Number of female managers on Wall Street is still low but improving

When Katrin Dambrot began the Financial Women’s Association (FWA) of New York’s Back2Business returnship program in 2016, she expected participants to consist largely of new mothers and junior employees with a few years’ experience that had stepped away to start families. But what she found was women with significant experience, some at the managing director level, who were out of work. And they all shared one persistent worry.

“Women who had left the workplace were extremely reticent to even apply for anything,” Dambrot told Yahoo Finance. “They felt they didn’t have a place at the table anymore. They felt that if they had been away for a couple years that nobody would want them.”

The Back2Business program seeks out women who have been out of the financial services industry and places them in trial positions with partner companies such as BMO Capital Markets, Deloitte, New York Life and PGIM in paid assignments that last from 90 days to a year, with both sides hoping it leads to a permanent position.

One of the most important parts of the program, Dambrot added, is that it provides participants training workshops and mentors, which many women say has been acutely absent in financial industry for some time.

The industry stats for women are dismal

In asset management, women today represent 47% of the total workforce, but only 10% of fund managers. Of all mutual funds managed in the United States, just 2% are run by a woman or a team of women. In contrast, 76% of funds are run exclusively by men, according to Morningstar data.

Those numbers lag many other professional fields. Women make up 37% of medical doctors, 20% of law-firm partners, 24% of federal judges and 19% of partners in U.S. accounting firms.

Data from Morningstar analyzed by Yahoo Finance found that over the last 15 years, the number of U.S. debt and equity funds managed by a team that includes a woman has stayed exactly the same.

Why the discrepancy? Some chalk it up to outright gender discrimination, while others opine that’s just the way things are. Conversations with dozens of women in senior positions on Wall Street, as well as researchers, hiring managers and recruiters, suggest there isn’t a simple answer.

“If you’re looking for someone with a 15-year track record, there aren’t a lot of women around,” said Diane Garnick, a board member of the CFA Research Foundation and managing director and chief income strategist at TIAA.

One major reason for this is that women have historically not gotten the chance to build a long-term track record. Companies typically want to hire fund managers with a minimum of five years of experience. If managers leave the industry for more than a few months, they can no longer claim the record that they’ve built and essentially have to start from scratch. This can leave women feeling they have to choose between having a family or caring for an ailing older relative, responsibilities that disproportionately fall to women, and succeeding in their careers.

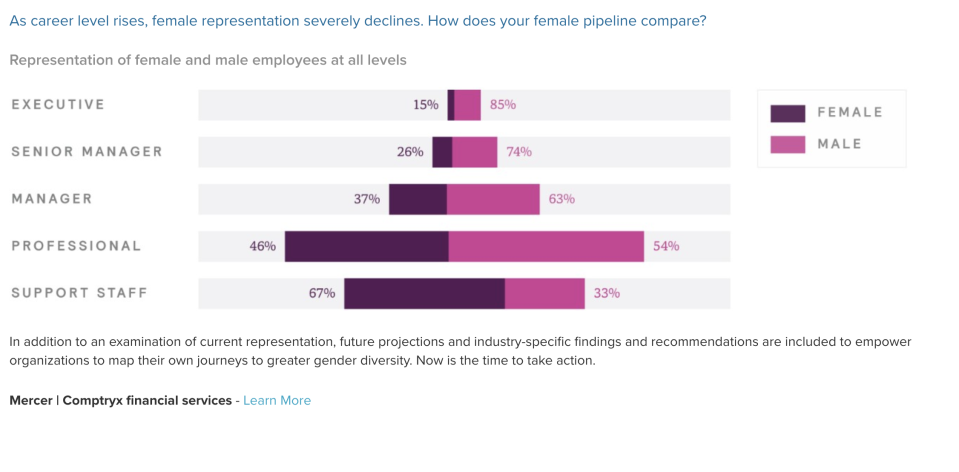

And even when they manage to avoid a lapse in their records, academic research shows women are passed over for promotions, despite having strong performance. A survey from business consulting firm Mercer found that women were weren’t promoted as often because of “overly narrow criteria for advancement, outdated leadership models, inflexible working practices and bias in talent management.”

“You can’t hire what doesn’t exist”

There is general consensus that Wall Street firms aren’t overtly denying women opportunities, but the divide nevertheless persists.

“Obviously you can’t hire what doesn’t exist,” said Meredith Jones, an alternative investment consultant and author of “Women of The Street: Why Female Money Managers Generate Higher Returns (And How You Can Too),” in reference to the low number of women in high positions in asset management.

One major issue is bias, both conscious and unconsious

“When people are looking to hire traders or portfolio managers they tend to hire people that look like the last person that was successful,” she told Yahoo Finance. “So you’re likely to look for a white male because that’s the last person who was successful in that position.”

Jones points to what she calls her “Jim/Bob ratio.” In her survey of hedge funds she found 11 fund managers named John, James, William or Robert for every one female fund manager.

Even when they do get the opportunity to lead teams or take top positions, many women find they are hamstrung by the perception of investors as well. One fund manager, who asked to remain anonymous, said that in seeking investors she once met a venture capitalist whom, after hearing her funding proposal, told her, “I’m not sure whether to give you money or f— you.”

Another fund manager, who also requested anonymity, said that to many firms’ clients, an older man is seen as wise and regal, while an older woman is seen as forgetful.

“Older women take on this perceived grandmotherly role whereas men are seen as more seasoned,” she said.

The data suggests gender bias in the industry is real

The dynamic of bias, whether conscious or unconscious, is evident in the data.

A recent CityWire investigation found that women typically run smaller funds than men, $315 million on average compared to $533 million for men.

Similarly, a 2015 study that tracked U.S. equity mutual funds from 1992 to 2009 found female-managed funds experience significantly lower money inflows than those managed by men and that the growth rates of female-managed funds were about one third lower than those of male-managed funds. Even when funds managed by women performed well, the fund generated smaller inflows.

Both studies found that men and women either have similar performance or that women tend to outperform men on a total return basis.

“When you ask the average person what’s their image of a really successful fund manager, they don’t conjure up a woman and least of all a black woman,” said Tina Byles Williams, chief executive and chief investment officer of asset manager FIS Group. “If she’s really good, really successful, she’ll gather assets, but it’s impossible for someone to always be good. That’s Bernie Madoff territory.”

No straight path to the top

A 2015 study by Alexandra Niessen-Ruenzi and Stefan Ruenzi of the University of Mannheim also found that when female fund managers have down years, investors pull their money out of the funds more quickly than from comparable funds managed by men.

“When you’re on the downside of your performance cycle, that’s where you need that benefit of the doubt,” Byles Williams said. “And that’s where it becomes most problematic.”

Analysis from a Harvard Business Review study shows that at every level, “Men are promoted at materially higher rates than women,” and that “Women are far more likely than men to leave the industry or to reduce their level of ambition just at the point in their careers when they need to make the effort to push on to the top.”

The idea that women don’t have a straight path to the top of investment management has caused them to leave the industry and also scared many women away from entering it. In a Pricewaterhouse Coopers poll, one in five female respondents said they did not want to work in financial services as a result of the image of the industry as male dominated. Further, 60% say financial services firms are not doing enough to encourage diversity.

But things are slowly changing

However, firms do appear to have recognized the need to bring more women into their ranks. In addition to FWA’s Back2Business, a number of companies have begun similar programs for women who have stepped away from the workforce. Companies like JPMorgan, Fidelity and UBS have launched their own re-entry programs in search of female talent.

“The beauty of the program is you end up with women incredibly talented who otherwise wouldn’t have gotten a foot in the door and are grateful for someone to have given them opportunity to get back into the workforce,” said Dana Ritzcovan, head of human resources for the Americas at UBS.

Ritzcovan says UBS has launched a number of initiatives, including voluntary unconscious bias training, mentoring groups called “coaching circles,” and a phase-back program in which women who had previously been out of the industry can work two or three days a week and still earn full-time pay. CEO Sergio P. Ermotti has set the goal of having 30% of its management roles helmed by women.

These programs are not simply altruistic ventures, though. While firms like BMO, New York Life and Deloitte are glad to add experienced women and diversify their workforce, they’re also doing it at a discount. One woman who was recently chosen from a re-entry program by a major investment bank told Yahoo Finance that she’ll be making about 50% of the salary she earned as a manager in the 1990s. That number doesn’t include her bonus, which can make up the lion’s share of Wall Street bankers’ total pay.

Still, there’s an argument to be made that things could be much worse. At the very least, things are moving in the right direction.

Some institutions are starting at the source, such as Girls Who Invest, which looks to increase the pipeline of young women into the financial industry by offering educational programming, providing internships and partnering with financial firms to get participants jobs.

Developments like these have spurred some hope that Wall Street may become a more welcoming place for women.

“Most firms recognize the importance of diversity, in particular diversity of thought, and women bring a different perspective to the table than men,” said TIAA’s Garnick. “That’s the big difference between now and 20 years ago. Then it was all about getting women into organizations; today it’s all about giving diverse people a voice at the table to create alpha.”

And then numbers reflect improvement. Pension and investment funds and endowments have been steadily increasing allocation to so-called emerging managers, or funds overseen by women or minorities. According to the latest report from accounting firm KPMG, mandates and programs for emerging managers rose to 10% in 2016 from just 2% in its first survey in 2013.

—

Dion Rabouin is a markets reporter for Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter: @DionRabouin.

Follow Yahoo Finance on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance