Netflix's Reed Hastings is Yahoo Finance CEO of the Decade

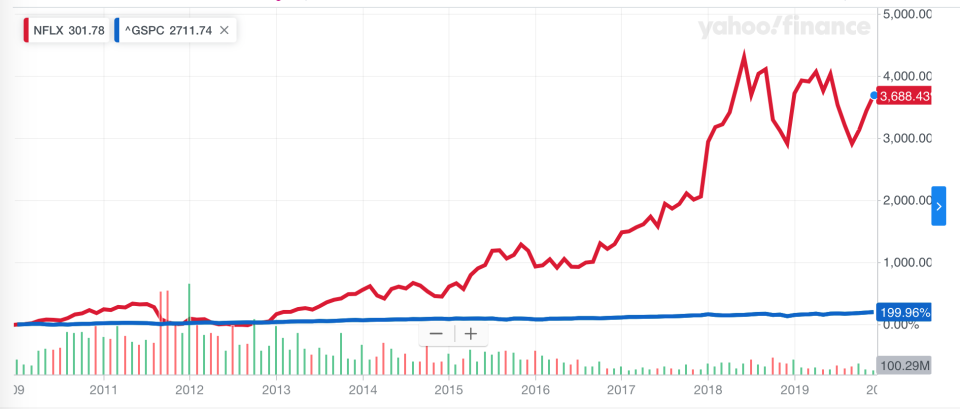

Netflix was an $8 stock in late December 2009. Since then, shares have risen a jaw-dropping 3,700%, making it the No. 1 best-performing stock of the decade—and the rest of the top 10 weren’t even close.

That makes sense: Netflix (NFLX) is arguably the most incredible business reinvention story of the 2010s.

In the first few years of the decade, it pivoted from a DVD-by-mail company to a digital streaming giant; in the latter half of the decade, it pivoted from a home for licensed content to a kingmaker of premium original content and a perennial Oscars contender.

That was all led by cofounder and CEO Reed Hastings. That’s why Hastings is our pick for CEO of the Decade.

Separately, we’ve crowned Netflix’s competitor Disney (DIS) our Company of the Decade. You might ask whether those two accolades contradict each other. We don’t think so. No two companies have more clearly defined the past decade in American pop culture and entertainment than Disney and Netflix.

You could make the case that Netflix should be our Company of the Decade and Bob Iger our CEO of the Decade. But while Iger’s M&A moves have helped Disney grow from a huge entertainment giant into an even huger entertainment giant, Netflix’s story over the last 10 years has truly been one of complete reinvention, steered by Hastings. He has also returned more value to shareholders than any other CEO (Disney stock rose only 400% in the decade).

[See past Yahoo Finance Companies of the Year: Target; Square; Amazon; Nvidia; Facebook; Under Armour; Disney.]

And while Netflix in 2019 has faced more competition than ever before, leading to some subscriber attrition and new concerns about its future, it remains the incumbent giant of the streaming wars thanks to building up a very early lead over all other content-makers.

Read on for more on exactly how Hastings built the most formidable disruptor in Hollywood.

Evolving past DVDs

Reed Hastings and cofounder Marc Randolph started Netflix as a DVD-by-mail subscription in 1997 and brought it public in 2002. (I still remember watching every season of the FX show “Rescue Me” that way.) The company hit 1 million subscribers in 2003.

By 2005, Hastings could see that the eyeballs were heading online, so Netflix began designing a digital strategy. It was planning on a system where users could download movies overnight.

Former Netflix content VP Robert Kyncl, now chief business officer at YouTube, writes in his 2017 book “Streampunks” that the explosion of YouTube prompted Hastings and Netflix CCO Ted Sarandos to rethink that plan. “Witnessing the popularity of YouTube was a revelation,” Kyncl writes. “And it caused us to stop our launch and pivot to a service that would allow consumers to stream movies remotely instead of downloading them. That pivot took two long years, during which we had to renegotiate all our rights and build an entirely new architecture to host and serve content… finally, in 2007, we launched Netflix streaming because we saw the potential that YouTube presented.” (You might choose to take Kyncl’s version of events with a grain of salt, considering he’s now at YouTube.)

At first, Netflix offered streaming as an add-on to the DVD option for an additional fee, but by 2010 Netflix boasted 20 million subscribers and launched streaming as a standalone subscription option. At this point it was competing with Amazon (which had launched video in 2006), Blockbuster (which was launching unlimited DVD rentals for $20 per month to undercut Netflix), and Hulu (launched in 2008). But Hastings is famously laser-focused and has said in interviews that he didn’t take his cues from competitors. (He also happily acknowledges mistakes: in 2011 he announced in a Netflix blog post that the DVD business would be renamed Qwikster, a decision he took back one month later.)

Netflix cofounder Marc Randolph, recalling the launch of Netflix streaming, told Yahoo Finance it was “an almost linear progression of something that’s been in [Netflix’s] DNA since the very beginning… I think it’s kind of informative, actually. If you’re trying to figure out where a company is going, look back to the beginning. It was not about the delivery mechanism, it was not about shipping DVDs, it was not about streaming—it was about helping people find content that they love.”

Netflix streaming has now become so ingrained in television culture that many people may not even remember seeing those red envelopes in physical mailboxes. Believe it or not, Netflix still has 2.7 million subscribers who choose to receive DVDs.

Original content spending boom

Even after Netflix launched a standalone streaming option in 2010, everything on its service was licensed content—shows and movies made by other entertainment companies. Jumping into original content was such an additional reinvention that some have called that, along with the move from DVDs to streaming, a “double pivot.”

“House of Cards” is typically cited as the first Netflix original series, but it was actually “Lilyhammer,” a gangster show starring Steven Van Zandt from “The Sopranos” and co-produced with NRK in Norway, which hit Netflix in 2012 and was touted as the first “exclusive content” on Netflix.

Still, “House of Cards” was certainly the show that kicked off Netflix’s spending boom and made “Netflix Original Series” a household concept. The show cost $60 million per season to produce—chump change compared to the $130 million Netflix reportedly spent on “The Crown,” making it either the most or second-most expensive television show ever.

“House of Cards” and “Orange is the New Black” both premiered in 2013 and helped lure millions more subscribers to Netflix. “The Crown” and “Stranger Things” came in 2016.

Television critics like to talk about the “golden age” of TV, and they’re usually referring to HBO, Showtime, and AMC, to the stretch of high-quality original series that started with “The Sopranos” in 1999 and included “The Wire” (HBO, premiered in 2002), “Dexter” (Showtime, 2006), “Mad Men” (AMC, 2007) and “Breaking Bad” (AMC, 2008).

But Netflix arguably continued the “golden age,” or ushered in a new one. Now people talk about “peak TV,” and when they do, they’re talking about Netflix and other original streaming series. Every platform has its iconic first big original show that gave the platform a foothold in the streaming wars, and Netflix started the trend: “House of Cards” and “Orange is the New Black” for Netflix (nowadays it’s “Stranger Things”); “Transparent” and “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” for Amazon Prime Video; “The Handmaid’s Tale” for Hulu; and now “The Mandalorian” for Disney+.

Netflix spent $15 billion on original content in 2019, and its spending has become the most popular concern for bears to focus on. Netflix’s rising spending, plus subscriber dip in 2019, add up to such a problem that analysts at Needham this month downgraded the stock to a sell and declared that Netflix must add a second, lower-priced tier that has advertisements.

Not a chance, says Bank of America analyst Nat Schindler. “Reed is extremely adamant that that won’t happen,” he says. As for concerns about spending, Schindler says, “Their operating margins are going through the roof very quickly, so they can spend off their real earnings.”

Netflix recently reported it has 158 million global subscribers, and 90% of its growth is coming outside of the U.S. The streaming giant reported $15.7 billion in revenue for 2018 and $1.2 billion in profit, up from $6.7 billion in revenue and $122 million in profit in 2015.

Still, Netflix did have a rocky 2019. The stock rose only 25%, narrowly underperforming the S&P. Schindler, who named Netflix as Bank of America’s top FAANG pick for 2020, says it was “a perfect storm of problems. Largest price increase they’ve done, 18% in one swoop, that does increase churn. But every time we’ve seen price increases in the past, that increased churn lasts for a short period of time, 6-9 months. And at the same time, everybody was talking about Disney+.”

Disney+ and other new competitors

Indeed, 2019 brought more new streaming competition than Netflix has ever faced, from Disney+ and Apple TV+ (both launched in November), and, coming in 2020, NBC’s Peacock and WarnerMedia’s HBO Max.

And those are just the new players. The endless list of over-the-top subscription offerings also has Hulu, Vudu, Fubo, YouTube, CBS All Access, and sports services like ESPN+, DAZN, and FloSports.

Might we soon be approaching “peak streaming,” where consumers start to examine their OTT platter and decide they need to cut some subs?

“I don’t think we hit that time for quite a while,” says Schindler. For starters, 56% of TV viewing still happens on live linear television. It may feel like everyone across America is cutting the cord, but they haven’t yet. Eventually, Schindler says, “That’s going to switch. And people aren’t going to have that old form, they’re going to only have the new form, and they’ll go to where the content is. Right now, and probably for a long time to come, Netflix has the content.”

As for Disney+, which has quickly amassed 24 million subscribers in its first month, Schindler doesn’t buy the narrative of a Disney+ vs. Netflix race. “It’s a great story,” he says, “but it’s just not true. Content is not fungible. If you take a piece of content, that’s not the same as another piece of content. If you want to watch ‘Kimmy Schmidt,’ you’re not turning on HBO, and if you want to watch ‘Game of Thrones,’ you’re not turning on Netflix. ‘The Mandalorian’ might be great, but it’s not ‘Stranger Things.’”

Schindler isn’t making a value judgment there, he’s pointing out something that is obvious but nonetheless gets forgotten in headlines that pit every streaming service against the other: if you want to watch a certain show, you have to subscribe to the one platform that has that show. For now, that means every service that has a marquee series people think is must-watch can keep subscribers on the strength of that series. The streaming wars are not zero-sum—yet.

Content creators spent a staggering $650 billion on original content in the past five years. As the spending extravaganza continues, Netflix is poised to thrive, thanks to the foundation Hastings built.

“He’s a visionary, and he’s been very narrow and focused for a very long time,” Schindler says. “But he’s also been great at hiring. He pulled in people who got him to do things that even he didn’t want to do at the time, mostly original content. And I think the original content move, from basically two shows a year to 100, in very short order, that changed the game.”

One stunning example of Netflix’s evolution into the top creator of high-quality TV and film: this month it scored 34 Golden Globe nominations. The networks ABC, CBS, and NBC got zero.

Randolph, describing the culture Hastings has established at Netflix, uses the same word so many others do: focus. “The only thing they do is what they’re doing. Disney of course has a range of business, [so does] Apple. I think the thing [they’ve] got to worry about is when Netflix either launches a theme park or brings out a telephone.”

—

Daniel Roberts is an editor-at-large at Yahoo Finance and closely covers Netflix, Disney, and the streaming wars. Follow him on Twitter at @readDanwrite.

Read more:

Disney+, Apple TV+ and Netflix can coexist—for now

Discovery CEO predicts ‘carnage’ in the streaming wars

When will America hit peak streaming?

Can we trust Netflix’s viewership numbers?

Disney+ success is crucial to Disney’s future, Bob Iger has made clear

Disney says streaming is now its ‘number one priority’

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance