Studies contradict what Mark Zuckerberg is saying about Facebook

In the wake of Donald Trump’s victory in the presidential election, Facebook has become a major focus—for all the wrong reasons.

Throughout the campaign cycle, fake news headlines appeared on Facebook, especially after the company fired its Trending Topics team in August; headlines like “Pope Francis endorses Donald Trump,” to name one example. (To be sure, fake news is not only a problem on Facebook; at the moment, Google’s top election story says Donald Trump won the popular vote, which is not true.)

Now media outlets from the New York Times to the MIT Technology Review are wondering just how much those fake headlines influenced the election. New York Magazine put it more bluntly than most, with the headline “Donald Trump won because of Facebook.”

It’s hard to prove that definitively. But the noise got loud enough quickly enough that Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg felt compelled to post a long statement about it (on Facebook, obviously) on Saturday.

“After the election, many people are asking whether fake news contributed to the result, and what our responsibility is to prevent fake news from spreading,” Zuckerberg wrote. “Of all the content on Facebook, more than 99% of what people see is authentic. Only a very small amount is fake news and hoaxes. The hoaxes that do exist are not limited to one partisan view, or even to politics. Overall, this makes it extremely unlikely hoaxes changed the outcome of this election in one direction or the other.”

So, Zuckerberg is suggesting that less than 1% of content on Facebook is fake (if his term “authentic” does in fact mean factually correct); that it doesn’t come from one political side more than the other; and that it is “extremely unlikely” it had an impact on voters.

But a number of different studies call Zuckerberg’s stance into question.

Sources of misleading news: right-wing or left-wing

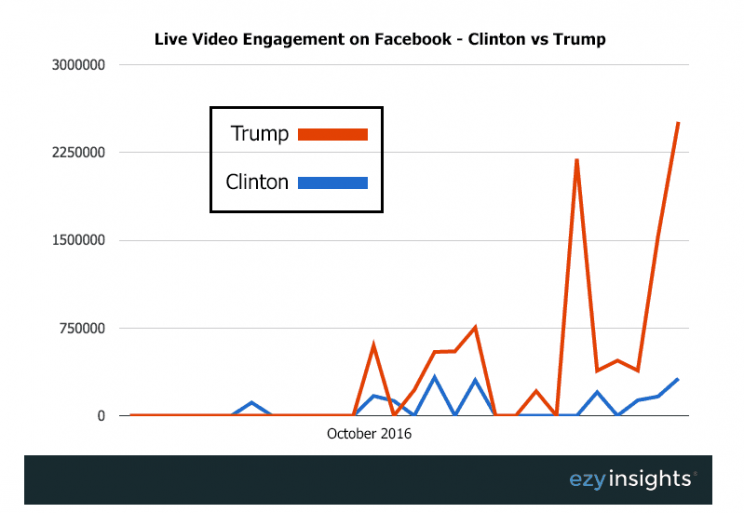

Before the election, a Nov. 1 report from social analytics firm EzyInsights showed that Trump’s campaign utilized Facebook much more successfully than Clinton’s. Trump posted live video and native video to Facebook more frequently (and, interestingly, more erratically, which worked), and saw higher engagement on those videos. After Trump’s win, it’s hard to argue his use of Facebook didn’t help.

Now EzyInsights has shared new data with Yahoo Finance on the frequency of Facebook posts from certain media outlets. The data shows a “dramatic rise,” as the election neared, in the frequency and popularity of posts from Fox News, Breitbart, Conservative Tribune, and other overtly right-wing outlets. There was not as much of an upswing in content from left-wing publishers, though Steve El-Sharawy of EzyInsights cautions, “There aren’t necessarily the equivalent number of staunch left-wing publications that we’re aware of or perhaps even exist.”

EzyInsights also discovered that Breitbart was the No. 3 biggest gainer during the election cycle in Facebook engagement. USA Today grew the most, followed by Yahoo News. The only publisher to lose engagement during this time was CNN. “Facebook amplifies the more extreme news sites on both ends of the spectrum,” notes El-Sharawy. “We are seeing those publishers further to the left and right of mainstream getting the larger gains.”

It’s also not unrelated that an Anti-Defamation League report on the rise of anti-Semitic abuse on Twitter concluded that “a disproportionate volume” of the abuse came from Trump supporters.

Trump’s campaign posted more content to Facebook, and right-wing outlets posted more content to Facebook. It’s hard to wave off the obvious correlation between volume of Facebook posts and the final election result.

Yes, social media users are influenced by social media posts

Two days after the election, on Thursday (before he eventually posted the longer statement on Saturday), Zuckerberg said at a Q&A that the idea Facebook could influence voters is “pretty crazy.”

But in a Nov. 7 Pew Research report, 20% of adults said that a post on social media has changed their view on a certain issue. Of those, 17% said social media has changed their view of a specific candidate.

What that shows is that a segment of Facebook users who look to the social media giant for news can indeed be influenced politically by the news stories they see, whether those stories are false or true.

FB + Twitter cannot take credit for changing the world during events like the Egyptian Uprising, then downplay their influence on elections

— this is not normal. (@karenkho) November 13, 2016

As data scientist Patrick Martinchek writes on Medium, “Most headlines are browsed, not clicked… Because of this, the headlines frame our positions on topics without even having to read the content… with respect to politics, this news feed browsing behavior creates an electorate that can become dangerously uninformed.”

And many, many people get their news on Facebook.

44% of adults get news on Facebook

Another recent Pew Research report from May 26 showed that 62% of US adults get their news from social media—maybe not all of their news, but at least some portion of it. Within that group, 66% of Facebook users get news from Facebook, and 59% of Twitter users get news from Twitter.

With Facebook’s user base having ballooned to 1.8 billion monthly active users, that 66% translates to 44% of all US adults, a staggering figure.

So: 44% of all adults look to Facebook for news; 20% of them say social media posts are capable of changing their views on a political issue; and more of the stories posted on Facebook this cycle, real and fake, came from right-wing outlets.

Taken together, it all suggests Facebook had a much larger role in the election than Mark Zuckerberg would like to admit.

And it also underscores that Facebook has become a media company; the fact that Facebook is not the creator of the content it distributes doesn’t negate that.

Last month, speaking at a conference, COO Sheryl Sandberg was asked “if Facebook is acknowledging that it is a media company, and not just a technology platform.” Sandberg avoided, saying, “Facebook’s a platform for all ideas and it’s really core to our mission that people can share what they care about on Facebook.”

During the election cycle, it was also a platform for some fake ideas, unfortunately. And even if the fake stories were only 1% of all stories (a figure many people doubt), 1% of all stories on Facebook represents quite a lot of stories.

Poynter writes that it’s impossible for Zuckerberg to know how much of the content on Facebook is real or fake anyway. “The claim that 99 percent of content on Facebook is authentic is itself a fake,” Walter Quattrociocchi, a professor at the IMT School for Advanced Studies in Italy, told Poynter.

Zuckerberg, in his Facebook post, appeared to say Facebook will do more to cut down on fake news, but the promise was noncommittal: “We have already launched work enabling our community to flag hoaxes and fake news, and there is more we can do here. We have made progress, and we will continue to work on this to improve further… We hope to have more to share soon, although this work often takes longer than we’d like in order to confirm changes we make won’t introduce unintended side effects or bias into the system.”

On Monday, citing anonymous sources, Gizmodo reported that Facebook has the ability to cut down on fake news, but hesitated to enact it because it did not want to upset conservatives and look politically partisan. Facebook executives, Gizmodo says, “were briefed on a planned News Feed update that would have identified fake or hoax news stories, but disproportionately impacted right-wing news sites by downgrading or removing that content from people’s feeds. According to the source, the update was shelved and never released to the public.”

If that is true, Facebook must make that update immediately.

—

Daniel Roberts is a writer at Yahoo Finance, covering sports business and technology. Follow him on Twitter at @readDanwrite.

Read more:

Facebook and Twitter played very different roles in the 2016 election

The good and the bad of streaming the debates on Twitter and Facebook

What it was like to listen to Trump and Clinton debate on the radio