A hacked census would be disastrous for businesses

The 2020 U.S. Census is going digital for the first time ever, a move that is supposed to save money. But innovation brings a new element to the country’s most crucial survey: hacking and disruption.

Last month, the Government Accountability Office put out a report on the 35 “high-risk areas” where the U.S. is lagging, and labeled nine that “need especially focused executive and congressional attention.” Both the 2020 decennial census and general cybersecurity of the country made the list.

“The Bureau has not addressed several security risks,” a following report in April said.

The role of the census goes far beyond allocating representatives to Congress, and any shadows — from hacking or mistrust — cast on a well-executed census could prove disastrous in myriad ways beyond the public sector.

Why good census data is so important

Before getting into the specific risks to the U.S. census, it’s important to understand exactly what it does and why it’s so important.

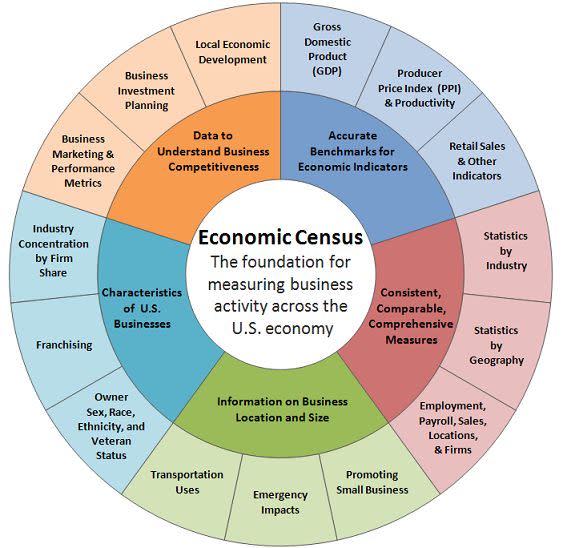

As Brookings demographer William Frey wrote recently, the census is the “backbone of thousands of government and private sector surveys that guide decision-making.” Entire industries rely on accurate and trustworthy census data to function properly.

The U.S. census is not an ordinary survey that samples the population; it literally polls every household in the country and counts every occupant.

When surveys sample, they do so often using census data, which provides the reference point for the sample.

“It’s the framework for any kind of samples taken over the course of the next decade,” Frey told Yahoo Finance in an interview. “It’s all predicated on the census.”

Since the census is the only time when a sample is not used, its accuracy is critical. Businesses use it to see if they will have a labor force and customers; state, local, and federal government agencies use it to see where services are needed, and where to build hospitals and schools, Frey said. The timeframe is also critical, as the data expires.

“I'm a demographer and if it was up to me, we'd have a census every year,” said Frey. “By the time you get 9 years out, that's the worst data you'll ever get.”

Some industries rely on census data more than others, but it touches every facet of the economy, from where to put cellphone towers to how insurers calculate rates. The Census.gov website itself explains real-world uses, from specific businesses to Florida trying to figure out emergency management preparations to plan for major weather events.

“Population density is a rating variable for private-passenger auto insurers, homeowners, renters, and business insurers,” said Michael Barry, head of media and public affairs at the Insurance Information Institute. “Roadways with more cars are going to have more accidents. A hurricane striking a city is going to generate more insured losses than if it were to hit a rural area.”

Rachel Garfield, a senior researcher with Kaiser Family Foundation, told Yahoo Finance that the census “is pivotal in helping health care providers and policymakers understand where people live—and therefore are likely to need/use health care services—as well as basic demographic data that can predict many health care needs.”

In a recent op-ed, Nielsen CEO David Kenny warned that a flawed census would have “significant consequences for American businesses, which rely heavily on census data to make “their most critical business decisions.”

Nielsen, a company that scores of businesses rely on for advertising metrics, the entertainment industry, and more, revises its media markets immediately following the census, which reverberates through the economy, affecting “sometimes billions” of dollars and thousands of jobs, Kenny wrote. “The last thing that business needs is for the next 10 years of data to be built on a faulty foundation,” he said.

Serious security concerns

A digital-first census isn’t happening just because we are well into the 21st century — it’s supposed to cost less than a paper census. But protecting the census isn’t cheap — and could cost even more than was previously thought. It will likely be $15.6 billion.

“It’s a ginormous project the government is taking on,” said Jason Glassberg, co-founder of Casaba Security, who has advised and audited security for large companies like Microsoft. “Is is the government up to the task? They’ve had snafus. The whole HealthCare.gov thing melted down a couple of times, and there’s been a couple of high-profile hacks against government systems.”

In 2015, the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) was hacked, breaching 21.5 million records and in 2013 HealthCare.gov’s rollout experienced myriad technical problems. The Census adds the issues of both and magnifies them. Around 330 million people are set to be counted in the U.S., and one website is to be the portal to make that happen. On the bright side, however, is that the information requested in the census is much less sensitive.

Alex Hamerstone of TrustedSec, whose CEO testified in Congress on the HealthCare.gov mess, noted the importance of preparation, including testing the system under the full load, simulating the size of the population. One big question that stems from the HealthCare.gov troubles: If they felt it wasn't 100% secure, would they put off the census?

Glassberg pointed out that current tests are somewhat head-scratching, at least from an on-the-ground perspective, which is implemented if people fail to answer questions online and then through the mail. The 2018 census test, its “last chance” according to the GAO, used Rhode Island, America’s smallest state, as its proving ground, and encountered problems that need to be addressed.

Hacking, disruption, and doubt

A digital census system will be complex and liable to have some weaker points than others, but the ends should have security.

“If [census counters] are out there with tablets, [hackers] are not going to have the ability to modify a million records,” Hamerstone said. “You have to worry about big databases.”

On that front, however, census data should be safe on Amazon’s GovCloud. If that were to get hacked, Hamerstone said, we would have bigger problems than the census.

It’s the steps in between that security advisors will worry about the most. AI and other advanced technology can sniff-test numbers by flagging houses with 30 people that used to have 5, or numbers that deviate from what is expected from things like vehicle registrations. But again, the question remains whether it works under the load of a 330 million person nation.

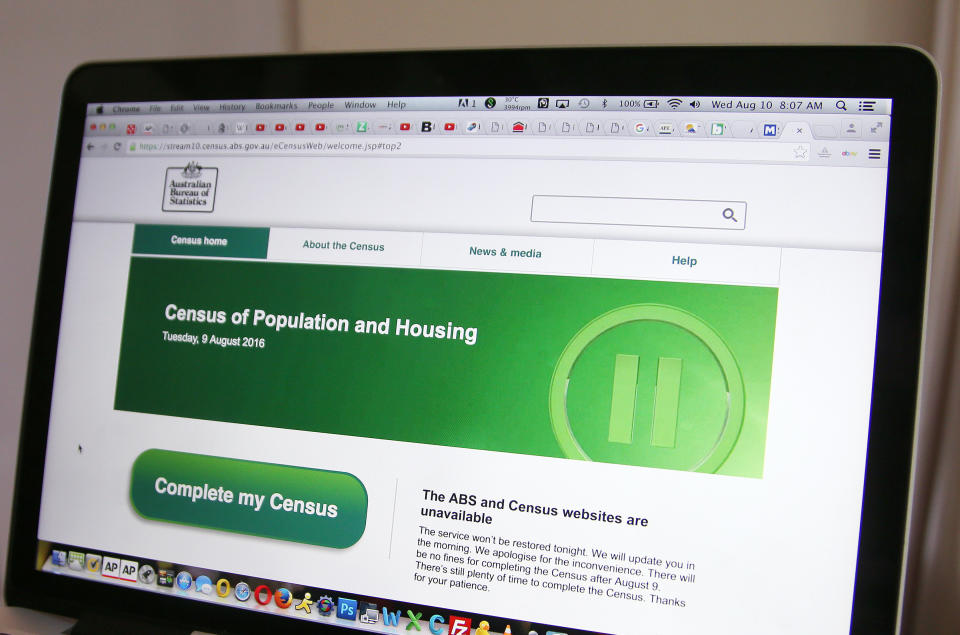

Even if hacking is prevented, preventing people from filling out the census forms may be another issue. When Australia did its census digitally in 2016, the website shut down and the country’s census bureau said it had suffered denial-of-service attacks. The country managed to move through it with a successful census, but the issue showed an extremely disruptive digital weakness to be exploited.

Another potential issue: domain names that are similar enough to the census to trick less internet savvy people.

“Anytime there is an electronic system, everyone uses it as a scam pretense,” said Hammerstone. Though the Bureau has purchased about 100 domain names, that may not be enough. “It’s like plugging a dam with 1000 holes with 10 fingers.”

Hacking and scams are just smaller issues to the largest, which can occur even in a successful census: the sowing of doubt.

“You don’t have to do the active naughtiness,” said Glassberg. “The mere threat can be enough to cause the data to be in question. Do the Russians or Chinese have to do anything or do they need to make unsubtle murmurs on social media?”

This could be done before, or after. Before could mean that people decide not to trust the system and decline to participate, which would taint the census and start a chain of doubt trickling from the government down to the private sector that piggybacks on this data to make decisions. After wouldn’t be quite as bad but every number would have an implicit asterisk and a similar chain of doubt.

The citizenship question and post mortem

On top of the hacking, what is normally a nonpolitical census has been roiled by the Trump administration’s desire to put a question asking about citizenship status, something that many experts on both sides of the aisle see as a potential vector for tainted data. Since 1950, the Decennial Census has not had a citizenship question; instead 3.5 million households get another survey at the same time that is more in depth, called the American Community Survey.

Thirty states have sued the Commerce Department to keep this question out, and the Supreme Court heard arguments on April 23 about whether to leave it in. The conservative majority of the court appears to be leaning towards allowing the question.

If undercounting does occur, one problem is that it might take a few years to find out. In the years following a census, the Bureau does a post-census enumeration survey, where they go back into neighborhoods and check their work.

“It’s a sample, of course, but it does give them some kind of sense — a good one — of undercount and overcount,” said Frey. “They would learn about that, for sure, two or three years after the census is done.”

-

Ethan Wolff-Mann is a writer at Yahoo Finance focusing on consumer issues, personal finance, retail, airlines, and more. Follow him on Twitter @ewolffmann.

Congress may ban the IRS from launching free online tax filing