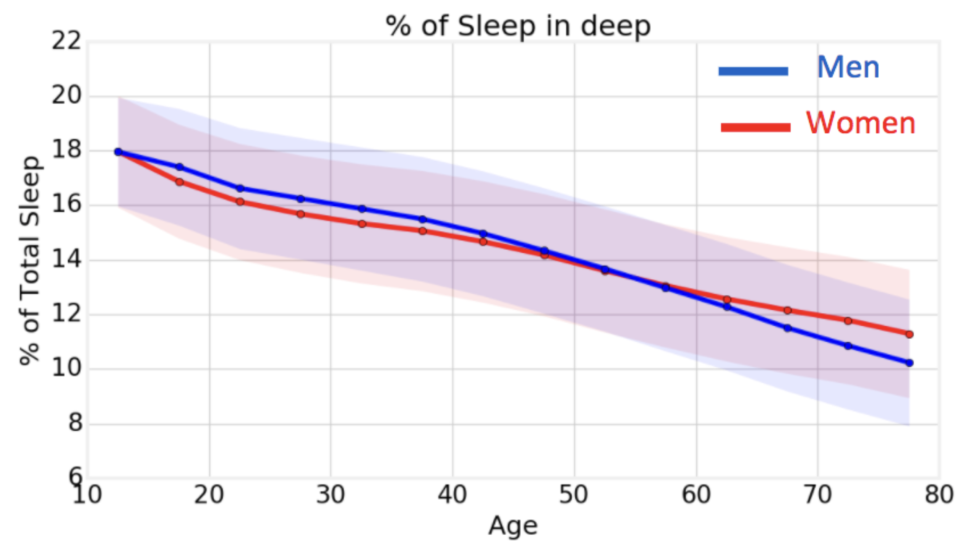

Getting older also affects your sleep. In this graph from Fitbit’s sleep study, you can see that we get less deep sleep as we age. When you’re 20, you’re getting half an hour more deep sleep a night than when you’re 70.

North vs. South

Yes, it’s true: Northerners go to bed five minutes earlier than Southerners. They wake up earlier, too.

That may seem like a very small difference, but on the scale of billions of data points, it’s significant.

On the other hand, Heneghan points out that statistics can be tricky. “I think North/South may be an artificial divide; urban/rural is probably a more meaningful divide,” he notes. In other words, there may just be more big cities in the North.

East vs. West

East Coasters, according to the data, stay up seven minutes later than West Coasters (and wake up five minutes later, too).

“I personally find this consistent with my experience of American culture,” Heneghan says. “I lived in New York. I lived in California. You get to 9 p.m. here in California, and the restaurant staff are kind of looking at you funny. There’s a great quote from Yogi Berra: ‘It gets late real early around here.’”

The national bedtime

Here’s a data point that no amount of sleep-lab studies could have unearthed: The average American goes to bed at 11:21 p.m.

Bedtime consistency

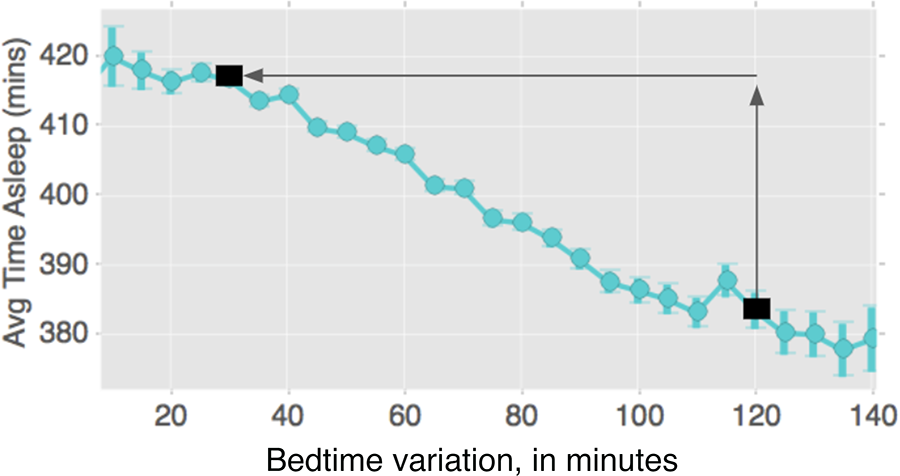

The biggest finding in Fitbit’s data may be the link between sleep quality and bedtime consistency.

That, Gleichauf explains, “is this idea that your bedtime varies.”

And in America, it really does vary — by an average of 64 minutes. You might go to bed at 11 p.m. on weeknights, but stay up after midnight on the weekends.

The Fitbit data shows that your sleep suffers as a result. If your bedtime varies by two hours over the week, you’ll average half hour of sleep a night less than someone whose bedtime varies by only 30 minutes.

And you’ll pay the price.

You know how jet lag works, right? “When you have jet lag, it’s the mismatch between the actual time, in the zone you’re in, and your circadian rhythm,” Gleichauf told me. “You’re not on the right part of that curve to make you fall asleep.” So, at night in your new city, you lie there for hours, unable to fall asleep — and then in the middle of the next day, you’re overcome by exhaustion.

When your bedtime varies over the week, then, you’re creating self-induced jet lag. Gleichauf calls it social jet lag: On Monday, when you have to go back to work (and drag your bedtime backward), you feel crummy and you’re more likely to get sick.

(Dr. Till Roenneberg, professor at the Institute of Medical Psychology at the University of Munich, calculates that every hour of social jetlag increases your risk of being overweight or obese by about 33%.)

“I’m super excited about this data,” Heneghan says. “For the first time ever, we were actually able to show the link between consistency and how long you sleep.”

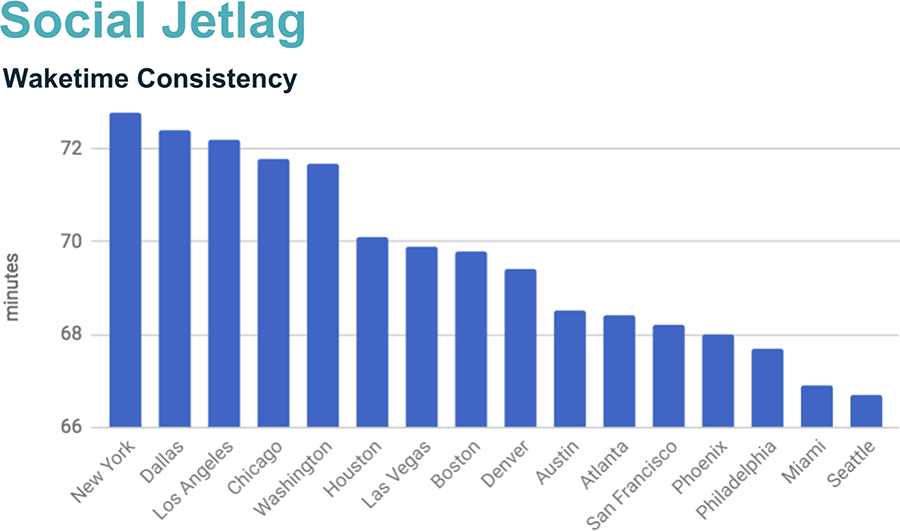

Social jet lag, by city

Gleichauf dove into American geography to see if there were differences in bedtime consistency — and there is.

Can you guess which city has the most widely varying bedtimes over the week?

It’s Boston — probably because it’s a huge college town, with a huge population of young people.

Can you guess which one has the least variation in bedtimes?

It’s Las Vegas. “People who live and work in Las Vegas — if they’re in the industry of nightclubs and casinos, their schedule is going to be much less weekend-dominated,” Heneghan says.

Wake-up times also vary. This time, Seattle is the winner, with the least variation across the week. The losers here are New Yorkers, whose wake-up times swing an average of 73 minutes over the week. (Well, it is the city that never sleeps.)

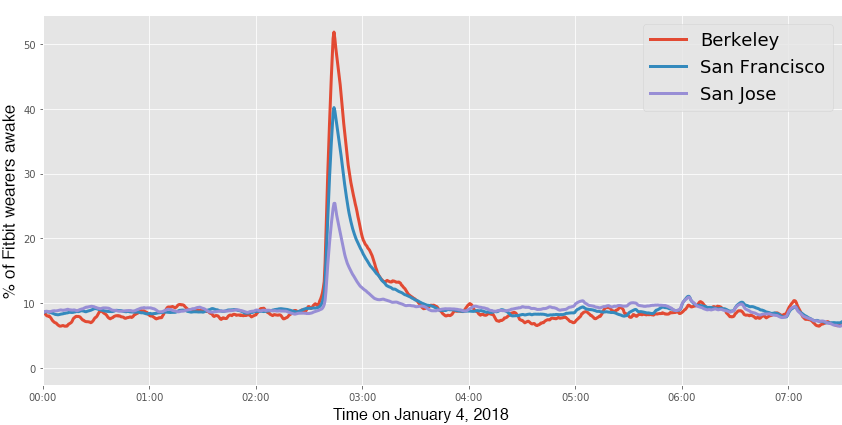

There are also findings to be gleaned based on time and location of a particular event. Look at what happened to people’s sleep in the San Francisco area this week when the earthquake struck:

The takeaways

The reporting that Fitbit’s sleep scientists offer in this exploration is only the very, very beginning. The company has amassed big data — big sleep data — that could provide some incredible answers. We just have to ask the right questions.

Why do men and women sleep differently? Why do we get less deep sleep as we age? Beyond the “party on the weekend” effect, why do our bedtimes vary so much? We know that exercise is good for our sleep, but when should we exercise for the best sleep? When should we eat if we want to get the most deepest sleep? Is the kind of sleep (REM sleep, deep sleep) more important than the total time asleep? Should the nation’s school hours and work hours be adjusted to fit the way we actually sleep?

And, of course, there’s the elephant in the data room: Fitbit’s data comes exclusively from people who can afford a fitness band. Would the results look different if it came from a bigger group?

Fortunately, Fitbit plans to share its data, both with other scientific institutions and in science journals; it’s thrilling to think of the new knowledge that may result from it.

Until then, consider trying to get to bed at a more consistent hour throughout the week. You’ll sleep better, you’ll sleep longer, and you’ll feel better once you’re up.

Or just move to Las Vegas.

David Pogue, tech columnist for Yahoo Finance, welcomes non-toxic comments in the Comments below. On the Web, he’s davidpogue.com. On Twitter, he’s @pogue. On email, he’s [email protected]. You can sign up to get his stuff by email.

Read more:

Tech that can help you keep your New Year’s resolutions

Pogue’s holiday picks: 8 cool, surprising tech gifts

Google’s Pixel Buds: Wireless earbuds for the extremely tolerant

Study finds you tend to break your old iPhone when a new one comes out