A primer on the Fed's corporate bond-buying program

The Federal Reserve on Monday fired up its facility to directly purchase corporate bonds from the companies themselves, rounding out its bond-buying program as the central bank continues to combat the economic fallout from the COVID-19 crisis.

Since May, the Fed has already had a hand in the corporate debt market, snatching up billions in corporate bond ETFs and, as of late, purchasing individual bonds in the secondary market as well. On Sunday, the Fed announced the “broad market index” that will guide its individual purchases, including familiar names like Apple, General Electric, and Comcast.

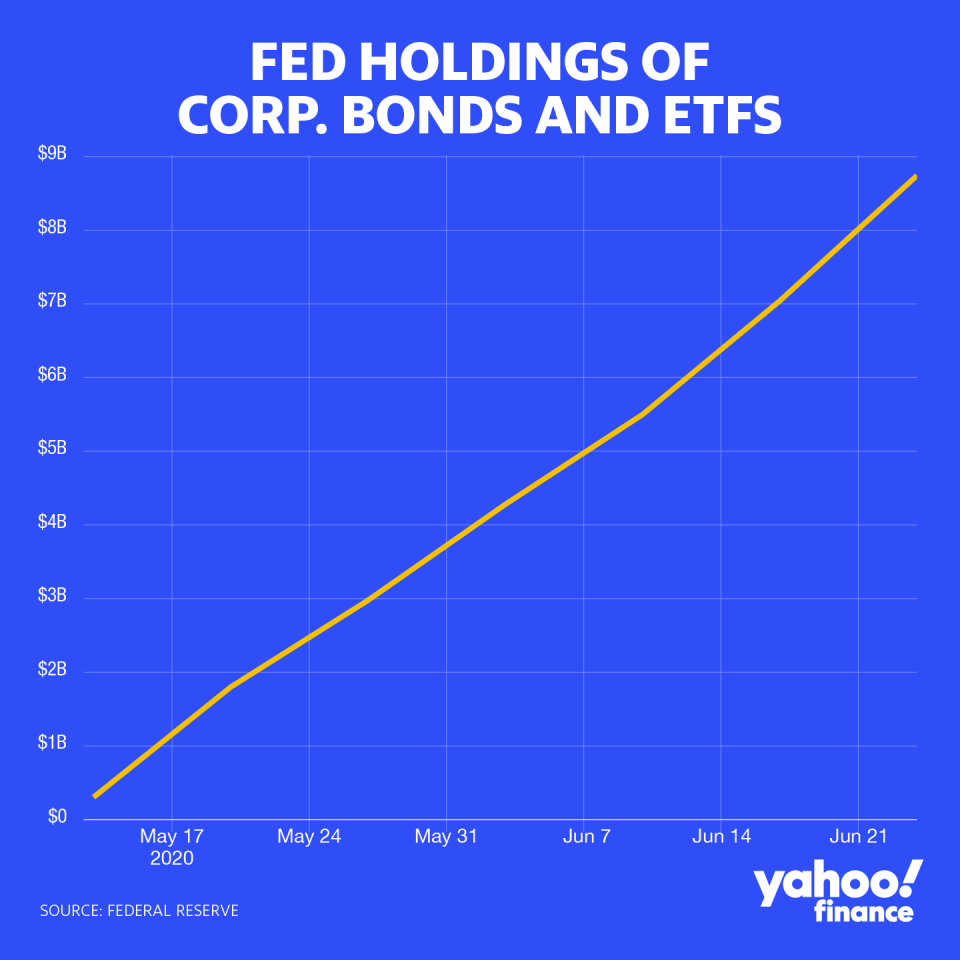

As of June 24, the Fed’s purchases had only totaled $8.7 billion, a drop in the bucket when considering the Fed could lever its purchasing power to take on as much as $750 billion in assets. Upon launching its facility to directly buy debt from issuers, Fed officials said they expect limited usage of the facility, adding that corporate credit markets appear to be past the illiquidity from mid-March that manifested itself in the form of blown-out spreads.

Still, the Fed’s corporate bond intervention raises questions about how the Fed will go about the purchases and why it needs to backstop the corporate credit market at all.

What is the Fed buying exactly?

The Fed is bucketing its purchases into two categories: corporate bond ETFs and individual corporate bonds themselves.

Corporate bond ETFs are baskets of corporate debt bundled together by issuers like Blackrock or Vanguard, and sold to investors. There are several types of corporate bond ETFs that target different maturities (i.e. short-term or long-term) or credit quality (i.e. investment grade or junk-rated). As of June 16, the Fed had purchased about $6.8 billion across 16 different ETFs, the bulk of which in Blackrock’s LQD and Vanguard’s VCSH, and VCIT.

Beginning June 16, the Fed also began purchasing individual corporate bonds in the secondary market. Its first round of disclosed purchases included about $429 million in bonds including holdings of debt from Abbvie, AT&T, and UnitedHealth Group.

Its operations so far have been part of its Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF) since the ETF and individual bond transactions are done in the secondary market. But the Fed on Monday announced that it had fully stood up its Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF), which will purchase qualifying bonds and portions of syndicated loans or bonds at issuance.

Why is the Fed buying individual corporate bonds?

When the economy was spiraling out of control in the second half of March, the Fed announced it would backstop corporate credit markets. At the time, the concern was that a dramatic tightening of financial conditions would leave companies with nowhere to turn if they needed to issue debt to survive the crisis.

The Fed announced both the PMCCF and the SMCCF, committing up to $750 billion of purchases when it unveiled term sheets for the programs in early April. But the Fed did not stand up either facility until May 12, at which point conditions in the corporate financing markets appeared to ease.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has faced questions from Capitol Hill on why the Fed still feels the need to step into the corporate debt market if funding pressures have been relieved.

“I don’t see us as wanting to run through the bond market like an elephant doing things and snuffing out price signals or anything. We want to be there if things turn bad in the economy,” Powell insisted in Congressional testimony in mid-June.

How is the Fed picking which companies to buy bonds from?

The Fed has enlisted Blackrock as its investment manager and State Street as its custodian for its corporate bond programs.

For the SMCCF, Fed has said from the beginning that it has wanted its purchases to get “broad exposure” to the corporate debt market, wary of the optics of favoring certain industries or companies over others. But the criticism of the Fed purchasing a large share of its ETFs in Blackrock-issued funds may have driven the central bank toward a different approach: building its own portfolio.

In mid-June, the Fed announced that its purchases would be guided by a “broad, diversified market index.” On Sunday, the New York Fed published the index for the first time, which detailed the 794 companies it plans to buy corporate debt in, alongside weights for how substantial those investments will be. The Fed insists that it will update the index every four to five weeks.

Unlike the SMCCF, the PMCCF will not involve the Fed going into the market to buy corporate bonds. Instead, companies will have to get certification from the New York Fed before selling bonds to the Fed facility.

So is the Fed rescuing junk companies?

The Fed has said it will primarily focus its purchases on investment-grade corporate debt, with the “remainder” going to some high-yield (or less gratuitously, “junk”) bonds. Through both the PMCCF and the SMCCF, the Fed will only take on junk debt if the issuer had investment-grade ratings before March 22 and subsequently faced a downgrade. So-called “fallen angel” companies include the likes of Ford and Delta. The idea behind the March 22 cut-off: to identify companies that were facing financing problems as a result of the COVID-19 crisis.

As of June 5, the Fed was targeting only 2.8% of its index in junk rated (BB) bonds. The Fed hopes to have about 54.8% of its index in investment-grade bonds (BBB) and the remaining 42.4% in high credit quality (AAA/AA/A) bonds.

Why are there foreign companies in the Fed’s index?

The Fed has said it is targeting U.S.-listed ETFs with exposure to U.S. corporate bonds, but the Fed’s broad index includes foreign names like Toyota, Volkswagen, and Daimler. But the Fed’s disclosure makes it clear that the central bank is targeting purchases of debt issued by their U.S.-incorporated subsidiaries.

For example, the Fed is not targeting Volkswagen debt issued by its German parent company, but debt issued by its U.S.-based Volkswagen Group America.

Regardless, the heavy weights on U.S. subsidiaries of foreign car manufacturers may reflect the importance of their manufacturing plants and auto loan portfolios stateside.

How long is the Fed going to do this?

Both facilities will purchase assets through September 30, 2020, but the Fed could extend that timeline if needed.

What will the Fed do with the bonds it bought?

It is not so clear how the Fed will exit its holdings.

Bonds purchased through the SMCCF can have a remaining maturity of up to 5 years and bonds purchased through the PMCCF can have a maturity of up to 4 years. The Fed says it can support the facilities through maturity (at which point the asset would roll off), but said it could also sell the bonds in the open market.

The Fed’s plan for its ETF holdings are also unclear.

Brian Cheung is a reporter covering the Fed, economics, and banking for Yahoo Finance. You can follow him on Twitter @bcheungz.

Fed to cap bank dividend payments after completing stress test, COVID analysis

IMF projects 4.9% economic contraction as concerns mount over second wave

Boston Fed's Rosengren: Second half of 2020 will be 'more difficult' than anticipated

A glossary of the Federal Reserve's full arsenal of 'bazookas'

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.