'It's an arms race': Inside the war on robocalls

I got a call from an unknown number this week. I always send them to voicemail, where they leave me “an important message” about how they can lower my APR or get me an amazing business loan.

But this one was different. It was a real person and he said, “you called me!”

I was confused. I hadn’t called him, but I’ve written about the plague of robocalling enough to know that a spammer must have spoofed my caller ID when they called him. (Spoofing is when someone calls you using a number that looks familiar but is actually fake.) I called him back and we talked about it for a moment. He said he had called “me” back because he thought it might be important given our numbers had the same area code.

Robocalls have always been annoying, but this felt like it had crossed a line by impersonating me through my number.

This happens a lot. According to data communications firm Transaction Network Services, one in 4,000 people will have their number hijacked by robocallers, which leaves many of them feeling like they have to change their numbers.

Because of all of this madness, fewer people are answering unknown numbers. The phone has just cried wolf too many times.

Add-on anti-spam tools from companies like Nomorobo or YouMail or the other 80-plus apps and tools may work well for some people. And businesses are rolling out a special caller ID with more information. But anyone who owns a phone awaits the day when a full, automatic network-based solution will stop annoying calls.

The big question: when is this finally going to happen?

First off, it could be a whole lot worse

“There’s not now or will ever be a single silver bullet solution to this problem,” says Kevin Rupy, vice president of law and policy at USTelecom. One of Rupy’s big tasks these days at the trade group is essentially to fight robocalls. In his spare time, he has a group that helps phone providers trace back illegal callers and refers them to the FCC for fines.

Though it may not seem like it, carriers, industry groups, the FCC, and the FTC are making a difference. As Rupy puts it, “It’s an arms race.” We may be getting more and more irritating trash calls, but a higher percentage is being blocked as the industry evolves and adapts.

Various different spam identification and blocking technologies are in place across the industry at different levels, often in partnership with specialized companies that can closely track the shifts.

“I think what’s really important is that a lot of voice providers are now partnering with these app service providers to deploy these services not at the consumer level [like apps you can download] but at the network level, by the carrier embedding these services with their offerings,” Rupy says. AT&T, T-Mobile, and Verizon, for example, all partner with services that help label and/or block spam calls, like Hiya, First Orion, and Sequint.

A portion of the industry’s power has come from the government’s newfound priorities. In November 2017, the FCC under Chairman Ajit Pai, who has made fighting robocalls his mission, gave phone companies permission to block four types of calls.

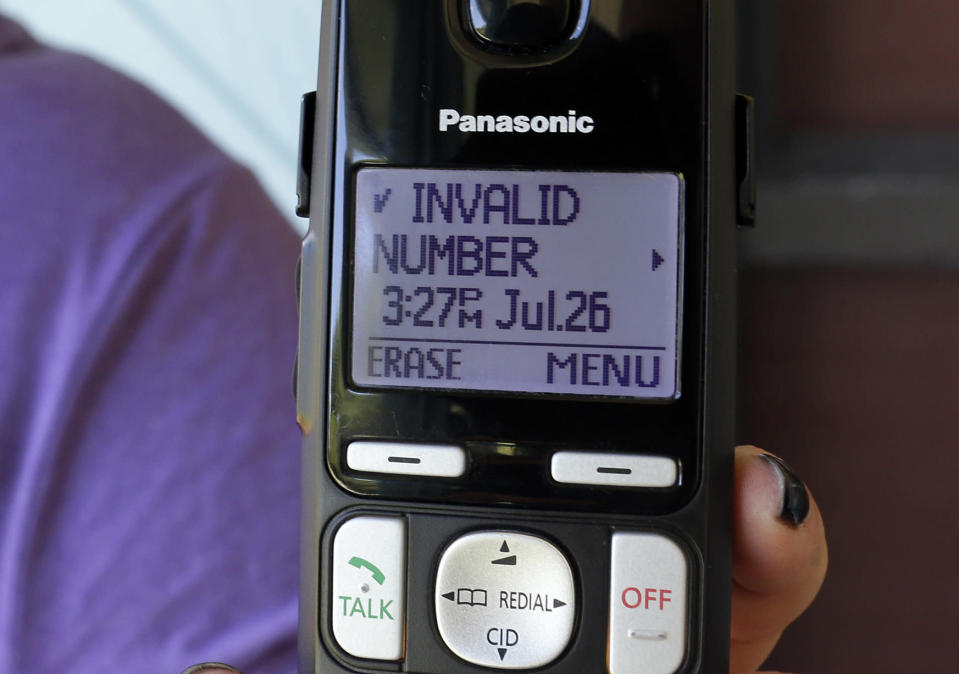

The first type are calls from inbound-only numbers. For example, the IRS never calls out on some of the phone numbers it uses. So any call made with that caller ID can automatically be considered fraudulent. Other kinds that can now be blocked: invalid, ridiculous numbers in weird formats or clearly fake numbers like 1-000-000-0000 or 1234567 can be canceled. The last two kinds of blockable calls: numbers that haven’t been allocated to carriers and numbers carriers haven’t yet assigned.

“If those numbers haven't been allocated, they shouldn't be making phone calls,” says Rupy. So far, tons of these calls and numbers have been blocked by major carriers, preventing at least a portion of harmful IRS scams.

This is not as good as it sounds, an industry insider told Yahoo Finance. Despite the amount of media attention, there really aren’t that many big, large scale scam/spam campaigns for things like the IRS or others, so the impact is small.

Furthermore, number allocation and assigning is bureaucratic and potentially slow, meaning that a number may be thought of as “unassigned” or “unallocated” by one system while being completely legitimate and actually belongs to a teacher in Nebraska. Since many carriers want to avoid these unintended consequences, they’re less willing to block.

The blocking permission also leads to another question: when do you block? Perhaps there is a consensus around scam calls. But annoying, legal calls from politicians or telemarketers? How do you make sure a school closing call isn’t considered an unwanted robocall?

The whack-a-mole situation

In March 2017, T-Mobile became the first major carrier to launch a blocking assault on robocalls with a network-level tool that screened and blocked calls.

“We were the first, and for a long time the only, major wireless provider to deliver free scam protection to all our [non-prepaid] customers with Scam ID and Scam Block,” T-Mobile spokesperson Katie Recken told Yahoo Finance. (AT&T says this is “inaccurate” because it launched AT&T Call Protect in December 2016.)

These products told customers automatically when a call is likely to be spam, and the blocking feature simply allowed a user to block all the suspected calls.

Soon after T-Mobile’s innovation, however, something happened.

There had been plenty of neighborhood spoofing before, with scammers faking caller ID so it looks like they have your area code and possibly also your central office (the second three digits in a phone number).

But after T-Mobile started blocking millions upon millions of spam calls, neighborhood spoofing appeared to evolve into something far more advanced.

“Verizon estimates that for its wireline and wireless networks between March 2017 and August 2017, neighborhood calling patterns increased by approximately eightfold,” the company wrote in a letter to the FCC. (Verizon is the parent company of Yahoo Finance.)

The company told the FCC its hypothesis: bad actors were able to bypass blocking techniques by spoofing the last four digits of the outgoing caller ID number with random numbers. In addition to the neighborhood spoofed area code and central office code, the random numbers made it far more difficult to stop — some numbers are used just once.

Like a mutating virus, spammers evolved to conquer the barriers put in place.

This explosion in neighborhood spoofing aggravated the problem significantly. According to one industry source, Voice-over-IP-protocol (VoIP) has made spoofing so easy that some spoofers use a different number for each call. And with so many randomized numbers flying around similar to real area codes, the chances of hijacking some unsuspecting customer’s number also exploded — that’s what happened to me and so many others.

Because the numbers aren’t actually owned and operated by the scammers, this makes blocking far more difficult. For example, my number has been used to make spam calls, but it would be a disaster for me if Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile and the others decided my number was spam and put it on the blacklist.

One industry insider at a large carrier told Yahoo Finance that fear of unintended consequences for customers prompted extreme caution when it came to blocking, without some form of authentication to beat the spoofing. Doing so, the insider said, could just cause the bad guys to spoof more.

The solution in the works

The playbook for solving the robocall problem – or reducing it to a manageable degree – has been written.

It’s called STIR/SHAKEN.

During the Obama administration, the FCC organized a group of stakeholders called the "Robocall Strike Force.” The solution that the Strike Force promoted was addressing robocalls by tackling spoofing. And to beat spoofing, the caller ID faking, which is not difficult to do, says Rupy, authentication is key.

STIR/SHAKEN is a protocol phone companies are being encouraged to adopt that uses certificates to verify that a call came from a certain phone. Essentially, a carrier “signs” a call that goes out with an encrypted key, and the receiving carrier decrypts it and checks to make sure it’s legit. If the certificate doesn’t match up, the call could be labeled or blocked.

The timeline for STIR/SHAKEN? According to a November letter to the FCC from Verizon, the company expects calls to be "signed" by the STIR/SHAKEN authentication technology in 2019. Parts of Verizon Wireless's platform are already STIR/SHAKEN-ready, the company wrote, and it expects the rest of the wireless system to be ready in the first half of this year.

T-Mobile is also on track, having announced STIR/SHAKEN readiness in November 2018. “We are ready today to peer with others that have adopted the FCC-recommended SHAKEN/STIR standards,” the company wrote the FCC in November.

AT&T’s timeline has it testing the exchange of signed calls with Comcast and two other anonymous carriers in the second quarter of 2019, and then rolling out the system to sign all wireless calls in the third quarter of 2019.

On its face, this sounds like the end. But a close reading of the letters shows the ways cracks could form. Just because one company signs its calls with the proper authentication doesn’t mean that another company will sign their calls properly or bother to check the authentication from carriers that come in.

Other questions emerge, since it’s the service providers themselves which sign calls. When can a provider not sign? What if only some companies cooperate? A call is passed off through many different companies and systems in its journey from one ear to another.

Some companies like AT&T noted these concerns in their letters to the FCC’s Pai.

“It will take enormous commitments on the part of each company for SHAKEN/STIR to achieve its potential and restore consumers’ confidence that they can answer their telephones without being subjected to illegal robocalls,” AT&T wrote in its letter to the FCC. “The timeline necessarily is dependent, in significant part, on factors beyond AT&T’s control, including coordination with other voice service providers.”

“This is where the rubber meets the road,” one insider told Yahoo Finance.

Verizon, in its letter, highlighted another issue – companies signing calls they aren’t supposed to, after the framework is implemented.

“Some unscrupulous voice providers routinely look the other way while originating millions of calls that they know or should know are illegal,”Verizon’s counsel wrote to the FCC. “Voice providers must have meaningful processes in place to void originating illegal robocall traffic or traffic that is unlawfully spoofed.”

Though this golden solution exists in theory, no one knows the impact it will have. Will one bad apple spoil the whole bunch if most companies make a goodwill effort in its spam-fighting but a few small players look the other way and allow spam? It looks like we won’t know until 2020. All we can hope for now is that it will be enough to make a difference.

-

Ethan Wolff-Mann is a writer at Yahoo Finance focusing on consumer issues, personal finance, retail, airlines, and more. Follow him on Twitter @ewolffmann.

A new type of caller ID will give legitimate calls an edge over spam calls