A bill aimed at Facebook's bogus political ads has some big problems

“Honest Ads” may sound like a contradiction, but a bill by that name aims to force some truth into online political marketing.

It wouldn’t require the ads themselves to tell the truth (that’s crazy talk!). But it would require disclosure of who paid for them and, at least as important, who they targeted.

This bipartisan bill is both a belated response to the bout of covert Russian messaging that swept over social networks before last year’s election and an attempt to stop a rerun of that strategy in the 2018 midterms.

But it might not stop other issues, like vaguer appeals to ethnic or religious prejudice or social-media campaigns that don’t rely on paid ads.

An old rule in a new environment

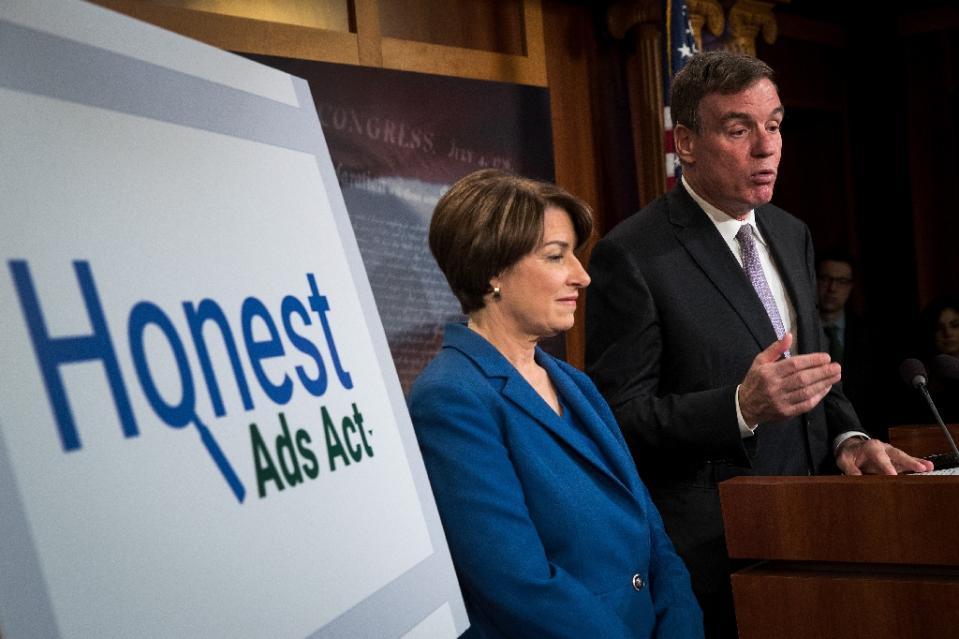

The Honest Ads Act (S. 1989), introduced Oct. 19 by Sens. Amy Klobuchar (D.-Minn.), Mark Warner (D.-Va.), and John McCain (R.-Ariz.), would essentially extend longstanding rules for radio and TV political ads to most of the online world.

Just as those offline spots must identify who paid for them (“I’m Rob Pegoraro, and I approve this message.”), this bill and a companion House measure (H.R. 4077) introduced by Reps. Derek Kilmer (D.-Wash.) and Rep. Mike Coffman would demand the same “clear and conspicuous” disclosures.

But the Honest Ads Act would also require any site with more than 50 million monthly U.S. users — yes, this one included — to document all political ads purchased by anybody spending more than $500 a year on “electioneering communication.”

Those records would include the audience targeted by each ad and how many people saw it. And these online platforms would have to make them “available for online public inspection in machine readable format.”

The intended result: forced publicity for “dark posts” that aim to persuade highly specific audiences but which never appear to everybody else.

Those were a frequent tactic of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, but the president has yet to share his take on the bill.

“You have to start somewhere,” said Alexander Howard, deputy director of the Sunlight Foundation, a pro-transparency group that worked with the bill’s sponsors. “This starts somewhere.”

What it won’t or can’t do

But what’s a political ad? The Honest Ads Act keeps the current definition: “a message relating to any political matter of national importance,” which can cover a candidate, an election or “a national legislative issue of public importance.”

State-specific messages might not count, and neither could vague appeals to ethnic or religious ties or blood-and-soil nationalism.

“It leaves some room for interpretation,” Howard said. “The biggest question there is the FEC’s ability to have a credible enforcement action.”

The Federal Election Commission hasn’t exactly been the most assertive office. It ran up frequent 3-3 tie votes before having one of its six seats go vacant; now all five of the remaining commissioners are serving on expired terms.

And as the explanatory text of the bill admits, Russian interference in the election went well beyond $100,000 or so spent on Facebook (FB) ads. It included such ad-free operations as fake accounts on that social network and bots on Twitter (TWTR).

For instance, the bill wouldn’t ban efforts like the fake “Heart of Texas” Facebook page that bamboozled a quarter of a million users into following it. Facebook itself has stepped up efforts to combat fake accounts — but it also has a history of being shocked, shocked that people would game its system.

“It’s important to just understand it as a loophole-closing bill and not a comprehensive election-interference management bill,” said David Carroll, a media professor at the Parsons School of Design who’s running a crowdfunded legal campaign to force the disclosure of voter data collected for the Trump campaign.

Online ads in general are a mess

Industry responses have mostly followed a traditional template: Don’t worry, we’ve already got this.

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg said Sept. 21 that it would require political advertisers to reveal their identity, then let users see every ad run by a political page even if it didn’t target them. The site has since announced plans to step up its scrutiny of ads and advertisers.

On Tuesday, Twitter went a step beyond by announcing that it would label political ads with a purple tag and disclose their purchaser and “targeting demographics.” The social network will also set up a database of all of the active ads, which users can inspect.

Thursday, the company also said it was booting all ads for the Russian propaganda outlets RT and Sputnik and would donate the $1.9 million it’s earned in RT ads since 2011 to outside research on Twitter’s utility as a tool to persuade populations.

At a House subcommittee hearing Tuesday, Interactive Advertising Bureau CEO Randall Rothenberg made a case for the ad industry’s self-regulatory efforts.

Google (GOOG, GOOGL), Snapchat (SNAP) and Pinterest, however, have yet to make their own announcements on this issue.

Meanwhile, the rot in online ads isn’t confined to mysterious political pushes. Ad fraud has become a massive problem — Juniper Research projects it will hit $19 billion in losses worldwide in 2018.

“It’s unequivocal that we have a trust problem in digital advertising on a variety of fronts,” e-mailed Jason Kint, CEO of the publishing group Digital Content Next.

“I’m not sure why we don’t consider these requirements for all paid promotions,” said Carroll, citing the Federal Trade Commission’s longstanding truth-in-advertising rules. “it would potentially improve the quality of the whole marketplace.”

The Honest Ads Act ought to spark more conversation about that broader problem. But first, Congress has to do something out of character and not let yet another tech-policy measure die in committee.

More from Rob:

Why the Feds want to make it easier for them to get into your phone

Why Equifax needs to give up some details about how it got hacked

Email Rob at [email protected]; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.