The first economic check-up of the Trump era won't be good, and that's just fine

On Friday, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) will release its first estimate of economic growth for the first quarter of 2017.

And the data for the $18.6 trillion U.S. economy looks set to disappoint.

Wall Street economists are anticipating the pace of growth to come in at just 1%, according to data from Bloomberg. Researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta estimate the economy grew at a measly rate of just 0.2% to start 2017, while researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s estimate growth to start the year hit 2.7%.

But gross domestic product (GDP) as measured by the BEA has some measurement issues that cast doubt on strong conclusions drawn from this headline number. And what’s more, the U.S. economy is about far more than one number.

President Trump has pledged 4% growth

Coming on President Donald Trump’s 99th day in office, this report will be the first major check on economic progress during the administration of a man who touted his skills as a businessperson, which he suggested would translate into economic growth for the nation. And just in time: in 2016, the U.S. economy grew just 1.6%, the slowest pace in five years.

The Trump administration has been pledging to return the economy to a 4% growth rate, which has not been seen since the 1990s. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has appeared to somewhat lower expectations, saying Trump’s policies could produce growth of 3%-3.5%. Similarly, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross said this week that “in time” he hopes the U.S. economy can achieve 3% growth.

And while this would exceed the pace of GDP growth seen during the Obama administration by a wide margin, initial data appears set to disappoint those who believed Trump would usher in a new era of economic growth.

What the soft and hard data tell us about the economy

The stock market has surged in the early days of the Trump era, and various White House officials — including the president himself — have embraced this as a reflection of success from the new administration. In this sense, then, the investor class appears to be telling a different story about the economy — since Trump’s election, the benchmark S&P 500 (^GSPC) is up 11%.

Economic data, however, has also not been uniformly negative since Trump’s election. In fact, economic news has, on balance, been quite strong. Measures like consumer and business confidence have surged to highs not seen in over a decade, while hiring remains solid.

Some have argued that “soft data” — or economic data based on surveys instead of collected sales or investments — have lagged “hard data,” indicating that this economic pop is a mirage. Neil Dutta, an economist at Renaissance Macro and a leading voice on discrediting this meme, noted Thursday that in the first quarter, capital goods shipments — a proxy for business fixed investment — rose at a seasonally-adjusted annualized rate of 7.5%, the best since 2014.

And if capital goods shipments are rising at the strongest pace in years, then the idea that “hard data” aren’t improving simply does not hold water. “The people who make this argument have ZERO credibility,” Dutta wrote.

Additionally, since Trump’s win, the Federal Reserve has twice raised interest rates, a sign from the world’s most important central bank that the economy is growing steadily enough to warrant less accomodative monetary policy. And while recent economic surprises have gone from overwhelmingly positive to a more neutral stance, economic news has been pretty good for the Trump administration.

GDP has measurement issues

When one looks for a comprehensive metric that reflects the success or shortcomings of the world’s largest economy, GDP is the number most often cited. But whether this one number is the best reflection of the state of the economy is up for debate.

“We don’t capture technology efficiently in GDP,” said Rick Rieder, Global Chief Investment Officer of Fixed Income at BlackRock.

Rieder argues that when you take into account the amount of hiring we’ve seen in the economy since 2010 and the rate at which personal consumption is growing, the amount of economic activity happening in the U.S. is clearly being understated by GDP figures.

“Vehicle miles traveled are at all-time record,” he said. “Gasoline consumption, all-time record. Air miles traveled, all-time record. Auto sales running at 17.5 million cars [per year]. Meaning, the number we get through GDP, it’s just not calculated right. And it just lags what’s changed in the way that the economy works today.”

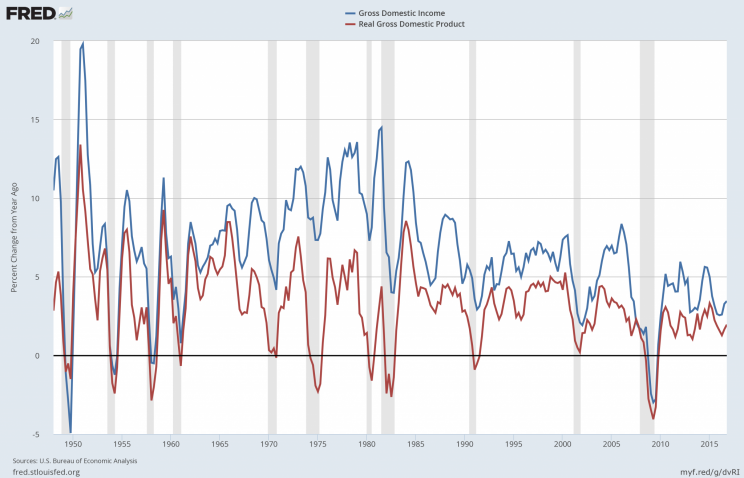

In addition to GDP, the BEA has started releasing GDI, or gross domestic income, as another way to measure economic activity in the U.S. And while in theory GDP and GDI should equal each other as the former measures what the economy puts out and the other what the economy takes in.

But because they use different data sources, these readings are subject to measurement error, though the BEA notes they tend to follow similar paths over time. A main difference in their inputs is tax receipts, with GDI taking into account taxes on production and imports, as well as subsidies, net interest, and miscellaneous payments.

Productivity may not be as low as the numbers suggest

Amid the disappointing overall GDP growth figures has been a decline in worker productivity, which is simply the amount of economic output created by each worker in the economy. For years, productivity growth been flat or declining, and many economists have viewed this as a core part of the thesis that we are mired in “secular stagnation,” or a new, lower trajectory for economic growth.

Others have seen productivity declines as the result of the economy simply running out of big, game-changing idea, with economist Robert Gordon perhaps best capturing this idea in his book “The Rise and Fall of American Growth.”

Gordon argues that one-time inventions like electricity, running water, and efficient air travel led to economic growth era that we will simply not experience again. And while this argument is appealing in that we can see the American economy’s primacy in the 20th century as a historical one-off, it also seems unlikely that a workforce universally connected to the internet, supplied with smartphones, and processing data at speeds that were impossible just a generation ago is getting, in effect, nothing done.

When trying to square slow productivity and disappointing GDP growth with the strength of the U.S. labor market, it seems that something isn’t quite right.

“We’ve hired 16 million people since 2010, that’s four times the population of Los Angeles and bigger than 46 states in the country,” Rieder said. “It’s a pretty remarkable number.”

And if we accept that productivity growth is flat, then workers are being hired to sit around and do nothing. But the nature of our current economy — one that is more weighted towards services than goods — provides challenges when measuring it via traditional methods that examine output per hour.

The healthcare worker at a nursing home, for example, provides a challenge in terms of measuring how much they are getting done at work relative to the manufacturing worker who produces a certain number of widgets each day.

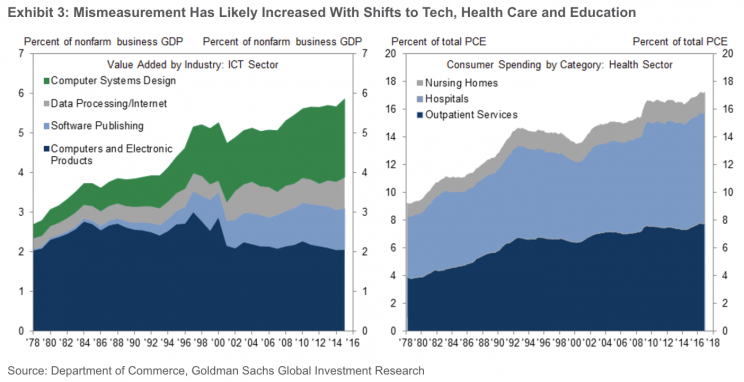

“US labor productivity has continued to grow very slowly, averaging just 0.6% over the past five years,” write economists at Goldman Sachs.

“However, we have argued for cautious optimism on productivity growth for two reasons. First, we forecast that measured productivity growth would increase gradually for cyclical reasons. Second, we think productivity mis-measurement has grown over time, implying that true productivity growth is now further above measured productivity growth than in the past.”

Goldman notes that government statistics likely overstate inflation and therefore understate productivity. Inflation numbers, the firm notes, are really just efforts at capturing raw changes in living standards. But the entry of new products like, for example, smartphones, has “always been difficult,” the firm write.

And as the firm writes, “The shift to sectors where quality growth is disproportionately hard to measure and the proliferation of free digital products have likely increased mis-measurement.”

The U.S. GDP report will be released at 8:30 a.m. ET on Friday.

—

Myles Udland is a writer at Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter @MylesUdland

Read more from Myles here: