The IRS pays whistleblowers to turn in tax-evaders

Since President George W. Bush signed the Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006, the IRS has had a program that rewards Americans who inform the agency on tax dodgers. In its first decade, the program has helped the IRS recover $3.4 billion, and resulted in payouts of $465 million to whistleblowers.

Here’s how it works. Someone files an IRS Form 211, an “Application for Original Information” that’s one page long, with the IRS. It contains information about the taxpayer (or tax avoider) and the nature of the violation to the extent that they know it, and there’s a place to describe how you know the individual or company.

Then you wait for the 37-employee IRS Whistleblower office to look into the matter.

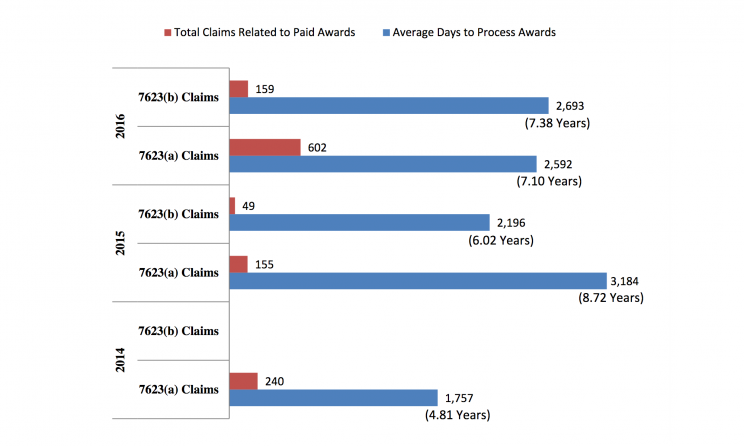

The wait can be long, and it generally takes 5 to 7 years before the person or company being investigated exhausts all the appeals that need to happen before a collection can happen—if the IRS decides to proceed at all. They don’t have to take the case.

But it might be worth it to try. If the amount of tax avoided—plus interest and penalties—exceeds $2 million and the person under investigation has made more than $200,000 in one of the years in question, the reward is 15% to 30% of the amount recovered. If the amounts don’t meet that standard, there may still be rewards, but they max out at 15% and are given at the IRS’s discretion (which could nothing).

Recent cases include a former JPMorgan (JPM) employee who blew a whistle on hundreds of millions of alleged tax violations dealing with retirement accounts. Public-private partnerships also provide plenty of opportunity for tax issues where a whistleblower can collect. For the IRS, whistleblowers and assisting lawyers, the higher the bounty the better, so people blowing a whistle on corporations are more common. However, it does happen for individuals, too.

“Most of our cases are against corporations,” said Eric Young, a whistleblower attorney in Philadelphia who secured the first payout from the Whistleblower Program in 2011 for $4.5 million. “Occasionally, we will represent someone [with information on] a high-net-worth individual, like offshore tax-evasion issues if it’s really substantial.” For his first case, the client, who remained anonymous (as most whistleblowers choose to be), had been an accountant at one of the country’s largest financial firms.

High bar to clear

“We only take a small fraction of the cases that people come to us with,” Young told Yahoo Finance. Not all the cases they turn away are bad, but they have strict criteria because of the volume they can take.

“One of the problems with the program is the payouts are pretty infrequent compared to the number of cases,” said Young. “There’s a number of lawyers I know in the whistleblower space that have made a business decision not to do IRS whistleblower cases.”

Whether the IRS even decides to take the case is a big question, and someone who wants to inform on their neighbor needs actual information, not just speculation because they have a fleet of Ferraris and a teacher’s salary. For this reason, and the sheer complexity of the process, many whistleblowers hire an attorney like Young to help them make the best case possible before it gets to the IRS, especially if they fall in the big fish category.

So far, Young’s firm has seen three large payouts. Around 20 claims are still active, representing anywhere between $10 million to $1 billion in tax evasion.

‘Significant federal tax issue’

Overall, however, most claims do not make it. Last year, 12,395 claims brought to the IRS failed to be specific or credible. In the IRS’s words, “We are also looking for a significant federal tax issue—-this is not a program for resolving personal problems or disputes about a business relationship.”

These difficulties, as well as the IRS’s discretion as to what they’ll take means that lawyers like Young don’t really take smaller cases that fall into the first sub-$2 million category. “The dollars aren’t there,” he said. Another lawyer at his firm likened those cases to lottery tickets, as the chances are even lower to win. However, he said the firm does counsel people on how to proceed on their own if they wish.

For fiscal year 2016, the IRS said $61 million was paid out to 418 tax whistleblowers, an increase over last year’s 99 awards but a decrease in dollars, which topped $103 million in fiscal year 2015. That’s because 2015 had more high-profile cases and ultimately a higher dollar amount brought in under the program.

Risk of retaliation against whistleblowers

One issue that can come up for whistleblowers is the matter of protection from retaliation, something that can be a big risk when the stakes are at any size. “There is technically no anti-retaliation under the IRS whistleblower law unlike other whistleblower laws,” said Young. “That’s why someone should not try to do that on their own if that’s a concern to them. Having a lawyer who knows their way around this issue is critical to make sure not retaliate against.”

Young praised the IRS’s excellent confidentiality practices. He has been involved in many cases in which the client was still on the inside, unknown to the investigated company.

The risks may diminish: With input from the Government Accountability Office, the program is considering implementing legal protection for whistleblowers as well as fines or other penalties for whistleblowers who improperly disclose taxpayer information they get from the IRS during an investigation they’re involved in.

This could make a difference, if more people come forward. According to IRS estimates, $458 billion of revenue is lost every year to tax evasion. That loss just makes taxes higher for the rest of us.

Ethan Wolff-Mann is a writer at Yahoo Finance focusing on consumer issues, tech, and personal finance. Follow him on Twitter @ewolffmann.

Read more:

The CFPB has returned $12B to consumers. Republicans want to kill it

Chase’s Sapphire Reserve is very worth it, even with its slashed bonus

Veterans group uses Trump’s well-known habits to target him with an ad

President Trump’s predecessors learned about tariffs the hard way

51% of all job tasks could be automated by today’s technology