Fed squeezes liquidity into system as it tries to regain control of rates

The Federal Reserve rushed to inject liquidity into the financial system on Tuesday and Wednesday as it tries to wrestle control over interest rates.

Over the past two days, borrowing costs surged as market participants scrambled for funding, pushing the effective federal funds rate to 2.30% as of Tuesday night, above the Fed’s target range of 2.00% to 2.25%. In focus: the repurchase agreement (or repo) market, where banks and Wall Street dealers lend to one another overnight to meet day-to-day financing needs.

A lack of available bank reserves to support the interbank lending have led to higher interest rates. The New York Fed stepped in on Tuesday morning, overcoming technical difficulties to offer the first repo program of substantial size since 2008.

“Sustained [federal funds] pressure will likely raise questions about the Fed’s ability to control money markets, especially as federal funds approach the upper end of the Fed’s target range,” Bank of America Merrill Lynch wrote Tuesday morning, when the effective interest rate was right at 2.25%.

But others said concerns over Fed credibility may be overblown, as the spike in interest rates appears to be the result of a temporary flurry of financing needs associated with the timing of corporate tax payments and Treasury auctions.

To address the short-term crunch, the New York Fed’s trading desk announced that it would supply some liquidity by buying up to $75 billion in repurchase agreements, in which the bank buys up Treasury and federal agency debt and sells them back when the repo expires.

The desk originally planned to carry out the operation at 9:30 a.m. ET on Tuesday, but “technical difficulties” delayed the repo program by about 25 minutes.

The auction ended up generating about $53 billion in agreements. On Wednesday morning the New York Fed re-opened its large repo facility (on time) and auctioned the maximum amount of agreements at $75 billion. With funding pressures expected through at least the rest of the month, the Fed could continue to rely on its short-term funding facility to relieve pressures on interest rates.

The wonky episode adds another wrinkle to the Fed’s looming decision on interest rates, as policymakers prepare the next moves on interest rates this afternoon.

Nomura’s Lewis Alexander wrote Wednesday that the repo crunch will nudge the Fed to move “sooner rather than later” and possibly restart growth in the Fed’s balance sheet to support more bank reserves in the system.

Why the spike?

The repo market provides critical short-term cash for dealers to finance Treasuries and other securities, making these overnight loans the “plumbing” of the U.S. financial system.

In the case of spiking repo market rates, borrowers appear to be pressured by corporate tax payments and settlement of newly auctioned U.S. Treasuries. With bank reserves hard to come by, some dealers were paying as much as 10% for repo agreements on Tuesday.

The Secured Overnight Financing Rate, the Fed’s measure of the cost of overnight borrowing collateralized by Treasuries, skyrocketed from 2.20% on Friday to 5.25% this week.

The liquidity crunch was anticipated by some shops on Wall Street. Bank of America Merrill Lynch had warned that the due date on corporate tax payments would pull $75 billion to $100 billion out of funding markets. All the while, the U.S. government is hoping to fill its Treasury general account (TGA) by funding $155 billion of debt over the course of September.

“The TGA rebuild today represents a large reserve drain and the withdrawal of this cash from money markets has materially tightened funding,” BAML wrote Sept. 17.

But both of these forces appear to be temporary, writes Peter Tchir at Academy Securities. Tchir said that 1-month repo rates and 3-month LIBOR appeared to show no spike, demonstrating that not all corners of overnight financing are flashing alarm signs.

“I think this will all be over in a couple of days and many of us will regret not having gone for a walk outside to get a cup of coffee on this beautiful day,” Tchir wrote Sept. 17.

What can the Fed do?

Although the Fed’s target range is aspirational, it uses a key tool to guide market interest rates to its target range: interest on bank reserves.

As the bankers’ bank, the Fed pays interest on reserves that banks leave at the Fed overnight. So if the Fed would like interest rates in the target range of 2% to 2.25%, it will pay something in the middle of that range to set a benchmark at which banks will hopefully lend to one another.

In May, the Fed did not move on rates but worried that market rates were pushing up against the higher end of its target range at the time, which was 2.5%. To guide rates lower, the Fed tweaked the interest that it pays on reserves from 2.4% to 2.35%.

When the Fed cut interest rates by 25 basis points in July, the central bank then lowered the interest that it pays on reserves by 25 basis points as well, to 2.1%.

Ahead of the Fed’s interest rate decision on Wednesday, a new question: If the Fed cuts by 25 basis points as widely expected, should it accompany the move with a more dramatic decrease in the interest on reserves?

Bank of America Merrill Lynch wrote that there is another option: use its balance sheet. BAML wrote that if the funding issues are bad enough, it could need another $250 billion in assets on its balance sheet to support the bank reserves needed in the overnight financing space.

The banks themselves have another suggestion: reduce regulatory requirements. Under the liquidity coverage ratio, banks are required to hold set levels of high-quality liquid assets as part of the post-crisis regulation’s efforts to insure the banking industry against significant stress.

The Bank Policy Institute, which represents some of the largest U.S. banks, warned at the beginning of the month that the regulatory requirements are already elevating demand for excess reserves, which would be be crunched further by the tax deadline and Treasury auctions this month.

“As a result, money market rates will become volatile as banks scramble for reserves,” the BPI predicted.

The BPI acknowledged that it is unlikely that the Fed will dramatically change the liquidity coverage ratio regulation, a key part of its efforts to beef up U.S. bank defense against the next crisis. But in late 2018, the Fed loosened liquidity requirements on some large regional banks as part of its efforts to “tailor” post-crisis regulations.

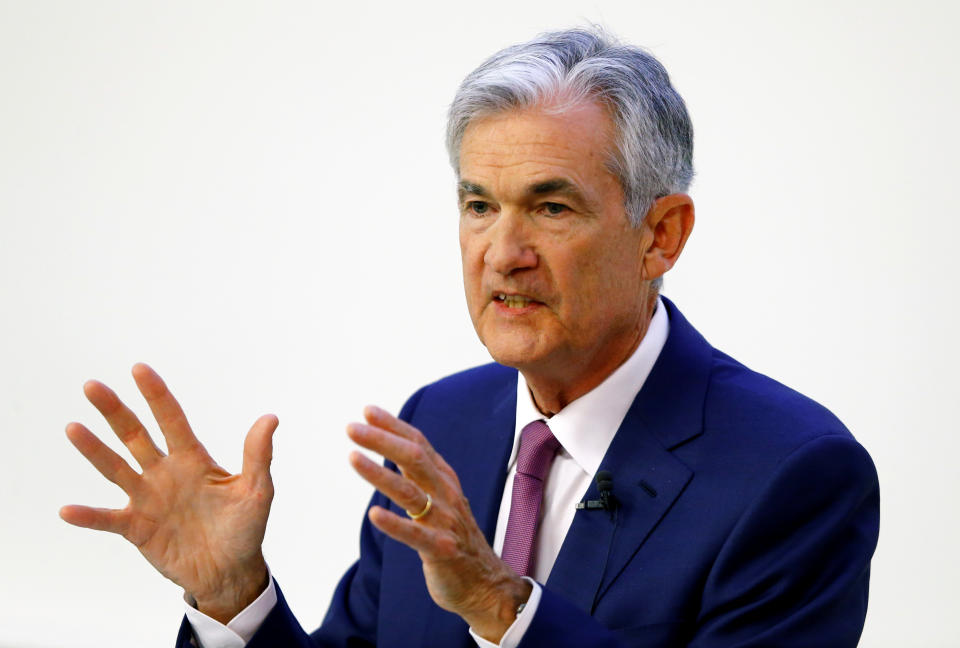

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell will be watched closely for commentary on these issues when he steps up to the podium for a pre-scheduled press conference Wednesday afternoon at 2:30 p.m. ET.

Brian Cheung is a reporter covering the banking industry and the intersection of finance and policy for Yahoo Finance. You can follow him on Twitter @bcheungz.

Trade tensions, oil shock cloud Fed efforts to steer clear of recession

‘The weirdest place in the world’: What the Fed missed in Jackson Hole

The Fed is thinking globally despite Trump's push for an 'America First' monetary policy

Congress may have accidentally freed nearly all banks from the Volcker Rule

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance