Facebook still bristles with fake news

If you search for “Breitbart” on Facebook, one of the listings likely to pop up is a group featuring the news organization’s red logo, with more than 20,000 members. When you click to join, you’re asked to answer three questions, including whether you consider the government your enemy. But the group has no affiliation with the Breitbart news organization, and if an administrator lets you in, you’ll see a news feed consisting of mainstream news, conservative commentary and outright fabrications. The sketchiest posts link to fringe websites few have ever heard of.

Facebook is under the most intense scrutiny in its 17-year history, amid revelations that it ran political ads paid for by Russian interests during last year’s presidential election. Congressional committees plan to release those ads in coming weeks. Meanwhile, special counsel Robert Mueller is investigating the social media giant as part of his inquiry into Russian meddling in American politics. Facebook executives will soon testify before Congress, which may impose new regulations on social-media platforms that have largely evaded government intervention up till now.

But Facebook faces another pernicious problem that has earned less attention of late: Fake news pockmarks the platform, especially in membership groups where people go to find like-minded users. Much of the bogus information has a political slant, as the Russian ads that ran on the platform last year apparently did. But much of the phony info may serve a more banal purpose than influencing elections — simply making money by coaxing gullible users into clicking on outrageous-sounding posts that lead them to third-party sites clogged with cheesy ads for things such as “Hot Girls Fishing” and “Better Than Adderall.”

Is this garden-variety snake oil or Russian subterfuge? Hard to say. “The line between politically motivated disinformation and inflammatory content meant to drive clicks to websites is a blurry one,” says Tim Chambers, who runs the digital arm of the consultancy Dewey Square Group and authored a recent paper on the malicious use of social media. “Fake sites are often based out of Eastern Europe and interrelate with state-sponsored actions.”

I spent several days exploring fake news on Facebook using my personal account, and it wasn’t hard to find. When I searched for “Breitbart,” for instance, I found four different Facebook accounts using the name. But only one bore the check mark indicating Facebook has verified it’s legitimate.

I asked to join one of the unverified Breitbart groups and was granted access by a Facebook user dubbed Joel Busick, who has 0 Facebook friends and lists no personal information, except the claim that he’s from Sister Lakes, Mich. His profile picture is a jar of red fruit. These are all hallmarks of a fake account, according to cybersecurity experts.

The unverified Breitbart stream includes links to news stories from legitimate media sites such as Fox News, National Review and the real Breitbart. But I also found plenty of exaggerated or distorted takes on real news, such as a post in the unverified Breitbart feed declaring the “NFL lost [a] second MAJOR sponsor to kneelers.” When I clicked on the link, the “major sponsor” turned out to be a car dealership in Flemington, N.J.

There were total lies mixed in with real and exaggerated news. Several related to the Oct. 1 massacre in Las Vegas, with links to stories claiming there were multiple shooters rather than one. Another post linked to a story insisting nobody fired from the Mandalay Bay Hotel where shooter Stephen Paddock did, in fact, fire from. A third post declared that Paddock had a direct link to Barack and Michelle Obama. All claims are demonstrably false. Another post claimed that rapper Eminem led an anti-Trump chant at a recent concert (true) and also wrote a check to Trump’s 2020 re-election campaign (false). Then there was a poll in the unverified Breitbart feed that asked, “Do you support the Second Amendment?” When I clicked on it, the link that popped up asked for my email address instead of allowing me to vote. I declined to provide it.

There’s a separate “Breitbart News” group — also unverified — that appears linked to the unverified Breitbart group. When I asked to join that group, an administrator using the name “Izzy Wilshire” let me in. Like “Joel Busick,” Izzy Wilshire has no Facebook friends, and there’s no personal info at all. The profile picture is a mashup of a woman’s face and a wolf’s, which appears to be downloaded from Pinterest, according to a reverse image search I conducted on Google. Izzy Wilshire posts inflammatory messages in both unverified Breitbart groups. A typical one: “Go To Hell!” in response to Eminem’s anti-Trump chant. Another Breitbart News admin who posts similar items is “Carlos Hondo,” who has more than 600 Facebook friends, including many that appear to be real people. But Carlos Hondo lists no personal information, and his profile picture is an image of Beric Dondarrion, the nomadic warrior from “Game of Thrones,” wielding his familiar flaming sword.

Breitbart did not respond to several requests for comment regarding this story. A Facebook spokesperson issued this statement to Yahoo Finance: “Groups that use brands in their names don’t violate a specific policy on Facebook, as many groups don’t self-identify as ‘official’ groups and are intended to be fan groups or spinoff discussion groups. However, people want to see accurate information on Facebook, and so do we. We’re aggressively pursuing a multi-pronged approach to stop the spread of false news, and while we have much more work to do, just this week we announced that when a story has been fact-checked as false, it loses 80 percent of its future impressions on Facebook.”

Monitoring posts is a challenge

Bogus news inside member-only groups highlights a unique feature of Facebook: The site is highly compartmentalized, with members of the public only able to see what’s in their own news feed (assuming they’re on Facebook in the first place). That’s a huge selling point to advertisers, since Facebook can target ads to individual users based on everything it knows about their likes, dislikes, interests, and even personality traits detected via the quizzes and games that pop up from time to time on the site. But you have to be admitted to a group to see what’s shown there, a setup that makes public oversight impossible. Users can see content posted in other people’s news feeds, but only if they’re “friends.” Even then, one user wouldn’t necessarily see an ad served to another user. Twitter, by contrast, is generally open to anybody with an account, since a user can follow anybody and see what they post.

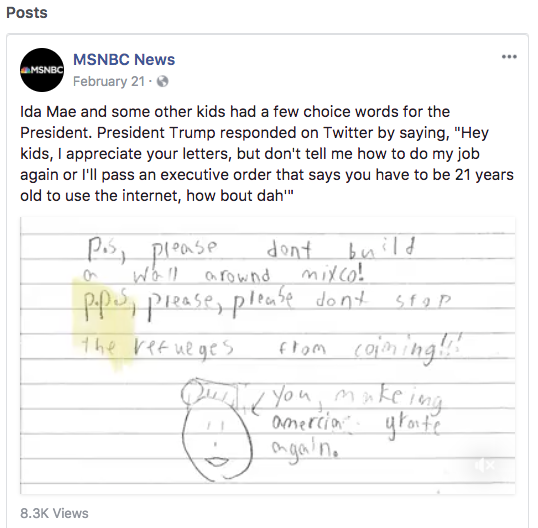

Since the unverified Breitbart groups I found were appropriating the name of a conservative news site, I searched to see if other groups did the same thing with different news organizations. I found an unverified CNN page, but it had few followers and no recent posts. An unverified MSNBC page — not requiring membership — had about 9,100 likes, and the newest post was from February. But that post claimed President Donald Trump had responded to kids writing letters to the White House by tweeting, “Don’t tell me how to do my job again or I’ll pass an executive order that says you have to be 21 years old to use the internet.” Trump never tweeted that.

Conservative causes seem to be more susceptible to fake news than liberal ones, and perhaps a more lucrative target for fake-news profiteers. But liberal causes aren’t immune. During last year’s campaign, there were 30 or more pro-Bernie Sanders accounts on Facebook that turned out to be operated by users based in Macedonia and Albania. Info from those accounts — much of it bashing Hillary Clinton, Sanders’s foe in the primary elections — “reached hundreds of thousands of Facebook users via hundreds of posts,” according to a recent report by NDN, a center-left think tank in Washington, DC. It’s not clear if those accounts had any connection with Russian interests, or were just an attempt to lure users to ad-heavy web sites.

Macedonia is home to a fake-news syndicate

In addition to bogus Facebook accounts borrowing brand names, I also spent some time looking into political groups on Facebook that don’t claim to be affiliated with a news organization or political candidate. There are several pro-Trump “deplorable” groups, for instance, and when I asked to join The American Deplorables, which has 41,000 members, a Facebook user named Димче Г?уров —Macedonian that transliterates to Dime Djurov — gave me permission to join. Djurov appears to be a real Facebook user, whose page says he lives in Veles, Macedonia. If the recurrence of Macedonia sounds surprising, it’s not. There’s basically a fake-news syndicate in Macedonia, as several news organizations have revealed, mostly operated by young men who get paid by third-party operators for leading Facebook users to external websites clogged with ads. Facebook supposedly cracked down on the racket earlier this year, but evidently didn’t nail everybody.

Since the Macedonian-style accounts make money when Facebook users click off to a third-party site and see an ad, there’s an incentive to make Facebook posts linking to those sites as provocative as possible. In the feed running inside The American Deplorables group, I found a mix of real, distorted and fake news, similar to what I found in the counterfeit Breitbart group. Examples of fakery: Michelle Obama said that if Trump deports Muslims, her family will leave America, too; a “sad announcement about Nancy Pelosi” linked to a nonexistent third-party page; and President Obama was behind a 2015 terrorist attack in Texas. That last item was posted by Филип Крстевски, who appears to be a Serbian otherwise known as Filip Krstevski.

Facebook’s credibility

My fake-news survey of Facebook is obviously anecdotal. But it’s virtually impossible to do a thorough analysis to determine how prevalent fake news is on Facebook. Twitter releases some user data publicly, which has allowed researchers to estimate that as many as 15% of Twitter’s 300 million accounts might be fake. Facebook guards its data much more closely, making outside analysis difficult. In its latest quarterly filing with the SEC, Facebook estimated that 1.5% of its 2.01 billion monthly users were “undesirable.” Facebook also said, however, that its estimate “may not accurately represent the actual number of such accounts” because it’s based on a “limited sample.”

Facebook has been losing credibility with the public, meanwhile, and with Washington as well. Last November, CEO Mark Zuckerberg said it was a “pretty crazy idea” that fake news on Facebook might have influenced the U.S. presidential election. That was before Facebook itself discovered that Russian interests had purchased political ads meant to sway the election in Trump’s favor. Facebook’s Chief Operating Officer, Sheryl Sandberg, acknowledged recently that “things happened on our platform in this election that should not have happened.”

Facebook says it is hiring 1,000 new staffers to help monitor ads and content for problems, but it has made similar promises before to crack down on problematic content. Members of Congress may decide that new legislation is necessary to police political content on Facebook and other social media sites, much as political ads are regulated in the traditional media. One suspects fake news will persist anyway.

Confidential tip line: [email protected]. Encrypted communication available.

Rick Newman is the author of four books, including Rebounders: How Winners Pivot from Setback to Success. Follow him on Twitter: @rickjnewman