Experts: Gillibrand’s opioid legislation is not 'the right way to do it'

Democratic presidential candidate Senator Kirsten Gillibrand’s (D-NY) announced bipartisan legislation with Sen. Cory Gardner (R-CO) on opioids has been met with backlash on several levels.

Gillibrand announced her plan on Twitter, writing: “If we want to end the opioid epidemic, we must work to address the root causes of abuse. That’s why @SenCoryGardner and I introduced legislation to limit opioid prescriptions for acute pain to 7 days. Because no one needs a month’s supply for a wisdom tooth extraction.”

Gillibrand’s tweet received more than 17,000 responses, with many of them negative and critical of her plan.

Journalist Abraham Gutman, who covers legal and illegal drugs at Philadelphia Inquirer, responded with a lengthy Twitter thread critiquing the proposed legislation.

Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad. Bad bad. Bad.

This is bad policy that will *NOT* save lives and will hurt chronic pain patients — including driving people to commit suicide. We’ve seen this happen before. https://t.co/DDpCHWZdWU— Abraham Gutman (@abgutman) March 19, 2019

Following the negative social media feedback, Gillibrand published a post on Medium titled “I hear you—and I want to get my bill on opioids right.” In the post, she wrote that she “fundamentally believes that health care should be between doctors and patients” and that the intention of her bill is not to get in the way of that, but rather ensure that doctors prescribe opioids with a higher level of scrutiny.

Gillibrand’s office declined to comment. Gardner’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

‘I don’t think this is the right way to do it’

One expert critic of the proposed legislation is Dr. Ryan Marino, an emergency medical physician and medical toxicologist at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

While Marino is happy that politicians want to get involved and help, “I don’t think this is the right way to do it,” he told Yahoo Finance.

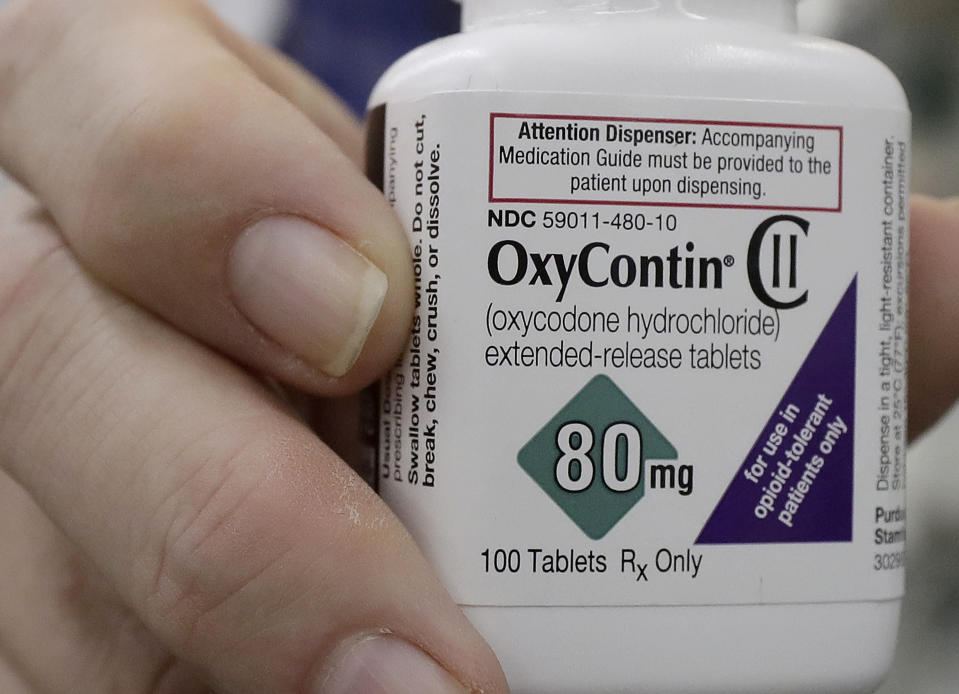

The announcement states that the bill “would create a seven-day prescription limit for opioids so that no more than a seven-day supply may be prescribed to a patient at one time for acute pain, such as a wisdom tooth removal or a broken bone.”

But “I haven’t seen how they’re defining acute pain or acute issues,” Marino said, “which is going to be a big problem, because that definition itself is my biggest issue with this proposed legislation.”

Gillibrand’s Medium post stressed that her bill would only apply to initial prescriptions, so those in need of refills for acute pain would receive them at the discretion of their doctor. However, Marino raised concerns about that aspect.

“This bill would make it so that [patients with severe pain] have to go back and see a doctor and get a new prescription, which would involve paying for another appointment, transportation there, and another prescription,” Marino said. “It’s an excessive burden to both patients and physicians. A lot of time, if a good surgeon knows their patient can call them on day eight, they could have just refilled it. That’s no longer going to be the case.”

‘There are lots and lots of causes to the opioid crisis’

Another issue with Gillibrand’s approach is her claim that overprescription is one of the root causes of opioid abuse.

“There are lots and lots of causes to the opioid crisis,” Bradley Stein, director of the RAND Opioid Policy Center, told Yahoo Finance. “Certainly prescribing of opioid analgesics where they may not have needed to be is one of the contributors, but to say that’s the primary contributor, I think we know there are many others.”

Brett Giroir, assistant secretary for health and senior adviser for opioid policy at the Department of Health and Human Services, previously told Yahoo Finance that many factors play a role in how this opioid crisis came to be, including “the overprescription and inappropriate prescription” of opioid painkillers to patients, the “availability and importation” of low-price, high-potency drugs, and “the role of state and society” in allowing the opioid crisis to build.

So, essentially, overprescription is just one cog in the system of this epidemic.

According to the CDC, the overall national opioid prescribing rate declined from 2012 to 2017, reaching its lowest level in 10 years in 2017. However, that year, “in 16% of U.S. counties, enough opioid prescriptions were dispensed for every person to have one.”

Stein noted that “as a nation, we’re probably prescribing more opioid analgesics than we should be or need to be. The idea we want to reduce the number of opioid analgesics being prescribed, I applaud that.”

However, he added, “we need to approach doing that in a way that recognizes there’s an entire range of approaches that are clinically appropriate here, ranging from trying to encourage physicians and prescribers not to prescribe opioids at all when we have better alternatives, to prescribing as few days as possible, if that’s 3 days or 17 days or 14 days.”

Gillibrand’s proposal states that the 7-day limit would exempt those with chronic pain, cancer patients, those in hospice or end-of-life care, and those being treated for pain as part of palliative care. She noted that this is modeled after existing laws in 15 states.

However, Marino said that these laws in place “haven’t demonstrated any efficacy” in curbing addiction.

“We don’t know that seven is necessarily any sort of magic number, whereas six days or eight days might be better or worse,” he said. “It’s very arbitrary to begin with.”

‘Our country has a tremendous way to go ...’

There are also potential financial ramifications that come with a bill like this.

The main financial burden will likely be on patients, Marino said. As someone who works in an emergency department, he said that he’s seen patients who need refills on medications and going to the emergency room is their only option.

“I imagine that in this case, that would increase those types of visits,” Marino said. “And so that means another copay, long waits, and adding to the ED overcrowding and issues that we have.”

In 2017, nearly 49,000 people died from opioid-related overdoses, with synthetic opioid fentanyl being the biggest driver.

Right now, Stein said, “so many of our deaths are being driven by individuals. Maybe they’re overdosing on heroin or fentanyl. So, a response to the crisis needs to consider a full range of options that may include ways to improve the prescribing of opioid analgesics in this country. But, also, it needs to address the tremendous need we have to expand access to effective treatment in this country. … Our country has a tremendous way to go to make sure people who want treatment can get access to their treatment.”

In October 2018, President Trump signed a new opioid law that was described as “historic in its breadth.” It was aimed to target overprescription and drug trafficking.

“We need to consider a range of approaches to harm reduction,” Stein said. “This idea that there’s a single root cause may not sufficiently recognize the complexity of the crisis, and the range of policy responses we’re really going to need to effectively address them.”

Adriana is an associate editor for Yahoo Finance. Follow her on Twitter @adrianambells.

READ MORE:

'It didn't happen overnight': How the U.S. opioid crisis got so bad

FDA opioids adviser: 'One thing is clear' about the ongoing crisis

'It didn't happen overnight': How the U.S. opioid crisis got so bad

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.