How a gang of crooks hijacked your web browser

If you’ve had a “forced-redirect” ad hijack your web browsing today and wanted to curse out some of the cretins responsible by name, you can now do so. And the name is as tacky as you might expect: Zirconium.

The identification comes in a report by the ad-security firm Confiant that unpacks how this group of con artists staged a massive ad-fraud campaign last year that included creating 28 phony ad agencies.

It’s yet another haul of evidence pointing out deep-seated rot in the “programmatic” part of the online ad business, in which ad networks match open space on sites with potential advertisers through automated auctions.

A multi-level malware machine

The operation Confiant describes was larger than most: The New York company estimates that Zirconium’s “malvertising” got seen about a billion times last year, and in seven days of December showed up on 62% of a panel of 600 sites that it monitored.

But the con was also more complex, in that Zirconium built fake firms to sell fake ads. This operation, itself hidden behind a Scottish shell company, created an ad network named MyAdsBro (yes, somebody thought this was a good name for a firm meant to sound legitimate) and then spawned 28 bogus ad agencies.

These companies’ websites look extremely similar, complete with buzzword-laden sales pitches and links to Twitter accounts spouting such marketing mumbo-jumbo as “Try to get the eventual user in online marketing” or “The main thing in online marketing is to have a progress report.”

Most point to a LinkedIn profile with a strikingly polished portrait picture that a Google (GOOG, GOOGL) reverse-image search reveals to be a stock photo.

A few of these online storefronts look sloppier than others. For instance, one fake firm that claims to run 4,600-plus ad campaigns lists a British street address that Google Maps shows as a rundown block of townhomes.

“We believe Zirconium was progressively rolling out their agencies to overcome occasional bans, as they progressively got caught,” Confiant’s report notes. “The dormant ones progressively built precious reputation (mostly history, and social media following) to pose as established companies and maximize their potential of striking deals with more ad platforms.”

Evading capture

Confiant co-founder and chief technology officer Jerome Dangu said that his New York firm first saw signs of the ad-fraud operation last February.

“We only realized that this was an organized group as we started connecting the dots by October 2017,” he said. “When they continued to ramp up their operations through Q4 2017, we organized to collect as much data as possible and aggressively report them to platforms.”

Many ad networks did not want to hear the company’s warnings: “Multiple platforms were dubious of our claims, citing their own security processes, which delayed the reaction by multiple weeks.”

The report originally named two such firms, AdSupply and Voluum. Executives at both denied acting in that manner, and AdSupply CEO Justin Bunnell added that he was not aware of any inquiries from Confiant. Confiant has since edited its own post to remove any mention of either firm.

Oversight is a known issue in the ad industry, said Ryan Singel, co-founder of the publishing-tools firm Contextly: “If legitimate ad platforms actually did any due diligence, this scam would be far less profitable.”

Confiant also found that from October on, Zirconium’s malvertising began adding code to detect whether an ad was being served to a real person’s desktop computer or a browser running in a virtual machine set up by researchers to detect scam ads.

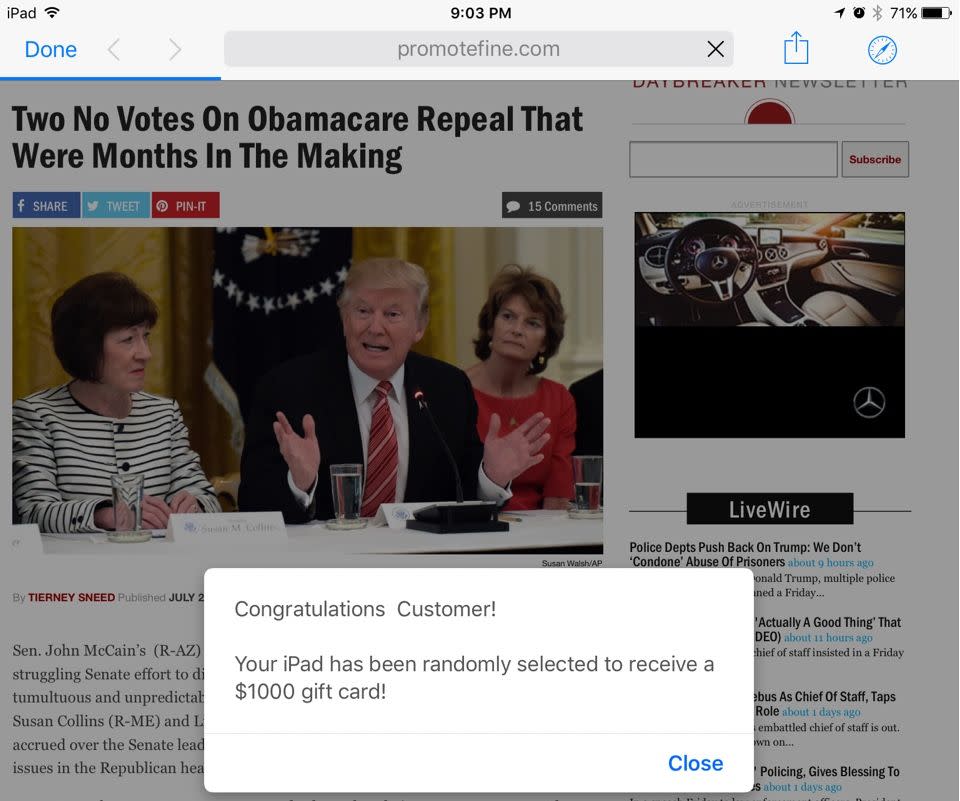

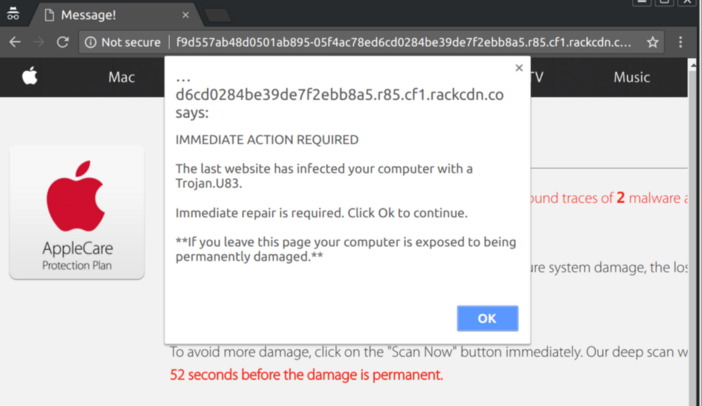

Only in the first case would a Zirconium ad try to hijack the page by abusing web scripting to shove the user into a pitch to download malware or pay for fake tech support.

By Confiant’s estimate, Zirconium would have paid a total of $220,000 to run these ads, for a potential cost per victim (assuming 5% clicked on the malvertising bait instead of closing the browser window) of 8 cents. At that rate, you don’t need to find that many victims to make money.

What you can do: update Chrome

Confiant’s report promises no cures for this but does endorse one treatment: the imminent release of the next version of Google’s Chrome browser, which will block the scripting techniques that forced-redirect ads abuse.

There’s no word on whether Apple (AAPL) and Microsoft (MSFT) will add a similar feature to their own browsers — although if any company would be motivated to do so, you’d think it would be Apple, since it doesn’t make its money from ads.

But even if every browser swiftly deployed the same defenses as Chrome and banished forced-redirect ads to oblivion, that wouldn’t cure ad fraud — a problem that Juniper Research estimated in September that it will cost advertisers $19 billion this year. Until somebody can find a cure for capitalism, you can’t expect to see a web free of scammy, sketchy ads.

More from Rob:

Email Rob at [email protected]; follow him on Twitter at@robpegoraro.

Follow Yahoo Finance on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance