Facebook’s push to kill bad political ads is also hiding regular posts

Facebook (FB) wants you to know that it’s not going to fall for that Russian-fake-news trick again. As it gears up for elections in the U.S. and elsewhere, the social networks has been deploying multiple defenses against the disinformation campaigns that overran the company throughout 2016. You’ll recall CEO Mark Zuckerberg initially brushed off those same issues as a small, inconsequential issue.

“In retrospect, we were too slow,” chief product officer Chris Cox admitted a conference Facebook hosted in Washington Tuesday. He and other company executives vowed that Facebook would do better, thanks to countermeasures already being deployed.

Many of these steps—in particular, a crackdown on fake accounts—look like good moves. But Facebook’s attempt to force transparency on politically-oriented advertising is already tripping up non-political advertisers, from apartment listings to news stories.

Not even Facebook seems happy about the results so far. But the company can’t blame anybody but itself for having let things get to this point.

Loaded language

Facebook had to do something because it had left its ad system open for abuse. An advertiser had to do little to prove its identity before using Facebook’s extensive demographic and interest data to target users with striking precision, leaving other users oblivious to such “dark ads.”

After declaring last summer that it wouldn’t get into details about how bad things had gotten, Facebook has been busy backpedaling.

In September, Zuckerberg said that the company would require any buyer of ads for or against specific candidates to disclose their identity, and then keep all those ads visible to anyone that visits their pages. A month later, Facebook said it would also require election ad buyers to confirm their identity offline.

And in April, the company said it would extend these verification and transparency rules to buyers of ads addressing political issues, not just candidates. It would also maintain an online archive of all political ads to inventory their targeting and performance.

How does Facebook know what makes an ad about a political issue? Its rules start with 20 key words and phrases:

abortion

budget

civil rights

crime

economy

education

energy

environment

foreign policy

government reform

guns

health

immigration

infrastructure

military

poverty

social security

taxes

terrorism

values

Running ads that Facebook deems political entails a verification process that starts with submitting a scan of your driver’s license or U.S. passport, as well as providing your mailing address and the last four digits of your Social Security number.

You then have to wait for Facebook to mail you a letter—yes, on paper—with a confirmation code that you enter at Facebook’s site to confirm your U.S. location. Without all that, Facebook will take down the theoretically-offending ad.

Other social networks may follow this path. Twitter (TWTR), for example, says it’s working on its own issue-ads policy.

A disappearing act for ads

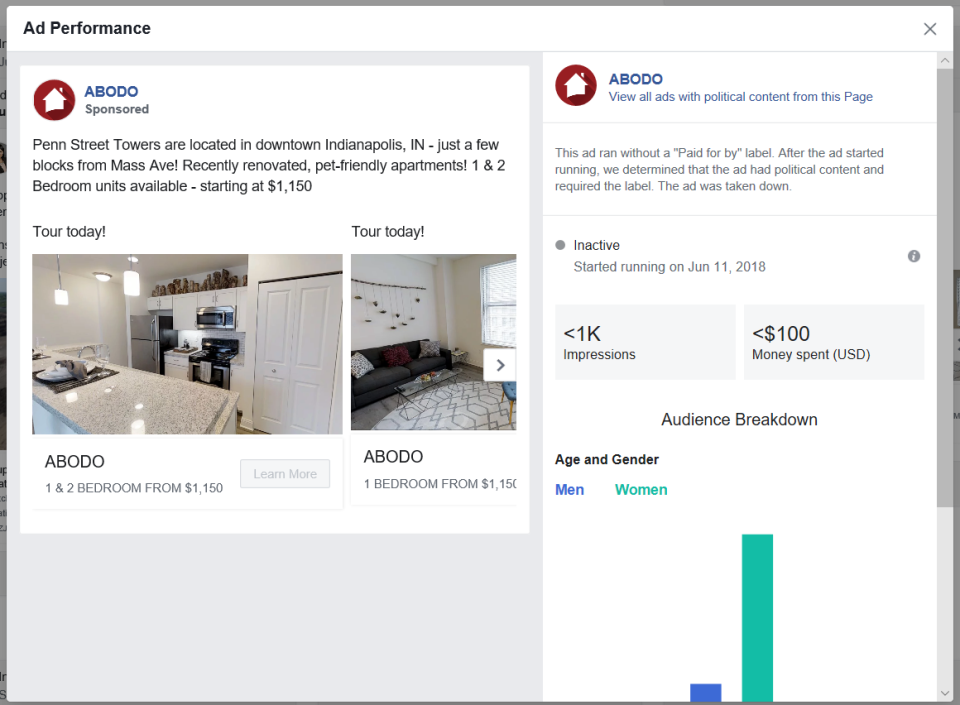

These rules went into effect May 24, and a look at their results as shown in Facebook’s political-ads archive—facebook.com/politicalcontentads—already shows problematic results.

A query for “apartments,” for example, yielded dozens of obviously political ads but also a Brooklyn apartment building’s shout-out to Pride Month, a New York TV station’s report about the city housing authority and listings for a complex in Indianapolis.

A search for “airline” showed that Facebook had taken down an ad for a business-news story about the Asian commercial-aviation market and a promoted post by a former flight attendant alleging sexual assault by a coworker.

“The way Facebook’s classifying issue ads is quite broad,” said Miranda Bogen, an analyst with the policy group Upturn. She cited checks by that Washington-based non-profit (in May, it published a study critiquing Facebook’s initial ad-transparency steps) that found “purely factual information” tagged as political.

“That’s obviously a problem for advocates who are trying to provide resources to different groups,” she said, citing immigration issues in particular. “The same with news organizations; if they’re even writing about a topic that is among the issues Facebook has listed as political, it’s listed as a political ad.”

Indeed, Pro Publica documented numerous false positives in a report last week. And what if I try to promote this story on Facebook by noting that the words “economy” or “environment” can get a story sent into political-ad exile? I think we know the answer.

It appears that ads can escape this purgatory—in second searches of the ad archive for the same term, some false-positive results no longer appeared—but Facebook doesn’t seem to document an appeals process.

The company has, however, pledged to treat ads for news stories differently… somehow. Wednesday, ads manager Rob Leathern tweeted that it had to flag them “to prevent workarounds for bad actors” but would soon “launch a separate section in our archive for news ads about politics.”

It’s not like Washington is helping

The idea that an automated screening process could go disturbingly wrong shouldn’t be a stretch. See, for example, when YouTube decided a video of a giant American flag at a football game wasn’t eligible for advertising income.

But while it’s tempting to blame Facebook for once again placing too much faith in its algorithms, you can’t accuse the company of doing so out of self-interest. By making its own ads an unreliable medium, it’s hurting its own bottom line and encouraging businesses to find more stable platforms.

And meanwhile, it’s not like anybody else is doing much. Last year’s Honest Ads Act, which would require most online ads addressing specific candidates to meet the same disclosure standards as on radio and TV, has yet to advance past committee in either the House or the Senate.

Facebook may be making a mess of this. But Congress isn’t trying to make a change at all.

More from Rob:

How Europe’s proposed copyright laws could ruin your search engines

Why the death of net-neutrality rules will be a big campaign issue

Email Rob at [email protected]; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.