How to make money in stocks this year ... and beyond

The market has been going nuts lately — up 29% last year — and stocks are at record highs.

There’s no way you should be buying now, right?

Wrong.

I know this sounds insane, but here’s the plain truth: You should always be buying. Even now. Even with the market see-sawing like crazy on the first two trading days of 2020 — up on Thursday with China news and down on Friday with Iran news.

And unless you have a big lump sum to invest (more on that happy dilemma later), the best way to buy — and this may be familiar, but bear with me — is through dollar cost averaging, which simply means buying a set amount of stock, say every month, come hell or highwater or market top. The math just works.

Now the reasons why it’s important to delve into dollar cost averaging (or DCA) right now are two-fold. One, many of us know about DCA but don’t do it, so let this serve as a reminder! And two, there are actually a number of nuances and misconceptions here to explore and dispel.

Don’t try to time the market

Like most who have studied DCA, Dr. Karyl Leggio, professor of finance at Loyola University Maryland, Sellinger School of Business, will tell you that if you have a big lump sum, you should invest it right away. But she says DCA is important, as well.

“The value of dollar cost averaging is the discipline of continually putting money into the market,” she says. “The reality is you aren’t able to time the market. If you look down and say the market is at record highs, I won’t put money in the market now. Over time you miss more opportunities than you save by trying to time the market.”

Buying either at market tops or bottoms is scary. Also, few people have consistently been successful at timing those market tops and bottoms. But counterintuitive as it may sound, you need to ignore the noise and invest right through all of it.

The best strategy is to set up an automatic investing plan — go to any broker dealer’s website — and put $200, $500, $1000, or whatever you can afford, every week or month, into a low-cost, broad-based index fund, like the Vanguard 500 Index Fund. Just set it and forget it. Now you’re dollar cost averaging. Your money will buy you fewer shares when the market’s up, and more when it’s down, giving you an average cost basis. This is instead of you bunching money up and trying to time the market.

DCA is essentially aligned with 1) Warren Buffett’s notions that investing in the stock market is your best bet and that compounding (through stock dividends) is the investor’s best friend. And 2), the fact that stocks usually go up. “As long as you believe in the fundamentals of the U.S. economy, you should invest over time. DCA has that benefit of discipline, of constantly putting money in the market,” Leggio says.

Powerful stuff that.

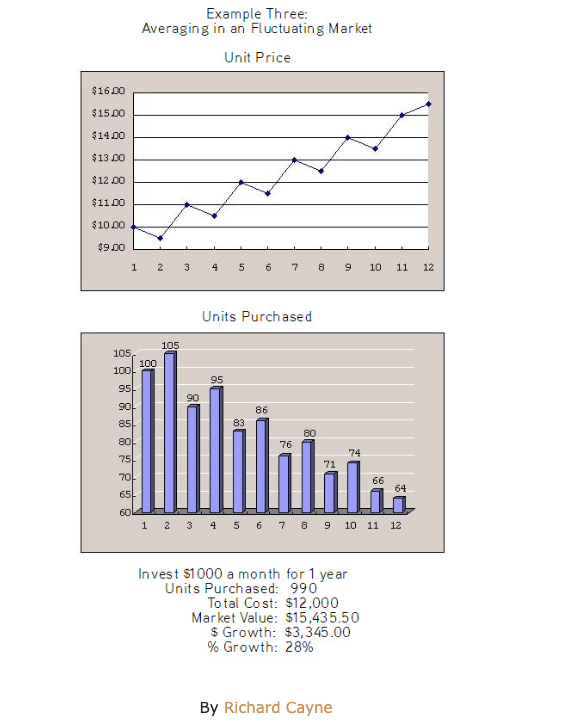

This is a cool graphic representation of how DCA works in a fluctuating market.

Dollar cost averaging even makes sense if you start out at the worst possible time. You just need to hang in there.

Here’s a neat case study from Business Insider’s Andy Kiersz where he had a hypothetical investor put $50 into the market every month starting right at the pre-crisis peak in 2007 and as it tanked in October 2008. For months this was tantamount to throwing cash out the window, as the market slumped lower and lower, finally bottoming out in March of 2009. Buying stocks back then took great fortitude, although remember Warren Buffett did.

But the hypothetical investor kept buying, and BI reported that six years later, “the value of our investor's portfolio as of January 2014 is $5631.87. If they instead had taken their $50 each month and held it as cash, they would have just $3800.”

The article also notes that: “...everyone is worrying that we are at or near a market peak. And this has investors extremely hesitant to buy stocks for fear of a big decline or perhaps a crash.” (Remember this is 2014!) Of course, “everyone” was wrong. Imagine if you had listened to the worrywarts and not bought over the past five years, or even worse, sold!

The DCA naysayers are getting it wrong

There are those who pooh-pooh DCA. Sometimes they are shills for active money managers or brokers who have a vested interest in selling you advice and/or wish to seduce you into the world of churn and high-priced commissions. Still, let’s address the naysayers.

Take this sentence from the Wikipedia page on dollar cost averaging (it’s under the heading, “Confusion,” btw): “If the market is expected to trend upwards over time, DCA can conversely be expected to face a statistical headwind…”

Eh, confusion indeed. The problem with that sentence of course is that no one knows when or how long the market will “trend upwards,” or downwards for that matter. So the “statistical headwind,” is a moot point.

There are also those who might think that DCA doesn’t work as well as simply waiting and buying the dip, (BTD.)

Wrong again.

Even if you knew when the dips would occur, you wouldn’t fare as well as dollar cost averaging, or so stipulates Nick Maggiulli, an analytics manager for Ritholtz Wealth Management and writer at “Of Dollars and Data,” in this note. The headline of the piece says it all: “Even God couldn’t Beat Dollar Cost Averaging.”

Maggiulli hypothetically invested $100 every month for 40 years between 1920 and 1979 and compared to buying at the exact market bottoms during the same time period. While buying the dip worked well in the 1930s — because of the magnitude of the Great Crash, the market was down over 80% — over time DCA beat BTD 70% of the time. And this is ignoring DCA’s set-it-and-forget-it, peace-of-mind advantages, never mind “the God factor,” i.e., calling the exact market bottoms, which of course is impossible. Miss the bottom by just two months, Maggiulli reports, and DCA beats BTD 98% of the time.

Pretty convincing, I’d say.

Making sure to look long-term is important too. Here’s an example, where an analyst compares three investment strategies; DCA, investing randomly, and investing a lump sum. In this particular horse race, DCA comes in last place. The problem is it’s only over 12 months — and in an up market! A one-year time period proves nothing. You might as well throw darts.

It’s true that when you have a large lump sum to invest, DCA doesn’t make sense. Think about it. Say Uncle Warbucks leaves you $5 million and you decide to invest $5,000 a month. Not smart. That would take you 83 years to complete. You’d miss out on a lifetime of gains.

With a big chunk like that you are better off just shutting your eyes and plunging into the market knowing you might be heading smack into a bear market. How bad could that be? According to Investopedia, since 1926, there have been eight bear markets, ranging in length from six months to 2.8 years, and in severity from an 83.4% drop in the S&P 500 — the Great Crash I mentioned earlier — to a decline of 21.8%.

Bottom line: Dollar cost averaging is the way to go when you have a limited amount of investable capital available each month to take out of your paycheck. In other words it’s for most of us, most of the time.

Looking at today’s sky high stock market, there’s no doubt that at some point, stocks will decline for a prolonged period. And you should be buying. Before, during, and after.

Get the Morning Brief sent directly to your inbox every Monday to Friday by 6:30 a.m. ET. Subscribe

Andy Serwer is editor-in-chief of Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter: @serwer.

Read more:

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, LinkedIn, and reddit.