Primary care doctor: 'We should all be very worried' about plunging patient visits amid pandemic

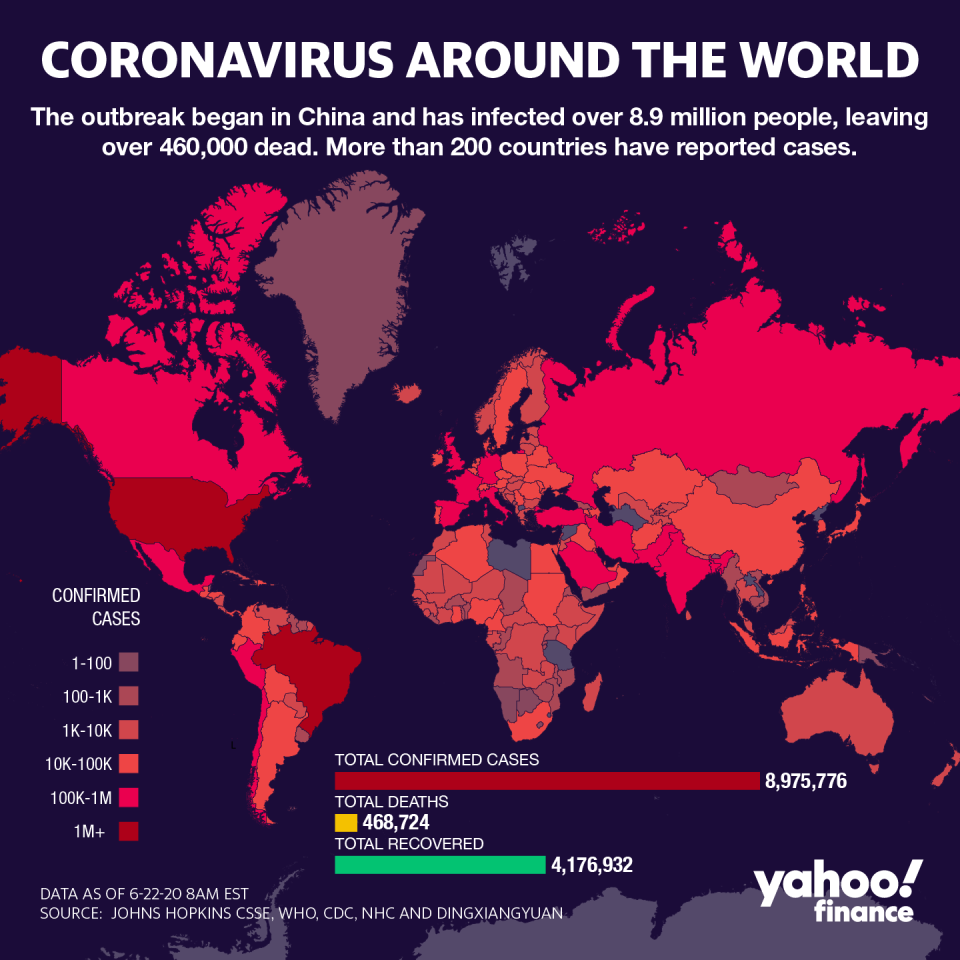

The economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic has affected nearly every U.S. industry.

And health care, including primary care practices, took a serious hit. If it’s not addressed soon, according to doctors and experts, there could be what he called a “second hidden pandemic” to worry about: untreated chronic conditions.

“We know primary care is very important for a very good reason, and the reason is because if you don’t do prevention, you will pay the price in complications and heart attacks and kidney failures and strokes,” Dr. Farzad Mostashari, Aledad CEO and co-founder, said recently during a teleconference call with The Commonwealth Fund. “We’ve seen a dramatic decline in primary care services … but we should all be very worried about the untreated chronic diseases.”

A recent survey by the Primary Care Collaborative, conducted June 5-8, found that 46% of patients have been in contact with their primary care practice at least once over the last two months.

But the same survey found that nearly 65% of clinicians are reporting some level of strain in delivering care to their patients. These strains include lack of PPE (48%), reduction in staff (37%), reductions in patient visits (78%), and rejected telehealth claims (18%). Furthermore, 63% of clinicians say their stress level is an all-time high. These numbers have only slightly improved from a previous survey conducted at the end of March.

‘So much that we have to dig ourselves out of’

When patients can’t see their doctors regularly, things can fall through the cracks.

“Lord knows so many of them need their chronic care maintenance visits and these children need their immunizations and developmental visits and such,” Dr. Gary LeRoy, an Ohio-based family physician and president of the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), told Yahoo Finance. “There’s so much that we have to dig ourselves out of as far as our patient visits and the patient services that are needed.”

This can exacerbate chronic illnesses, which were already a growing issue in the U.S. before the coronavirus pandemic came along. A 2017 RAND study found that 6 in 10 of the roughly 252 million adults in the U.S. have a chronic illness and 4 in 10 have two or more. The Partnership to Fight Chronic Disease estimates that more than 30 million Americans suffer from three or more chronic illnesses.

The treatment of chronic illnesses “is a cost to the health system,” David Hoffman, an associate professor of ethics and health policy at Maria College, previously told Yahoo Finance. “And as a result, everyone’s health insurance is more expensive. It’s more expensive to operate health care institutions because of the demand.”

According to the CDC, 90% of the nation’s $3.5 trillion in health care expenditures were for people with chronic or mental conditions.

“The interesting thing is, when patients can’t and/or don’t want to come into the office, and then you’ve got a lot of staff sitting around saying, ‘What can we do? We’re slow. We’re not seeing patients,’ the pivot for us there is to then proactively outreach to patients,” Dr. Ryan Knopp, a family physician at Stone Creek Family Physicians in Manhattan, Kansas, told Yahoo Finance.

In other words, Knopp said, “calling our highest risk and vulnerable patients for COVID and people that had gaps in their health care, engaging our staff to outreach to them to educate about the pandemic, give guidance, help them understand how our office was functioning, answer any questions, address health care needs, sometimes that even turns into a televisit.”

Dr. Jacqueline Fincher, a Georgia-based physician and president of the American College of Physicians, explained how not being able to check in with your regular doctor can lead to major problems.

“Our local surgeon in our small town told me that in those three weeks of March after things had been declared, he saw two ruptured appendixes,” she told Yahoo Finance. “He hadn’t seen a ruptured appendix in a couple of years, but he had two of them in three to four weeks because people were afraid to go to the emergency room.”

‘Three-fourths of my practice went out the door’

When the coronavirus first started making its way throughout the U.S., governors called for a halt to non-emergency urgent visits. And although many of the practices shifted to telehealth, there were still noticeable changes.

“Three-fourths of my practice went out the door, or just didn’t come in the door because of that mandate,” LeRoy said. “Any business like restaurant services, if you lose three-fourths of your customers, you can only survive so long with a full staff there and one-fourth of your revenue, your customers, coming in the door. Many of us, because of not wanting to lay off or furlough our staff, marched forward trying to have our staff do things and provide services remotely for our patients without having to lay them off.”

Many of LeRoy’s patients found ways to pivot to telemedicine, even though they weren’t initially getting reimbursed for all of it by insurance companies and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

“There was a wide gap between me picking up the phone and calling my patients or our staff calling our patients and providing refills and information to our patients by telephone and realizing that we would not be paid for that,” LeRoy said. “We’ve been doing that for years with our patients.”

And telehealth doesn’t work for everyone: Dr. Jacqueline Fincher said it’s been a “huge issue” for some of her patients.

“I’ve been in practice for 32 years now,” Fincher said. “My practice has grown old with me, so I have a lot of patients who are over 65, have limited understanding or most don’t have a computer. Some of them have a smartphone, but I tell you still, flip phones are still very common around my area. You can’t do telehealth with audio and video if you don’t have a smartphone or computer.”

And there is still a need for in-person visits if a patient needs a physical exam, especially if they are experiencing newer problems.

“That helps you make that differential diagnosis of, is this coming from the GI tract or is this really coming from the heart or whatever?” Fincher said.

A rollercoaster ride

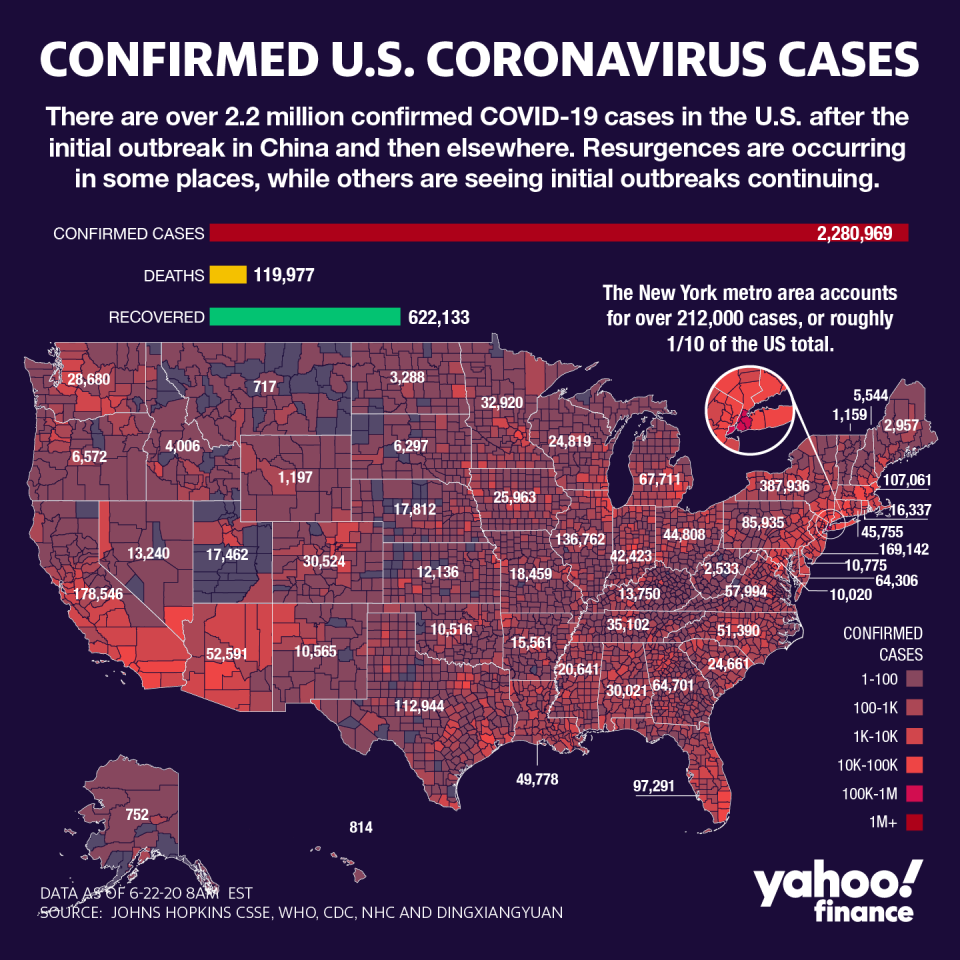

Although states are now in different phases of re-opening, the number of coronavirus cases is only declining in some.

In Arizona, Texas, and Florida — three states that re-opened their economies earlier than most — coronavirus case counts are at the highest levels since April. And if some states are forced to shut down again, that could mean primary care practices take another hit.

“We are going to be on a long rollercoaster ride here — as a clinic, as health care providers, as a country, as a society,” Knopp said. “Needless to say, it’s hard to predict what the future of this pandemic is going to be, but I think all of us understand that it’s going to be a rollercoaster ride.”

Adriana is a reporter and editor covering politics and health care policy for Yahoo Finance. Follow her on Twitter @adrianambells.

READ MORE:

Coronavirus spread is like 'lighting a campfire,' doctor explains

Hospitals itch to ramp up elective surgery amid coronavirus profit crunch

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.