How a new financing model could fix America’s broken student loan system

Yahoo Finance reporter Brian Cheung contributed data to this article.

News reports of jaw-dropping scandals involving corruption and fraud in the admissions process of several elite schools are coming at a bad time for the higher education community. Academia was already playing defense in Washington against perceptions of favoritism in admissions practices and intolerance for diverse political views.

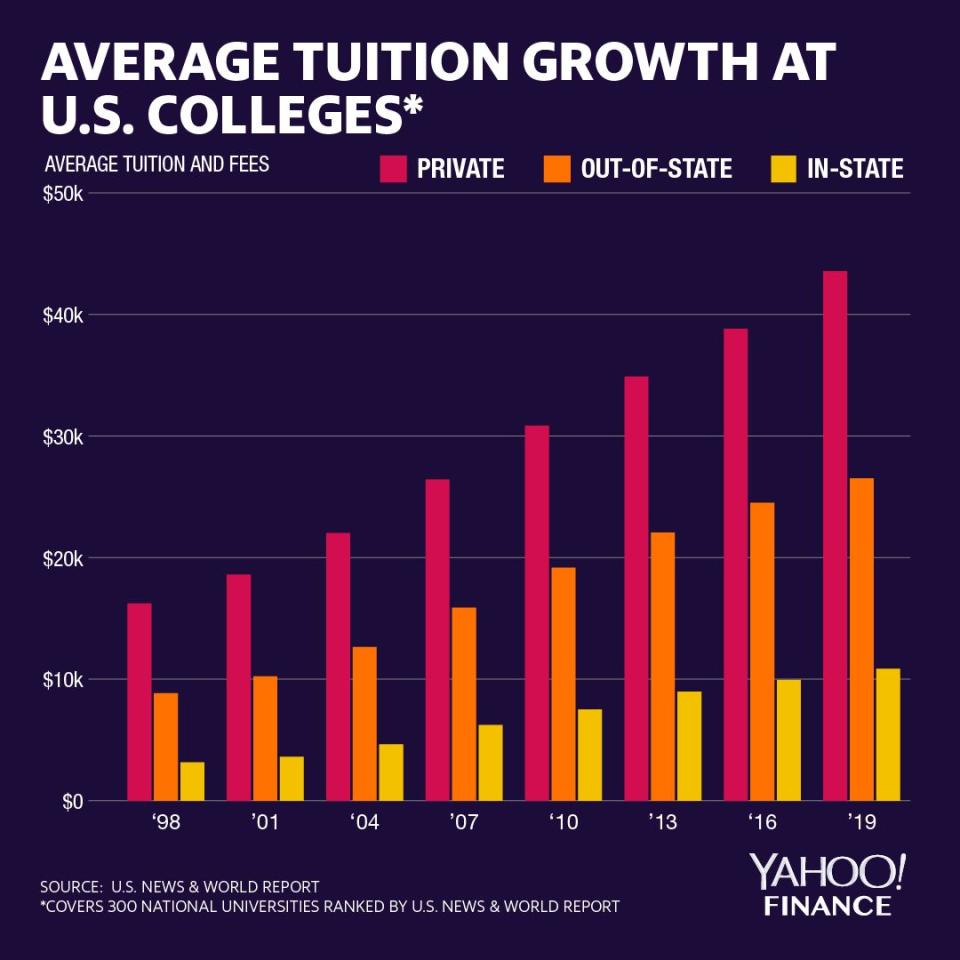

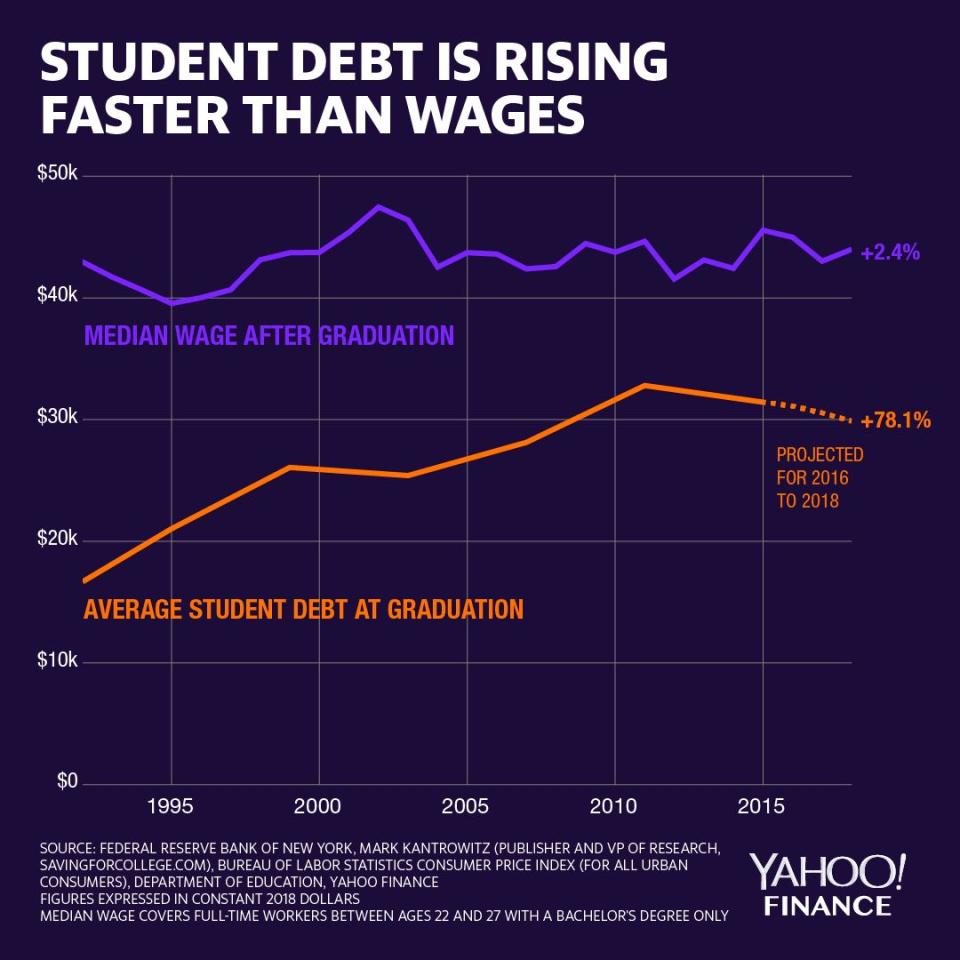

But perhaps most damaging has been widespread public concern over high college costs and the $1.4 trillion in taxpayer-backed debt students have racked up to pay for them.

Proposals have already been circulating Congress to tighten the student loan program and impose more accountability on colleges for poor student outcomes. And just last week, the Trump administration proposed new caps on student loans. Higher education’s value is being challenged as never before: Are colleges singularly focused on providing students with a good quality education, or is that secondary to maximizing tuition revenue and building networks of elite donors? We tend to think the former and that the vast majority of colleges put the interests of their students first.

An experimental new financing model

However, they need to acknowledge the status quo isn’t working. Instead of digging in and opposing such efforts, higher education should work collaboratively with Congress to fix our broken system of higher education finance. There are two core problems with that system: 1) it relies primarily on debt to finance college even though it is impossible to know the eventual repayment capacity of a young person just entering school; and 2) it creates misaligned economic incentives by placing all the financial risks on students, and ultimately taxpayers if the student defaults, while loan proceeds go to higher education institutions, who suffer no financial consequences if their students fail.

Fortunately, some innovative colleges, in partnership with private investors and a small number of philanthropies, are experimenting with a new financing model called “income share agreements” or “ISAs” which address these two core issues. With an ISA, instead of assuming a fixed debt obligation, students simply agree to pay an affordable percentage of their future income over a set time period, subject to an overall cap. High earners will have larger payments than low earners, but all will have an affordable payment, based on what they will actually be making. Importantly, when the college is providing some or all of the funding for the ISA, its return will be aligned with its students’ post-college earnings, giving it economic incentives to make sure its students both graduate and find jobs. The college is, literally, invested in its students’ success.

ISAs should not be confused with current income-based repayment plans or IBRs offered by the government, which retain students’ debt obligations and can actually lead to increased debt for low earners when their income cannot support interest due on their loans. With ISAs, there is no principal or interest. Thus, they are much better suited for low income students as their financial obligations never exceed their ability to pay.

In a recent paper commissioned by the Manhattan Institute, we looked at the small but growing number of colleges and universities offering ISA programs. Indiana’s Purdue University launched the first such program in 2016. About a dozen other institutions have now followed suit, including Lackawanna College in Pennsylvania, Clarkson University in New York, and the University of Utah. Most of these pioneers offer ISAs to students as an alternative to non-subsidized federal loans, though a few are offering them as a complete substitute for borrowing. They are also offered to students who do not qualify for federal loans, such as noncitizen “DREAMers.” In addition, they are popular with students pursuing alternatives to traditional higher education such as computer coding academies, which are ineligible for federal student loan programs.

A common feature of all these ISA programs is that they require payments only when the graduate meets a certain income threshold. All impose time limits and caps on the total amount that needs to be repaid, though they differ widely in where they set those caps and limits. A few, such as Purdue, vary terms according to major, providing somewhat more favorable terms to high-earning majors to mitigate “adverse selection” or the risk that only low-earners will participate in ISAs. Adverse selection is a concern commonly raised about ISAs, though notably, most colleges offering them have decided not to differentiate among majors. The insurance feature of ISAs, providing downside protection if the high-earner suffers a setback through, for instance, illness or economic conditions, as well as caps that place an upper-bound on the high-earner’s total obligation, help address adverse selection, but the differing terms of these early programs will help test that hypothesis.

More universities need to get on board

Though ISAs are a promising alternative to student debt, we need more schools willing to offer them. One impediment has been the low level of philanthropic support. Most foundations and college endowments have taken a wait and see posture, preferring to let private capital take the lead. Though private investors may have a place in helping colleges fund ISAs, they may be less patient and less prone to experimentation than nonprofits that will not be as focused on near-term investment returns. Greater support from philanthropy would give colleges more flexibility to experiment with contracts that meet the needs of students pursuing a variety of disciplines, for instance, by providing longer repayment periods for liberal arts majors who tend to hit peak earnings later in their careers.

Another impediment to ISAs has been the lack of a clear legal framework. While ISAs are legally permissible under current law, private investors and philanthropies are hesitant to invest in an innovation which has no explicit rules governing student protections, regulatory oversight, and enforceability. Bipartisan legislation has been introduced to provide such a framework, which includes caps on the percentage of income which can be dedicated to ISA payments, student contractual rights, and oversight by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Enacting such legislation would help spur greater ISA availability at no cost to the taxpayer.

Most importantly, the government could be more pro-active. Though nascent ISA programs are now offered primarily as alternatives to high-cost bank and PLUS loans, they hold promise as an eventual replacement for direct federal lending. Still, more testing is needed to inform the design of such a program. Congress could instruct the Department of Education to fund a small number of ISA pilots, for instance, with colleges and the government sharing in the funding of ISAs and likewise, sharing in ISA returns. Unlike student loans, which place the financial risk squarely on students and taxpayers, ISA partnerships would have colleges and the government sharing in the risk of student failure and rewards from student success. This would be an elegant, dynamic way to encourage colleges to focus on their students’ post-graduation employability, without Uncle Sam trying to guess labor market needs and micro manage students’ career choices in providing federal student aid.

A political backlash is brewing against higher education. The last Congress brought punitive tax measures targeting large college endowments and the deductibility of interest on student debt. In this Congress, higher-ed will again be in the cross-hairs. Institutions of higher learning would be well-advised to follow the lead of this small group of ISA innovators and demonstrate to the Congress that they are ready to take on greater stewardship for students’ success. We are failing young people, failing taxpayers, and failing our economy which needs more highly educated workers to remain globally competitive. Our system of college finance is taking on water. ISAs may be able to keep the system afloat.

Preston Cooper is a research analyst with the American Enterprise Institute. Sheila Bair is the former Chair of the FDIC and former President of Washington College.

Read more:

The $1.4 trillion federal student loan market has a huge issue — transparency

Elizabeth Warren wants a banking system that works for everyone