These people are most likely to lose their jobs first in a recession

No one can predict how severe an economic downturn might be – and which workers are most at risk of a job cut. But it’s useful to put historical data in context.

While having at least a bachelor’s degree does reduce the likelihood of getting laid off, all college graduates are not treated the same by employers.

Young college graduates will likely be the first to receive pink slips in the next recession. That has been the case during the Great Recession, which lasted from December 2007 to June 2009, and during the 2001 recession which Americans endured for eight months.

Brookings Institution economist Harry Holzer says newer college graduates are among the first to be targeted by employers in a recession, because they are the most marginal people in the workforce, having just entered it. "Young people get hit the hardest during a recession and that will include young college grads. It will take them longer to find any job, and it will take longer for them to find the jobs they really like in terms of beginning a career," he says.

Youth is a factor that tends to work against workers in a recession. People who have recently entered the labor market “are most vulnerable to economic shock, by comparison, to people who are more established in their careers,” says Hamilton Project policy director Ryan Nunn. They “may have a more durable relationship with a particular employer and maybe can ride out the recession a little more easily.”

During the Great Recession, the unemployment rate for workers aged 20 to 24 with a bachelor’s degree rose from 5.4% in 2007 to 8.5% in 2009, according to the BLS. It was much lower for older college graduates with the same education during the financial crisis – it went from 2.2% in 2007 to 5.2% in 2009.

Although the recession officially ended in June 2009, the unemployment rates for both groups were even higher in 2010. Unemployment for young college graduates was 9.2%, and 5.4% for older college graduates.

People have cause to be a least a little concerned. A few signs have been bubbling up that suggest a less-than-rosy economic picture – both in the US and globally. U.S. manufacturer growth slowed to the lowest level in almost 10 years in August, according to results from IHS Markit data. And last week the Federal Reserve reported that manufacturing output fell 0.4% in July from a month earlier, and was 0.5% lower compared with a year ago.

Not to mention a closely watched part of the yield curve inverted on Aug. 14. (The yield curve is a powerful predictor of an economic downturn, and an inversion has preceded each of the last seven recessions dating back to 1969.)

These factors have been fueling recession fears, and with it memories of the millions of layoffs that hit U.S. workers a decade ago during the Great Recession.

Whenever a recession does hit, it’s important to remember, it wouldn’t necessarily be like the last one in 2008. At its lowest point, in February 2010, U.S. employment had declined by 8.8 million jobs from its pre-recession peak, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Monthly job losses averaged 712,000 from October 2008 through March 2009 – the most severe six-month period of job losses since 1945.

Lingering impact of 2008 financial crisis

The 2008 recession wreaked havoc on the financial well-being of many workers by delaying the trajectory of their careers and costing them lost wages. Millennials who graduated into the recession faced “large, negative, and persistent effects on their incomes,” according to a report by the Hamilton Project at Brookings Institution, “The Damage Done by Recessions and How to Respond.”

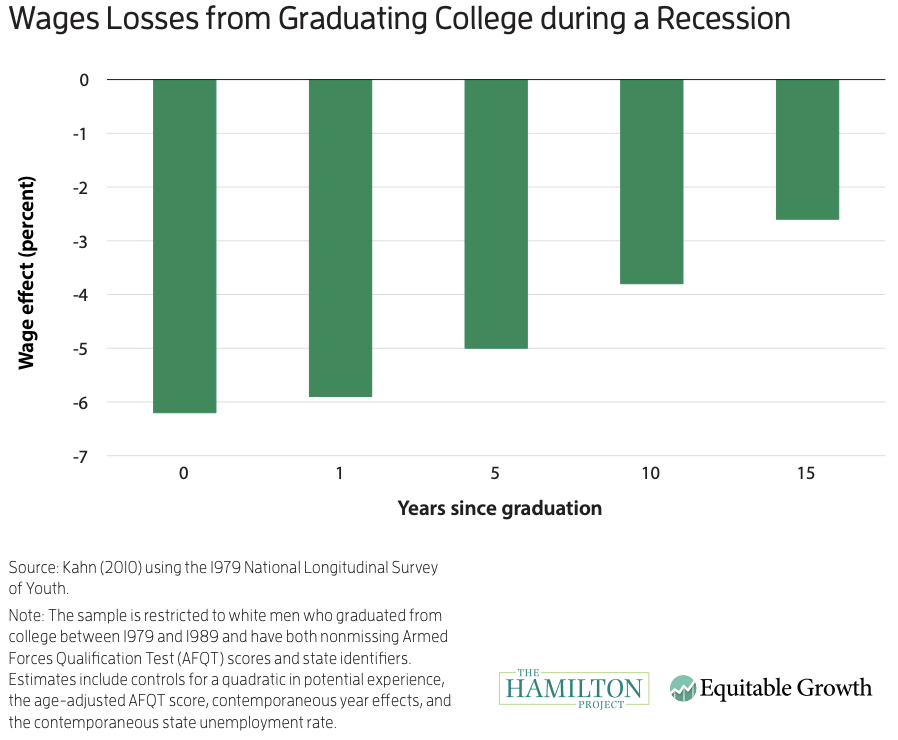

Young people who graduate in a recession face a more than 6% wage loss in that initial year of graduation. That economic loss slowly subsides over time. Five years after graduation, though, they still earn 5% less than those who graduated during non-recessionary years, according to Brookings.

“What’s striking is that those wage losses don’t disappear immediately. Those are very persistent. Fifteen years after graduation, in a recession you’re still talking about a non-trivial wage decline,” says Nunn.

More from Sibile:

How Fed Chair Powell can avoid a stock market nightmare

Why Trump’s efforts to keep immigrants out hurts the U.S. economy

Trump delays tariffs to appease Christmas shoppers