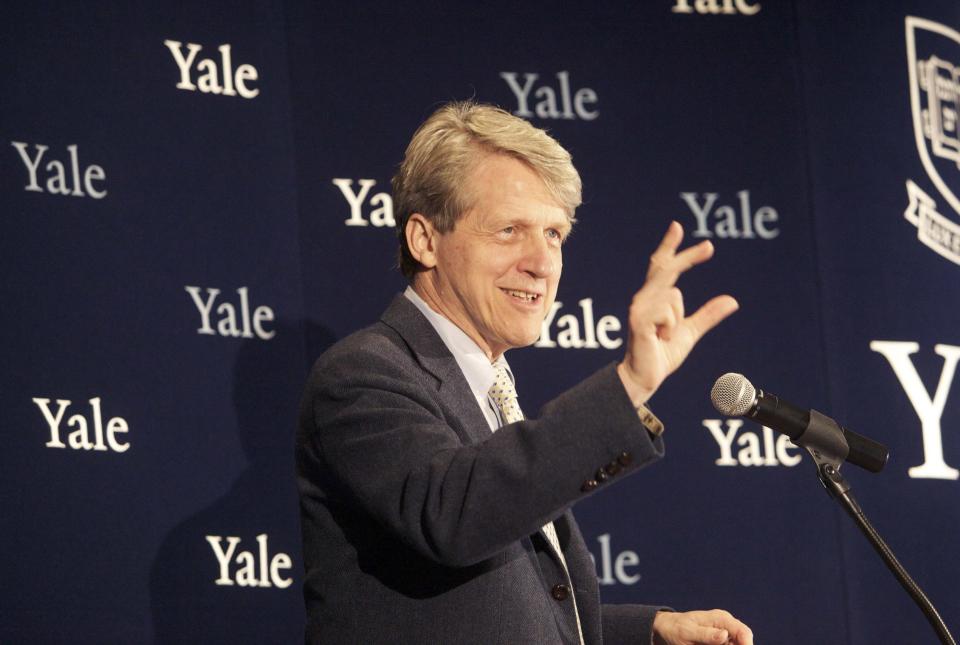

Robert Shiller warns against dumping stocks because of the high 'CAPE' ratio

One of the most closely-watched measures of stock market value appears to be predicting imminent trouble. However, it may be a huge money-losing mistake to actually dump stocks based on its signal.

This measure is the cyclically-adjusted price-earnings (CAPE) ratio, which was made popular by Nobel prize-winning economist Robert Shiller. CAPE is calculated by taking the price of the S&P 500 (^GSPC) and dividing it by the average of ten years worth of earnings. When CAPE is above its long-term average, the stock market is thought to be expensive.

And when CAPE is nearing historic highs, some would say the stock market is on the brink of a crash. It’s a fair concern as other historic peaks occurred in 1929 and 2000, just prior to some of history’s most devastating stock market sell-offs.

Currently, CAPE is hovering near 29x, which is substantially above its long-term average of about 15x. See the chart below, which comes from Shiller.

“[T]he last time that the cyclically-adjusted price/earnings ratio (CAPE) of the US stock market was this stretched, which was around a decade ago, it subsequently plunged,” Capital Economics’ Oliver Jones and John Higgins wrote in a recent note to clients.

Shiller wrote extensively about CAPE in his 2000 classic “Irrational Exuberance,” which marked the peak of the dotcom bubble and solidified Shiller’s place in market history.

But Shiller himself is the first person to tell you to be wary of what CAPE may be signaling.

“Long-term investors shouldn’t be alarmed”

“There is no clear message from all of this,” Shiller wrote in the New York Times in a lengthy piece warning about CAPE’s elevated level. “Long-term investors shouldn’t be alarmed and shouldn’t avoid stocks altogether.”

To be clear, Shiller’s Times piece is about the many signs of an overheated market he sees. However, he has always gone out of his way to clarify that CAPE is only decent at predicting long-term returns, not short-term swings. (CAPE is bad at predicting 12-month returns, and it’s bad a predicting 3-year returns.)

“The CAPE ratio has successfully explained about a third of the variation in real 10-year stock market returns in United States history since 1881,” he said. “The current level of CAPE suggests a dim outlook for the American stock market over the next 10 years or so, but it does not tell us for sure nor does it say when to expect a decline. As I said, CAPE is useful, but it does not provide a clear guide to the future.”

Issues with CAPE

Most would not dare challenge the legitimacy of CAPE, given its track record. But there have been a handful of strategists willing to take a shot.

Jefferies’s Sean Darby has been a long-time skeptic of CAPE’s market-forecasting power.

“While we are not attempting to justify the high valuations of the S&P 500, there are some inherent limitations to solely using the CAPE ratio as an investment tool,” Darby wrote in a March 23 note to clients. Here are four concerns he identified (verbatim):

“Firstly, the S&P is a market cap weighted index and profits will likely be skewed unequally relative to the value of the company.

“Secondly, all models are ‘mean reverting’. Valuations can remain high for long periods of time but stocks can continue to rise.

“Thirdly, the current ten-year profits moving average included a significant compression of profits in 2008-09. Statistically, this is an outlier.

“Lastly, the S&P 500 is itself an index that sees substantial changes to its constituents.”

Darby’s first and fourth points speak to the many issues of using the S&P 500 for anything.

His third point is particularly interesting as we approach the 10th anniversary of the financial crisis. This period from 2007 to 2009 included a time when earnings collapsed, inflating CAPE. Assuming stocks and earnings go sideways for the next two or three years, CAPE would tumble as the equation works out crisis-era depressed earnings.

You never know what’ll actually happen next

“We don’t know where the market will go this month or this year,” Shiller said in his Times piece. “It could well rise a lot.”

This sort of echoes Darby’s second point, in which he notes, “Valuations can remain high for long periods of time but stocks can continue to rise.”

It all speaks to the unpredictability of stock prices, even when the market appears richly valued and the bull appears to be getting old. It’s why it can be frustrating and painful to attempt to predict market peaks.

Having said all that, Shiller is nevertheless concerned about the state of the stock market.

“[I]mportant measurements — some of which I developed — tell us that the market is quite expensive and that investor optimism is tinged with plenty of worry,” he said. “None of this tells us where the market is going tomorrow, but it suggests that some caution is advisable, and that returns over the next decade or so are likely to be constrained.”

Read Shiller’s whole piece at NYTimes.com.

–

Sam Ro is managing editor at Yahoo Finance.

Read more: