Income share agreements: Assessing the latest big idea for fixing the U.S. student loan crisis

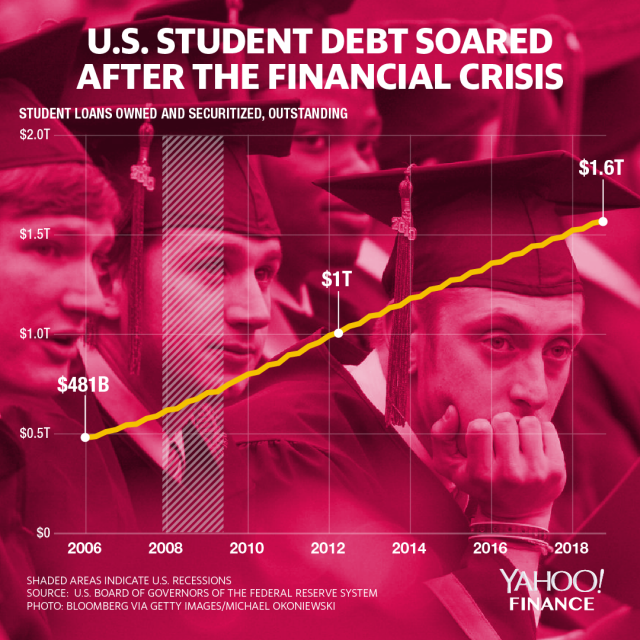

The American student loan system — described by former officials as “an abomination” and a “trillion-dollar black hole” — currently includes 44 million borrowers holding $1.6 trillion in debt amid a pandemic and an economic crisis.

One of the solutions being floated involves income-share agreements (ISAs), a type of financing where a student pays for education by paying a percentage of their income after graduation.

“Over the last several years, we've certainly seen a resurgence and the interest in using income-share agreements to finance higher education, and potentially for other uses as well,” Joanna Darcus, a staff attorney at the National Consumer Law Center, told Yahoo Finance. “And that the interest is primarily driven by financial companies, FinTech platforms, venture capitalists, and some institutions who are interested in exploring the model.”

While not a new idea, politicians and experts are currently debating the pros and cons of ISAs.

Are ISAs ‘exploitative’ or ‘promising’?

In June 2019, after an Education Department (ED) official revealed that the Trump administration was considering a federal ISA program, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) joined Reps. Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) and Katie Porter (D-CA) in writing a letter to ED Secretary Betsy DeVos.

“Like private student loans and many other types of debt, the terms of an ISA contract can be predatory and dangerous for students,” they argued. “ISAs also include some of the most exploitative terms in the private student loan industry, including mandatory arbitration agreements and class action bans. Unlike private student loans, however, these risky contracts have virtually no transparency and have experienced little to no oversight from federal regulators.”

The following month, Sen. Todd Young (R-IN) introduced the ‘ISA Student Protection Act of 2019’ and described ISAs as a “debt-free” option for those seeking financing for their higher education.

“Income-share agreements are a promising way to finance postsecondary education and an attractive alternative to private student loans and PLUS loans,” Senator Mark Warner (D-VA) stated in support for the bipartisan bill. “ISAs are also proving to be uniquely responsive to the needs of students who are ineligible for existing federal student aid programs — including DACA recipients … and those attending short-term training programs.”

In December, former ED appointee Clare McCann highlighted a presentation by the department, detailing ISAs as a policy option. And a December op-ed by the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board applauded the first major college to try ISAs, Purdue University.

“The beauty of income sharing is that students don’t leave with a debt that is accruing interest even as they struggle to pay it back,” the WSJ stated. “If they don’t find a job, the program gets no money back. This alone is an improvement over the traditional student loan because it aligns the students’ interests with those of their universities.”

In a Washington Post op-ed, Purdue President Mitch Daniels stated that “ISAs have emerged principally in response to the wreckage of the federal student debt system” and argued that an ISA is “dramatically more student-friendly than a loan.”

At the same time, Daniels stressed that Purdue would “never recommend an ISA in lieu of taxpayer-subsidized federal loans — you can’t beat their artificially low rates — but compared with higher-interest private loans or federal ‘parent-plus’ loans, they are often far preferable.”

Seton Hall University Associate Professor Robert Kelchen agreed with the notion that ISAs could serve as an alternative to private student loans.

“The big reason why I'm open to ISAs is … if the alternative is getting a traditional private loan or even a Parent PLUS loan with the federal government, those loans don't have protections built in if you have a low income,” Kelchen told Yahoo Finance. “I don't support ISAs replacing traditional federal student loans that have those protections. But it's at least worth considering for someone who very well may not be able to access private loans, because they don't have credit.”

Evolution of ISAs and how they work today

ISAs aren’t an entirely new concept.

The first big experiment with ISAs was in the 1970s when Yale University created a “Tuition Postponement Option.” The program was created in 1971 but suffered from “several design flaws” and was discontinued in 1978.

The biggest issue was that participants in the program were grouped into “cohorts” where all members of that cohort would keep paying until the entire group’s debt was paid off. When participants defaulted, the burden carried on, and other members were on the hook. Those who had the means bought out of the program early — paying 150% of what was borrowed, plus interest — leaving lower-income members stuck with the bill. (Yale ended up partially bailing out those students.)

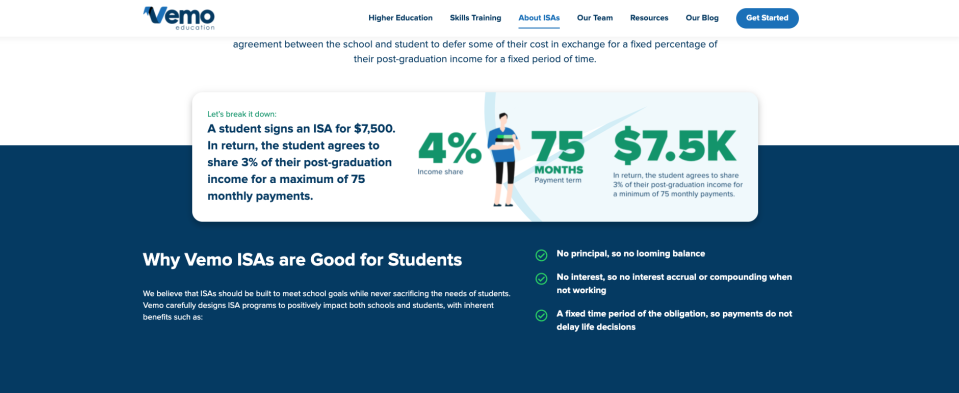

The new breed of ISAs is slightly different, and the basic premise is more straightforward.

“In exchange for X cash today, I promise to pay you Y% of my salary for Z period of time,” David Klein, CEO and co-founder of student loan refinancing company CommonBond, which considered getting into the business around the time the company launched in 2011, explained in a November 2019 conversation. “And to be clear, Z is a defined term. So whenever somebody goes into an ISA, Z is absolutely defined, so it will not and would not be indefinite — it would be very specific.”

Colleges students regularly take out loans to cover the cost of tuition, fees, and other expenses. An ISA would be an alternative to a federal or private student loan where the student promises to pay a portion of their income — a set percentage — for a number of years until they pay that amount back.

The terms of an ISA that a student takes out with their university depends largely on their major and projected future earnings.

According to Purdue’s calculator, a student with a bachelor’s degree in Mathematics who has accepted an ISA of $10,000 would be expected to pay back an annual rate of 3.03% of their future income over 96 months upon graduation in July 2020 and finding a job.

A student with a degree in English who accepted the same amount, meanwhile, would be expected to pay back an annual rate of 4.01% of their future income over 116 months, upon graduation in July 2020 and finding a job.

Purdue developed the ISA program with Vemo Education, a for-profit startup that “designs, implements, and sustains income share agreement programs for universities and alternative education providers across the country.” While Vemo helped create the terms, the school makes the decisions on who qualifies for an ISA.

“We're going to a college and we're saying, ‘How can we help you increase access, mobility, or opportunity for a set of students who you think are underserved right now at your school?’” Tonio DeSorrento, CEO and co-founder of Vemo Education, told Yahoo Finance. “We design an income share agreement program for the college, and then the college develops the income share agreements.”

DeSorrento added there were three big factors that go into determining how much a graduate of that college makes: where the graduates were likely to work geographically, the expected time for graduation, and what the specific field of study is.

Purdue now has more than 1,200 funding contracts issued to more than 760 students — totaling $13.9 million in funding since inception in 2016. The average contract each academic year amounts to around $11,600. No students have paid off their obligation at this point as the contracts typically run for 10 years.

Two major colleges have adopted ISAs: Purdue University and the University of Utah in January 2019. The option is also offered by some smaller colleges, as well as coding bootcamps, including Lamda School and General Assembly.

And there are other companies that offer what Vemo did for Purdue. Nuntiux, an ISA startup that launched in January 2019, sells a different approach involving the student setting the percentage of income and time period for paying back the loan.

Students “define the duration of time,” Nuntiux Founder Oz Waknin told Yahoo Finance. “It ranges, all the way from 1% for one year... and it goes all the way to 20 years, and 15%.”

Interestingly, schools offering ISAs stress that they’re not offering loans: Purdue, for example, insists on its website that the ISAs are “not a loan. It's not a grant. It's something new and different.” Some experts, however, are skeptical of the implications of that language.

“One of the many things that comes up in this context is: How does this differ from existing consumer financial products? Is it a loan? Is it credit? Is it debt?” Tariq Habash, head of investigations at the Student Borrower Protection Center, told Yahoo Finance. “And I think we often hear the industry claim that income share agreements are different from traditional loans, so the rules shouldn't apply. That's just not the case. Borrowers are entitled to the same rights and protections that they are guaranteed with all credit products.”

Other experts and consumer advocates raised other potential issues with ISAs.

Inaccurate salary estimates?

One of the red flags about ISAs are the salary estimates, higher education experts say.

The Century Foundation’s Jen Mishory wrote last year that the salary assumptions made by Purdue’s ISA calculator sometimes underestimated students’ reported earnings derived from survey data. When compared side-by-side with Purdue’s survey data on what recent graduates are actually making, the salary estimate in the calculator is far less for some.

This assumption then makes the cost of an ISA loan “appear cheaper,” Mishory noted, meaning that borrowers may be misled by advertised costs that are not accurate.

On June 1, the Student Borrower Protection Center and the National Consumer Law Center filed a complaint to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) arguing that Vemo was marketing and promoting ISAs deceptively.

“Vemo lured students by overstating the cost of student loans made by the federal government while understating the cost of its ISAs,” Habash stated in a press release. “Vemo engaged in a deceptive marketing scheme that is predatory and dangerous to students in order to pad its investors’ pockets. Regulators must step in to put a stop to Vemo’s abuses.”

Vemo Co-Founder Jeff Weinstein responded that graduation outcomes based on schools’ data on their current student body is “more up-to-date than the cohort data” from the Department of Education, as the latter “typically lags by 2 to 3 years.”

“ISAs are, in many respects, fundamentally different from loans, so comparing the two is not always straightforward,” Weinstein said in a statement. “We work continuously to improve our Comparison Tool to ensure that it is as clear and accurate as possible.”

Gender and racial bias?

Another other big issue raised by experts is the possibility of gender and race discrimination showing up in the cost of ISAs.

"The way that ISA loans terms are structured means a student’s total repayment amount can vary widely depending on which major they choose, opening the door for disparate impact on students according to gender, race, and ethnicity," Mishory wrote.

Since college majors are highly stratified, “if you base the cost of the ISA loan on major, you may end up with de facto discrimination,” Mishory told Yahoo Finance.

For example, based on a review of data from the University of Utah’s ISA loan program she conducted in 2019, Mishory found that students in the top three female-dominant fields — elementary education, special education, and nursing — would end up paying over $1,000 extra to fund a $10,000 loan as compared to students in the top 3 male-dominant fields of electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, and computer science. (The discrepancy stems primarily from the estimated future earnings potential of the student.)

“As a lawyer who focuses on consumer protection and how broken systems can really hurt low-income consumers,” Darcus of the National Consumer Law Center said when asked about Mishory’s findings, “we are always deeply concerned by innovations that would take advantage of people who are just trying to pursue a degree or get the kind of education that would help them support their families and pursue their dreams.”

‘This is currently a black box that students are signing on to’

Experts also raised potential issues related to interest rates and terms of ISAs.

Mark Kantrowitz, the publisher of Savingforcollege.com, who examined the interest rates for some of the ISA programs, found that the cost/benefit analysis for some students would be turn out worse when compared to more traditional student loan arrangements.

“I’m particularly concerned that they may be much more expensive than student loans and that some caps may be based on a multiple of income as opposed to the amount received,” Kantrowitz told Yahoo Finance.

Klein, the Commonbond CEO, explained that if a borrower has confidence in their future earnings when a borrower is presented with the option of borrowing traditional student debt or taking out an ISA, then the traditional loan would make more sense to avoid “paying what would likely be a higher percentage of your salary over time.” (Conversely, if a borrower has low confidence in their future earnings, they might be more likely to take out an ISA.)

And on the regulation front, Darcus and Habash both noted that the ISA industry was lobbying for troubling new rules that would reduce oversight even further.

“We have an existing consumer protection framework at the state and at the federal level that applies to income-share agreements, just as it applies to other kinds of consumer financial products,” Darcus said. “The industry's asking for carve outs that they don't deserve, carve outs that would give them their competitive advantages over other products like traditional private student loans. That special treatment would be undeserved and unwarranted and would leave consumers open to risks unnecessarily.”

Habash concurred: “This is currently a black box that students are signing on to.”

Ultimately, Kantrowitz concluded, “we do not yet have enough data on how modern ISAs work in practice to evaluate the impact on borrowers.”

—

Aarthi is a reporter for Yahoo Finance covering student debt and higher education. If you are on an income share agreement for your bachelor’s or master’s degree and would like to talk about your experience, reach out to her at [email protected].

READ MORE:

'Inexcusable blunder': Senate Democrats demand action against Great Lakes for credit score mishap

Elite colleges are not going to be easier to get into even after the coronavirus pandemic

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn,YouTube, and reddit.