A radical, yet simple solution to solve Facebook's problems

…their business was born in a balloon going up, and spent all its early years in the sky." They had seen nothing but the extreme of fortune. One hundred per cent per annum on an investment was in their judgment only a fair profit.

—Ida Tarbell, "The History of the Standard Oil Company" 1904

Facebook’s problems are coming so fast and furious these days that the company’s biggest challenge is simply keeping track of it all.

Between high-profile mega hacks, negligent sharing of data, and lawsuits, never mind investigations by governments all over the world, Facebook’s top executives are expending much of their time trying to stop the bleeding—many would say ineffectually—at the expense of running the business.

Memo to Sheryl and Zuck: There’s a message in that disequilibrium.

At this point it’s probably too much to ask those two—the company founder, cum CEO, cum controlling shareholder and his handpicked, right-hand person—to figure out how to fix Facebook. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg and COO Sheryl Sandberg are too close to it and have too much faith in the righteousness of what they consider not merely a company, but a cause.* (Dangerous thinking that.)

Both Sandberg and Zuckerberg recently posted longish similar year-end messages that both displayed equal measures of earnestness and cluelessness. The posts engendered over 15,000 comments combined, many of them negative.

It’s clear to many Facebook watchers—academics, researchers at think tanks and regulators—that the company is incapable of self-oversight. And to be fair, what company of this scale is? There are reasons why Coke, Walmart, and Comcast, etc. are regulated. Though some might argue they are overly regulated, who would suggest these giants be allowed to operate as unfettered as Facebook does today?

The power of the ‘network effect’

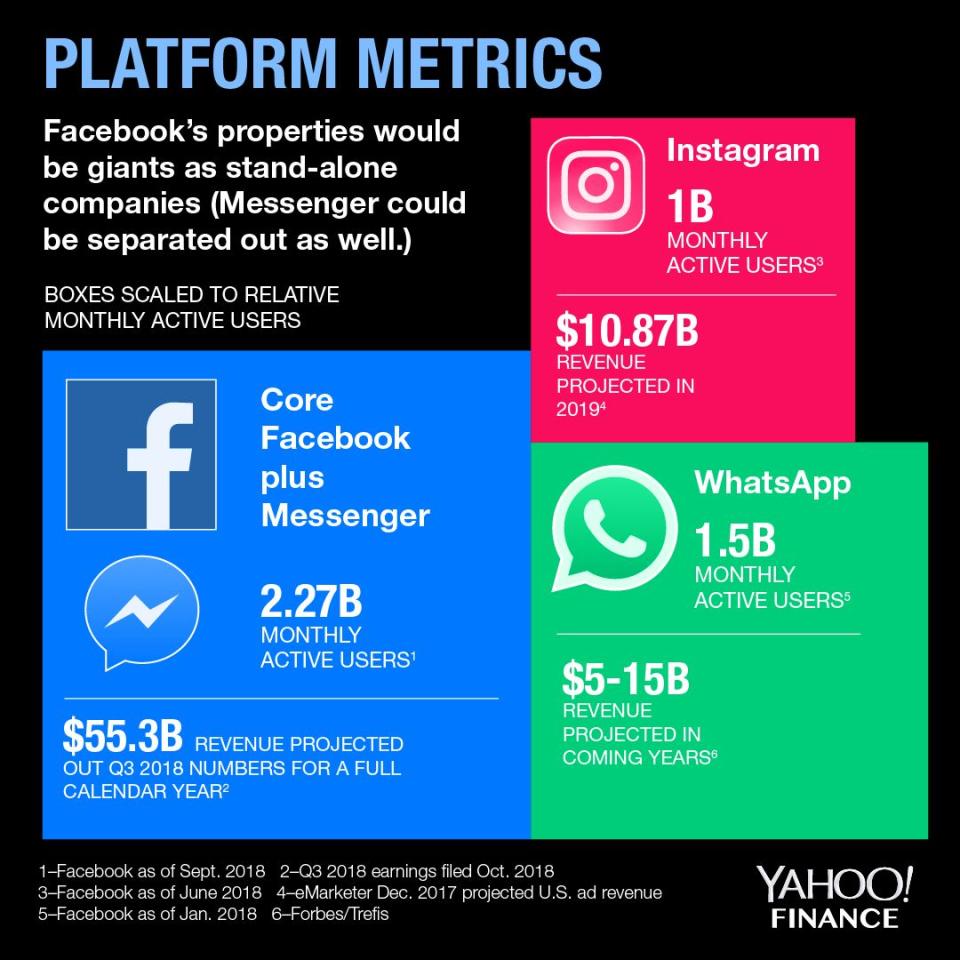

As for Facebook, never in the history of the planet has a company grown so big, so fast in such a new business as Facebook. In October, Facebook said that every day more than 2 billion people use at least one of its “family” of services—which includes photo-sharing site Instagram, messaging app WhatsApp, Facebook itself, and Facebook Messenger.

In addition to those services, Facebook also owns virtual-reality pioneer Oculus, which it bought for $2 billion in 2014. With the exception of a few scattershot efforts like a 2011 consent agreement with the FTC, this growth has come with next to no oversight. That’s a pretty massive disconnect.

“The world has never seen the network effect as powerfully exhibited as with Facebook,” says Dave Roux, a veteran technology executive and investor. “The bigger it gets the better it gets and the more powerful it gets. Unfortunately, you have a toxic combination with this massive scale and one person [Zuckerberg] completely in control. It’s very much like a corporate North Korea.”

Lina Khan, an academic fellow at Columbia Law School and a senior fellow at the Open Markets Institute (OMI), an anti-monopoly think tank based in Washington D.C., notes that most of the major concerns about Facebook including privacy and national security are “heightened because of Facebook’s market power” and scale. “Many of its problems stem from its dominance and business model,” Khan says. “Facebook’s scale coupled with its business model are dangerous.”

And Facebook’s market share continues to grow. According to a new report by the OMI: “…Facebook had 72% of the $25.6 billion share of revenue from social networking sites. (LinkedIn was a distant second at 11%, followed by Twitter at 6% and everyone else with 11% combined.) In 2012, Facebook had a 61% share to LinkedIn's 14%.”

Given that bad actors (Russian agents, white supremacists, and proponents of ethnic cleansing in Myanmar, for example) have used Facebook’s platform to foist their agendas on our society, and given Facebook’s ineptitude and reluctance in responding to these threats, lawmakers in Washington are increasingly up in arms. Senator Mark Warner of Virginia and Congressman David Cicilline of Rhode Island, who both play key oversight roles on the Senate Intelligence Committee and the House Judiciary Committee respectively, have strongly criticized the company.

Cicilline has tweeted his displeasure over Facebook on numerous occasions.

In a recent interview Cicilline told me that Facebook has “an alarming concentration of economic power,” and had engaged in “a disturbing set of tactics that recalls big tobacco.”

As for Warner, he told me at Yahoo Finance’s All Markets Summit in Washington this past November, “…the notion that [Facebook is] going to be able to self-regulate themselves out of this just doesn’t cut it.”

A simple, yet radical solution—break up Facebook

A reckoning of some sort is coming. The question really is: What would be the best outcome not just for customers, employees and shareholders, but given Facebook’s impact on our society writ large, for all Americans?

First, let’s take a step back. Critics have raised questions about Facebook practices in several broad and interconnected areas including privacy, censorship, national security, and market power/antitrust. This has made forming a regulatory consensus difficult because usually each lawmaker focuses on one set of problems and not the big picture. For instance, GOP congressmen lambast the company for stifling conservative voices (which may or may not be accurate), while the Senate Intelligence Committee is focused on Russian security forces using Facebook to influence elections. It’s hard to imagine left-leaning Cicilline, who’s concerned about Facebook’s market power and use of customers’ data, working with Senator Ted Cruz, who’s slammed the company because he says it’s biased against conservatives.

On the one hand this makes things incredibly messy for Facebook—facing off against myriad critics with different agendas—but on the other hand it has allowed the company to effectively divide and conquer its opponents. However, just because its critics are uncoordinated, doesn’t mean these problems will go away for Facebook. In fact it may make them fester.

So again, how best to proceed?

There are a number of proposals on the table, which include a privacy bill of rights, government oversight, and tighter regulation a la Europe’s GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation). But really these are essentially piecemeal solutions that address the aforementioned issues in a select fashion. To cobble together a comprehensive solution would require many or all of them to be adopted, which is unrealistic. I do think however, there is one simple, admittedly radical, remedy that would potentially resolve all of Facebook’s problems.

That is: Break up Facebook.

I know what you’re thinking: “We’ve heard that before.” And, “It will never happen.” Or, “What good will that do?” And it’s true that even outspoken critics like Cicilline told me that breaking up Facebook is “not in Congress’s purview and a solution of last resort.” Yet I think there’s a compelling case to be made.

Breaking Facebook into competitive social media platforms would create instant competition in the social media business, which would allow the marketplace to reward the separated companies by best practices. For instance the company with the best user privacy protocols might attract the biggest audience.

The idea has caught the attention of some on Wall Street. “If you have separation, let’s just say of the three largest platforms Facebook owns—Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp— [some also include Messenger and Oculus Rift as other potential stand-alone platforms] certainly under different management and in a competitive construct they would be fiercely competitive for users. And it could change the way that the businesses are run,” says Scott Devitt, an analyst with Stifel. “In the end, I think a competitive environment can be good for owners of companies and users of companies.” The breakup of Facebook “would put the separate companies on longer term paths that would diffuse some of the issues that exist today around lack of competition, antitrust oversight, and regulatory,” Devitt says.

Columbia Law School professor Tim Wu, author of a new book, “The Curse of Bigness,” that essentially calls for a break up of Facebook, tells me that Instagram and WhatsApp “could position themselves as the anti-Facebook.” Wu says that Facebook’s mergers with these companies was “illegally consummated” because antitrust authorities in both the U.S. and the UK “did not have the tools to understand the markets or the stakes.”

The historical argument for breaking up Facebook

Longstanding Silicon Valley investor Roger McNamee, who chronicles his transformation from Facebook booster to Facebook loather in his soon-to-be published book “Zucked: Waking Up to the Facebook Catastrophe,” notes there is a precedent for breaking up big companies in the U.S. where all constituents make out for the better. “Antitrust is better than censorship because antitrust is growth,” McNamee says, pointing to the breakup of AT&T in the 1980s as being a huge win for shareholders.

In 1992, Fortune did a rundown of the common stockholder’s equity in old AT&T versus post-breakup AT&T. The article says: “The market value of AT&T's common stock just before the settlements were announced in January 1982 was $47.5 billion. In late June of this year, the market value of the eight successor companies together—the stripped-down AT&T, plus Ameritech, Bell Atlantic, BellSouth, Nynex, Pacific Telesis, Southwestern Bell, and US West—came to no less than $180 billion. Some of that gain reflects the billions of earnings that the companies have retained: The common stockholders' equity, or book value, of the seven Baby Bells plus AT&T is around $27 billion bigger than AT&T's was before the breakup.”

Even more significantly, the overall economy benefitted as the breakup ushered in discounted long distance and greatly sped up the advent of wireless telephony.

Going further back into American history, the breakup of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil of New Jersey into 34 entities in 1911 similarly unleashed a boon for shareholders and for the greater economy.

Tim Wu tells me he met with the Justice Department in June 2018 to warn it about Facebook’s dominance. DOJ’s response? “They gave me the impression that they weren’t there to sit on their hands,” Wu said.

Facebook declined to make any executives available to comment, but a spokesperson sent an email saying:

“Facebook operates in a fiercely competitive environment where people use our apps at the same time they use free services offered by many others. For every service offered on Facebook and our family of apps, there are three or four competing services with hundreds of millions, if not billions, of users. Importantly, under one roof, we’ve been able to better fight spam and abuse and build new features much faster, providing people with more useful products and services.”

The law is on Facebook’s side, for now

But let’s get real.

Siva Vaidhyanathan, the Robertson Professor of Media Studies and director of the Center for Media and Citizenship at the University of Virginia, says “…it would be crucial to break up Facebook, because as of now there is no real competition and no inclination in Silicon Valley to start up a new competitor.” Vaidhyanathan says that realistically, however, the chances that the Justice Department would take on the breaking up Facebook right now are slim. “Antitrust has been degraded for nearly 40 years,” he says, pointing out that DOJ now looks only at consumer welfare, meaning prices, not all the other problems that market dominance can bring. “We need new law review articles, new clerks, new case work and that would take years,” he says.

Facebook is well aware that the current state of antitrust law benefits its position. A Facebook pr person pointed me an op-ed piece in “The Hill,” written by David Balto, a former policy director at the Federal Trade Commission and Matthew Lane, outside counsel to the Computer and Communications Industry Association, which criticizes those like Vaidhyanathan and Wu who would restore and or expand anti-trust so that it could theoretically take on Facebook as “hipster antitrust,” that “has fixated on antitrust law as panacea for all the worlds ills.” (The New York Times recently published a story describing the FTC as an entity that many say has been far too cautious in overseeing Facebook and other social media giants.)

One possible source of change could be independent directors of Facebook; a group that includes White House veteran Erskine Bowles, former American Express CEO Ken Chenault, and Gates Foundation CEO Susan Desmond-Hellmann. Bowles was reportedly angry at not being informed of problems at the company. “If you’re associated with a tire fire of a situation and not associated with a solution ... independent directors [could] ... threaten to resign at some point if Facebook doesn’t do what independent directors think is right,” says Brian Wieser, an analyst with New York City-based equity research firm Pivotal Research Group. But asking directors to force a company to break itself up would be unrealistic, never mind unprecedented.

A tough pill to swallow

The ultimate change agent would be Zuckerberg himself. But is it possible that he would have the vision to see that breaking up Facebook would result in the best outcome for Facebook, oh and, by the way, for America? Not likely to be perfectly honest.

Wieser with Pivotal Research agrees that a breakup would be tough for Zuckerberg to swallow. “I assume someone in that position would generally not want to be told what to do, for starters. If you’re them, the top management, you genuinely believe you haven’t done anything wrong. You genuinely believe you’re doing good for world. If you believe in doing what’s right, why wouldn’t you fight it?”

Right, it becomes an ego thing really, even though remember that Zuckerberg would likely make out financially in a big way. Says Devitt: “If separation happened with Facebook, you’d have the opportunity to value entities separately, which on a stand-alone basis one could conclude the pieces would be worth more than they’re valued together today. It could be a positive outcome as it relates to shareholders. Think of the company’s shareholders wanting to make money off of the paper they own, which would benefit Zuckerberg the most as the largest shareholder.”

So sure, Zuck would get even richer. But with a net worth of some $50 billion, that’s not why he’s getting out of bed in the morning. So what if Mark Zuckerberg thought even bigger? What if he would imagine the innovation and growth that would occur if Facebook were broken up, like AT&T or Standard Oil? What if Facebook’s breakup ushered in the next internet revolution—and Zuck were the person responsible for it? Contrast that with the current scenario, where Zuckerberg and his lawyers will likely be fighting enemies and regulators for years and years—and most importantly, not participating in and shaping the future of the digital media, social networking, and the internet.

That’s why Mark Zuckerberg should on his own, proactively, break up Facebook. For himself. For the company. For all its constituents. For all of us.

It’s a huge, huge call. But it’s the right thing to do.

*Facebook’s mission statement used to be: “Making the world more open and connected.” Two years ago the company changed it to: “To give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together.”

Andy Serwer is Yahoo Finance’s editor-in-chief.

Read more:

Imagine Facebook without the ads but with a monthly fee

Tech companies are suffering from a success delusion

Mark Warner: This will ‘send a shiver’ down the spine of Facebook, Google, and Twitter