PRESENTING: The chart that defined 2016

The biggest story in the world this year — markets, economics, politics, anything — was the US presidential election win by Donald Trump.

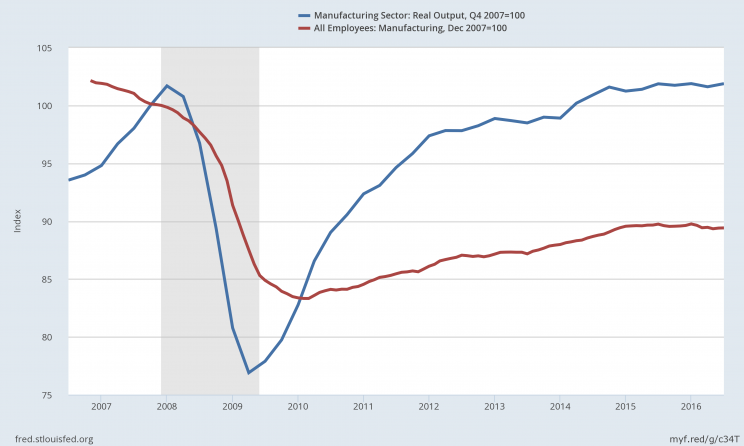

And no single chart told the story of Trump’s election better than the following, which revealed the inconvenient truth about US manufacturing employment and US manufacturing output.

What we see in this chart is the red line showing US manufacturing employment levels about 10% below where they were a decade ago. The blue line shows manufacturing output, which in contrast has fully recovered from the recession and then some.

In short, we find that US manufacturing workers are declining in total numbers while the ones that remain are more productive as a group — largely due to increased automation.

During his campaign, Trump made a point of promising to bring these kinds of jobs back to the US. And on the back of this kind of populist economic rhetoric, Trump pulled the upset to take the White House, forging his path to victory by winning states like Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Michigan, which all once served as manufacturing powerhouses.

But our chart of the year shows that the sector has moved on, moved forward, gotten more out of less. And that is why these jobs are never coming back.

Harry Holzer, a former chief economist for the Department of Labor who now teaches at Georgetown University, told Yahoo Finance’s Rick Newman in October, “Trump is misleading people who really think he’s going to bring back good jobs. That’s a pipe dream. The robots have eliminated a lot of them. Nobody’s bringing those jobs back unless they come back at really low wages.”

Wall Street analysts agree.

“A recent wave of election results in developed markets is being interpreted as suggesting frustration among middle and lower income voters with both the Establishment and their economic lot,” analysts at research firm Bernstein wrote in a recent note to clients.

“One means of tapping into that frustration has been for politicians to promise a return of good, well-paying manufacturing jobs to developed markets (well, one developed market in particular). However, thanks to factory automation, that outcome is barely available in Shanghai and Shenzhen, let alone Shreveport [Louisiana] and Scranton [Pennsylvania].” (Emphasis added.)

Because what the automation, or augmentation, or robotization of the workforce has done is make those who remain more effective at their jobs. This is the reality Trump fights when he cuts a tax deal with Carrier to keep 800 jobs in Indiana. And this is the reality Trump fights when he threatens a 35% tariff on goods produced by US companies that move production overseas and import these same goods back into the US.

On Monday, United Technologies CEO Greg Hayes let slip that despite Trump’s deal to keep some of Carrier’s jobs in Indiana (United Technologies owns Carrier) there will, in the end, be fewer jobs.

“We’re going to make a $16 million investment in that factory in Indianapolis to automate to drive the cost down so that we can continue to be competitive,” Hayes told CNBC’s Jim Cramer, referencing the Carrier plant’s plan to remain open as part of Trump’s deal with the company.

Hayes added, “Now is it as cheap as moving to Mexico with lower cost of labor? No. But we will make that plant competitive just because we’ll make the capital investments there… But what that ultimately means is there will be fewer jobs.”

In its note, Bernstein echoed Hayes’ commentary, writing that, “in a world of low-cost and adaptable robots, even the role of the humble trade barrier is up-ended. It is still possible to force the relocation of production through the introduction of tariffs and quotas. However, if the point of the exercise is to restore well-paying, middle class jobs in manufacturing in the process, the result is going to disappoint.

“Any such effort today is likely to result in greater and greater degrees of automation. The activity may come ‘home,’ but there are simply no jobs to steal. Mandating a physical task be carried out in a high-cost labor market in 2017 is simply going to increase the chances the task is automated.” (Emphasis added.)

And so while Hayes admitting that Trump’s recent short-term political win is just that, he’s simply relaying what our chart of the year says about the present, and future, of the manufacturing industry.

And no politician is about to change that story.

—

Myles Udland is a writer at Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter @MylesUdland