Defining a 'hot' labor market: Yahoo U

The Federal Reserve was once optimistic that it had reached maximum employment, one of its dual mandates as assigned to it by Congress.

But defining maximum employment is an inexact science, and policymakers are acknowledging that despite 50-year lows on unemployment, the labor market may still have room to grow.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell said Wednesday that he would like to see higher wages before hiking rates again, reinforcing the Fed’s messaging that it could be on pause on rate moves for a while.

One reason: the Fed feels comfortable allowing accommodative interest rates to further strengthen the labor market. And Powell may not see a case for raising rates until wages bid higher.

“The labor market is strong, I don’t know that it’s tight because you’re not seeing wage increases,” Powell said in response to a question from Yahoo Finance on Dec. 11. “Ultimately if it’s tight, that should be reflected in higher wage increases.”

The semantics of describing the labor market as “strong” but not “tight” acknowledges that the Fed has not reached “maximum employment,” one of its dual mandates. Over the past few years, the Fed has continually blown through its own estimates of how low the unemployment rate could go.

Estimating Maximum Employment

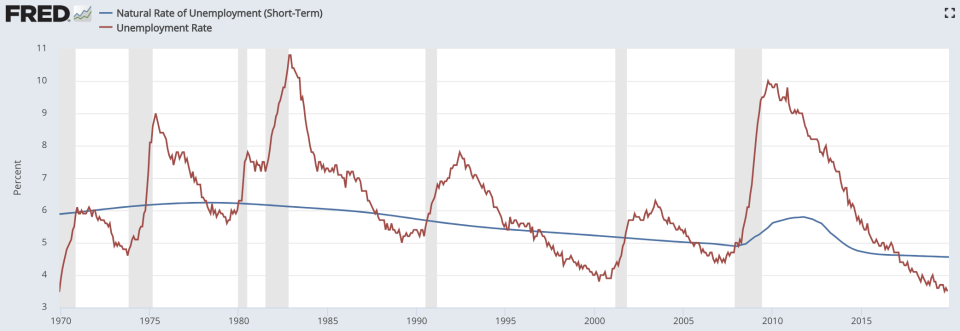

The Congressional Budget Office has an estimate for maximum employment referred to as the “natural rate of unemployment,” or u* in short-hand. This is the rate of unemployment where available resources in the labor market are supporting the normal, unstimulated growth rate of the economy.

In theory, if unemployment is higher than where the economy’s “natural” employment level is, then too many workers are being left on the sidelines and the economy is underperforming its potential output (a negative output gap).

But when unemployment is lower than the natural rate, then there may be too many jobs looking for workers in the market, thus bidding up wages as employers compete for talent. In this case the economy is overperforming its potential output (a positive output gap).

Higher wages are obviously a positive thing for workers, especially for marginalized, low-income workers. But on a macroeconomic level central banks will not want wages to rise so fast that it spurs runaway inflation. Because economists associate a “hot” labor market with rising inflation, the natural rate of unemployment is also called the “non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment.”

Steering the unemployment level is therefore a delicate balance. But complicating things further; the Fed doesn’t actually know where u* is.

Fed Vice Chairman Richard Clarida has said in the past that u* is “unobservable and must be inferred from data via models.”

Moving targets

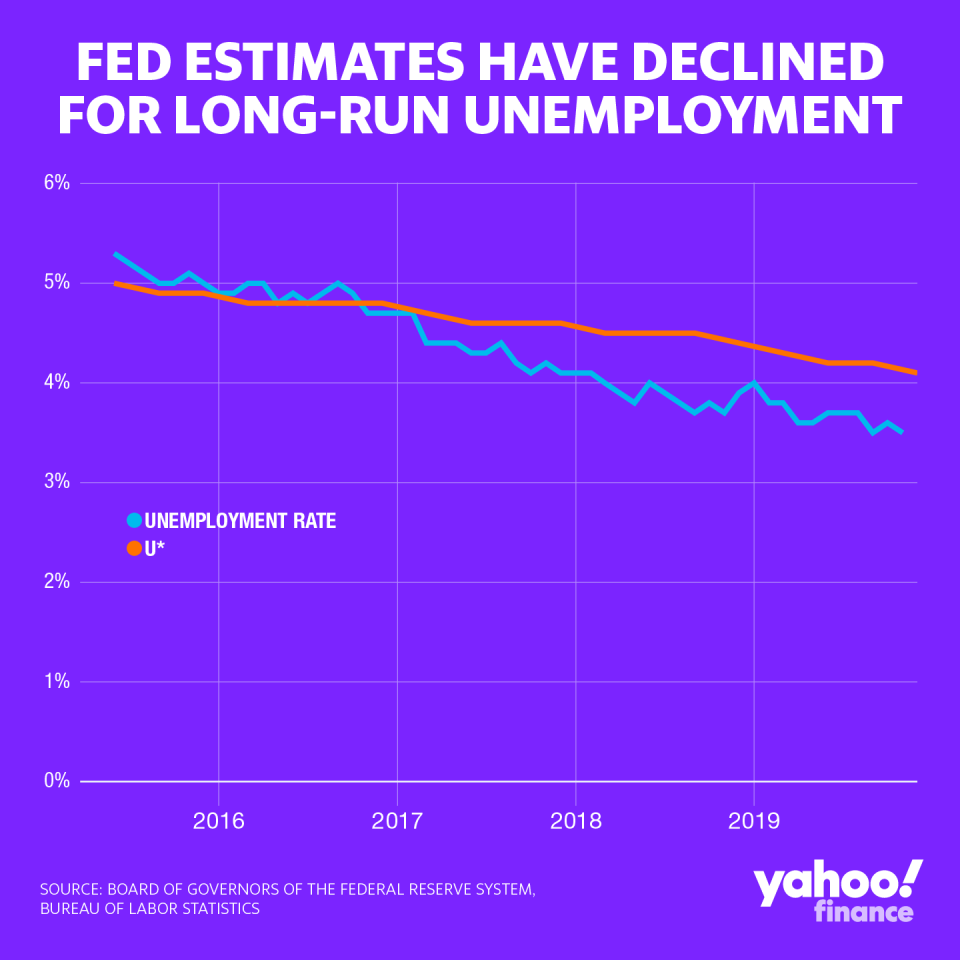

The Federal Open Market Committee releases quarterly economic projections of its own for u* and other economic variables like output and interest rates.

In 2015 and 2016, the Fed began hiking rates as it saw unemployment rates hover near its own estimates for u*. In mid-2016, when unemployment was at 5.0%, then-Fed Governor Powell said the labor market appeared “close to the level that many observers associate with full employment.”

To get ahead of possible inflationary pressures, the Fed continued to hike rates. But unemployment continued to fall lower. Over that time, the Fed gradually moved the goal post for where it sees maximum employment, from near 5% to 4.1% as of the December 2019 meeting.

“We raised rates beginning in December 2015 to get ahead of inflation,” Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari told Yahoo Finance on Oct. 10. “We raised rates early, the inflation never came.”

Wage growth rose higher until the Fed began tightening policy, and with the Fed now on pause after cutting interest rates three times in 2019, policymakers appear to be content with keeping rates low until wages bid meaningfully higher.

Powell has said this would best support low-income workers who have been sidelined for much of the recovery. Until wages rise higher, Powell says the labor market is “strong” but not “tight.”

“These developments underscore for us the importance of sustaining the expansion so that the strong job market reaches more of those left behind,” Powell said Dec. 11. “We expect the job market to remain strong.”

Brian Cheung is a reporter covering the banking industry and the intersection of finance and policy for Yahoo Finance. You can follow him on Twitter @bcheungz.

Fed holds steady on rates, may continue to hold through 2020

Fed in focus as worries mount over a year-end repo market flare-up

‘The weirdest place in the world’: What the Fed missed in Jackson Hole

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.