Government should collect wealth data just like income: Berkeley economists

Perhaps more than anything in recent memory, the coronavirus pandemic has illuminated how wide inequality in America has gotten.

The pandemic precipitated one of the worst labor markets in American history, with unemployment breaching the 20% mark, lines at the food bank, and the stress of a pandemic topping it all off. At the same time, it’s been great for the portfolios of the asset-owning classes, who have seen market highs while working from home away from the risk of COVID-19.

However, there’s confusion about exactly how much inequality there is. It’s extremely hard to quantify and the government just doesn’t have enough solid data about its population, even though it passes laws and regulations ostensibly for public benefit.

In fact, private companies have far better data than the government – and they should be the ones tracking individual households’ money, according to Berkeley economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman.

This is one of the key takeaways from Saez and Zucman’s new research paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research.

“We have little patience for the view that ‘inequality is impossible to measure,’” Saez and Zucman write.

In the past, the two French economists, along with their famous colleague Thomas Piketty, have examined inequality in the U.S. and found it has been widening considerably, often thanks to low taxes — as well as tax avoidance and loopholes.

In another recent paper, Zucman and Saez write that “during the 1980–2020 period, wealth as a whole has been growing almost twice as fast as income. The result is that relative to to what is produced and earned in a given year, the wealth of the rich has skyrocketed.”

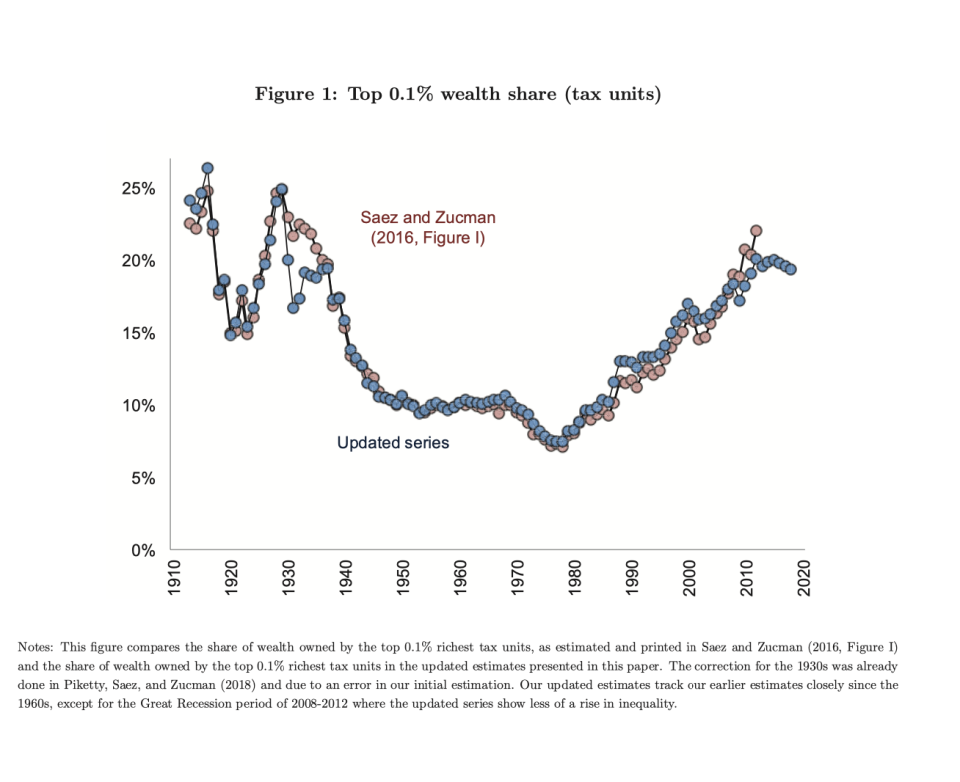

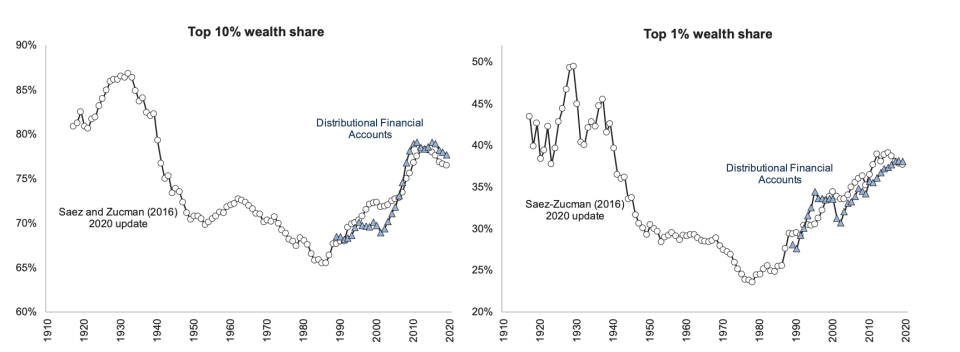

“The top 10% wealthiest tax units owned 77–78% of wealth in 2018, an increase of 10 points since 1989... the top 1% wealthiest tax units owned 38% of wealth in 2018, also an increase of 10 points since 1989,” they write.

Their analysis is thorough, but challenging. Because there is no centralized data on wealth like there is for income, it’s been hard to know for sure how things have evolved. Cobbling together available data from Fed surveys, the IRS, and more, the economists have been measuring it every other year, in 2016, 2018, and now in 2020.

Other academics found evidence that the rate of inequality increases were slowing, which would have been good news and evidence that current policy could be having positive effects.

Saez and Zucman’s recent paper refutes any ideas that the current socio-economic framework was improving — even before COVID-19, which appears nowhere in the paper, though it was published in October.

The government should do this job and understand its citizens’ position

But beyond bringing the picture of American inequality into focus, a key point from Saez and Zucman was that they shouldn’t have to be measuring this.

“There is a growing gap between the richness of individual data collected by corporations (such as Google, Facebook, Visa or Mastercard) for private commercial purposes and the paucity of what is available to governments for public statistical purposes,” the economists write.

These private (publicly-traded) companies have tons of data from consumer transactions and frequently compile profiles on customers that include estimates of wealth via direct or indirect means. For Facebook and Google, their algorithms from the substantial amounts of user data can paint an accurate picture of a person, whereas financial services companies like Visa see information-laden transactions directly.

Saez, Zucman, and Piketty have loudly argued for wealth taxes — Zucman and Saez even helped Sen. Elizabeth Warren develop her wealth tax idea when she ran for the Democratic presidential nomination. Besides as a way to pay for social safety net services, the economists see a wealth tax as an easy way to get better information about household wealth.

The economists don’t see a wealth tax as the only way to get that information. The IRS could have financial institutions send more information besides what interest or capital gains were realized independent of a wealth tax.

“Even without a wealth tax, the tax administration could collect information on assets and debts from third parties (banks, pension funds, brokers, etc.), as is already done for income, and ownership of closely held corporations,” the economists write. “These data could be used to estimate individual wealth—as done in a country like Denmark—and allow for the construction of more accurate Distributional National Accounts.”

Better understanding of how the “accounts” are distributed across the country would improve policies and ultimately outcomes. In the economists’ view, the government should be doing this for the people’s benefit.

—

Ethan Wolff-Mann is a writer at Yahoo Finance focusing on consumer issues, personal finance, retail, airlines, and more. Follow him on Twitter @ewolffmann.

Robinhood investors were a market-stabilization force during the pandemic crash

Why savings accounts have fallen — and some more than others

Intergenerational conflict is getting worse, Deutsche Bank warns

NYU professor: Make sure young investors 'don't become addicted' to online stock trading

Young investors have a huge stomach for risk right now, data suggests