'A fight at every step': Trump's wall will have to battle the people who live there

President Trump declared a national emergency in February in his most direct attempt to secure the funding for his signature campaign promise: a “big, beautiful” wall along the U.S.-Mexican border.

But even if he gets the billions of more dollars he would need to be the border wall — which is actually a combination of vehicle barriers and pedestrian fencing — the massive construction project faces a major hurdle, according to legal experts: The people who live along the border may not want to give their land up to the government.

The circumstances raise the issue of eminent domain: That is, the power of the government to take privately owned land and convert it to public use — with compensation to the landowners.

Eminent domain is a “big impediment to the wall and has been an impediment to fencing,” Elaine Kamarck, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, told Yahoo Finance. “People don’t like their land taken, and usually don’t think they’re getting what the land is worth. … The whole thing is going to be a fight, and it’s going to be a fight at every step of the way, with a lot of things going to the court.”

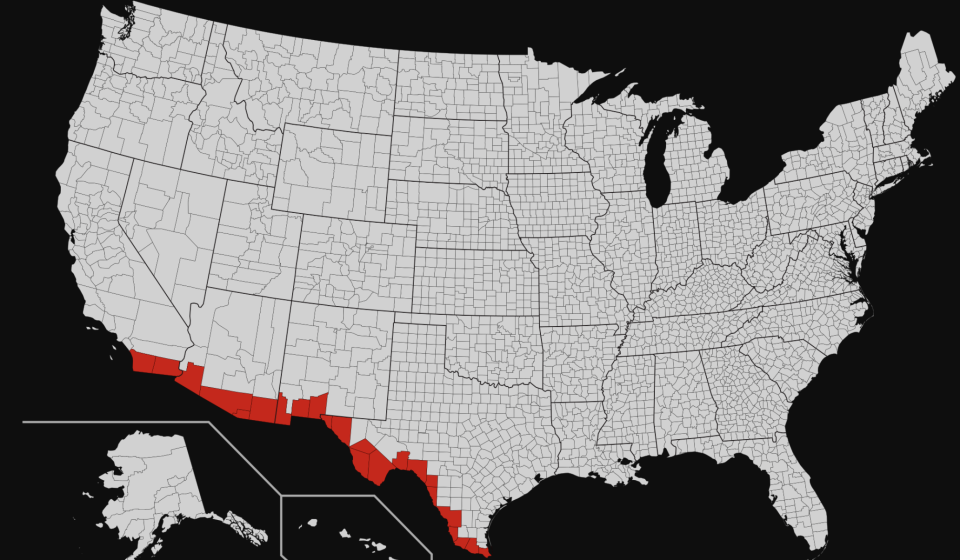

According to Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, which looked through property records from all but one of 22 counties along the U.S.-Mexico border, “less than a quarter of the top 200 landowners currently have a border barrier on their property or on adjacent federal land.”

CNN recently reported that the Trump administration has sent letters to landowners in California, New Mexico, and Texas to notify them that the government will be surveying their land for constructing more of the border wall.

“Government officials uniformly underestimate how difficult and time-consuming it will be to use eminent domain to take property,” Robert McNamara, a senior attorney at the Institute for Justice, told Yahoo Finance. “It’s also true that the courts have routinely held that the power of eminent domain belongs to Congress and can only be used by the executive to the extent Congress has delegated it to that authority.”

Eminent domain traditionally faces ‘tons of legal challenges’

One of the most notable cases over the use of eminent domain was Kelo v. New London, in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the New London Development Corporation could use land in Fort Trumbull, Conn., because it was for economic development. As a result, 15 properties were relinquished to the state.

“That’s a huge problem every time a government tries to use eminent domain,” Kamarck said. “They get tied up in tons and tons of legal challenges for years and years and years.”

Luke Ellis, a Texas-based attorney who focuses entirely on eminent domain matters, recalled one of his clients who was contacted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers about his property being surveyed for the purposes of border wall installation.

“Is there a viable challenge to the taking? I believe there is,” Ellis told Yahoo Finance. “From a very high level, a condemnation case breaks down into two components. All of this is governed by the 5th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and by many, many cases that have interpreted the provisions … which basically says, ‘nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation.’”

McNamara stressed that Congress would be key to any claim of eminent domain.

“There’s obviously a debate about whether Congress has authorized the ‘emergency’ use of funds to construct the wall, but in the context of eminent domain, the courts have been clear that uncertainty about whether Congress has authorized eminent domain has to be resolved in favor of the property owner, not in favor of the government,” he said.

‘How much money does the government owe you’

In any eminent domain case, there are two basic questions, according to McNamara.

“The first is what’s called the right-to-take question: Can the government use eminent domain?” he said. “And the second is the just compensation question: How much money does the government owe you for using eminent domain?”

That second issue — the idea of just compensation issue — can be particularly tricky.

“The theory is: Your just compensation is supposed to be what a willing buyer would pay a willing seller on the open market,” McNamara said. “And that’s something of a fiction, because we’d know at the onset just by the fact the government’s using eminent domain, we don’t have a winning seller.”

He added that if someone wanted their property to be sold for fair market value, there would be a for-sale sign at the front of their house.

“So, by definition, everyone who is the victim of eminent domain is losing something in terms of the value of their property,” McNamara continued. “They’re going to be underpaid if they’re awarded fair market value, because they didn’t want to sell their property for fair market value.”

Ellis put it in simple terms: “Let’s say you’ve got a property owner who owns property right up the Rio Grande and it’s 100 acres. And they put the fence, the border wall, through the middle portion of the 100 acres. Now let’s assume they need 10 acres for the actual area — the footprint of where they’re going to install the border wall and some buffer coming off of it.

“Well, they’ve got to pay for the 10 acres they take, but under that hypothetical, they also have to pay for the reduction in value, if you can prove it, to the remaining 90 acres.”

The march toward 1,000 miles

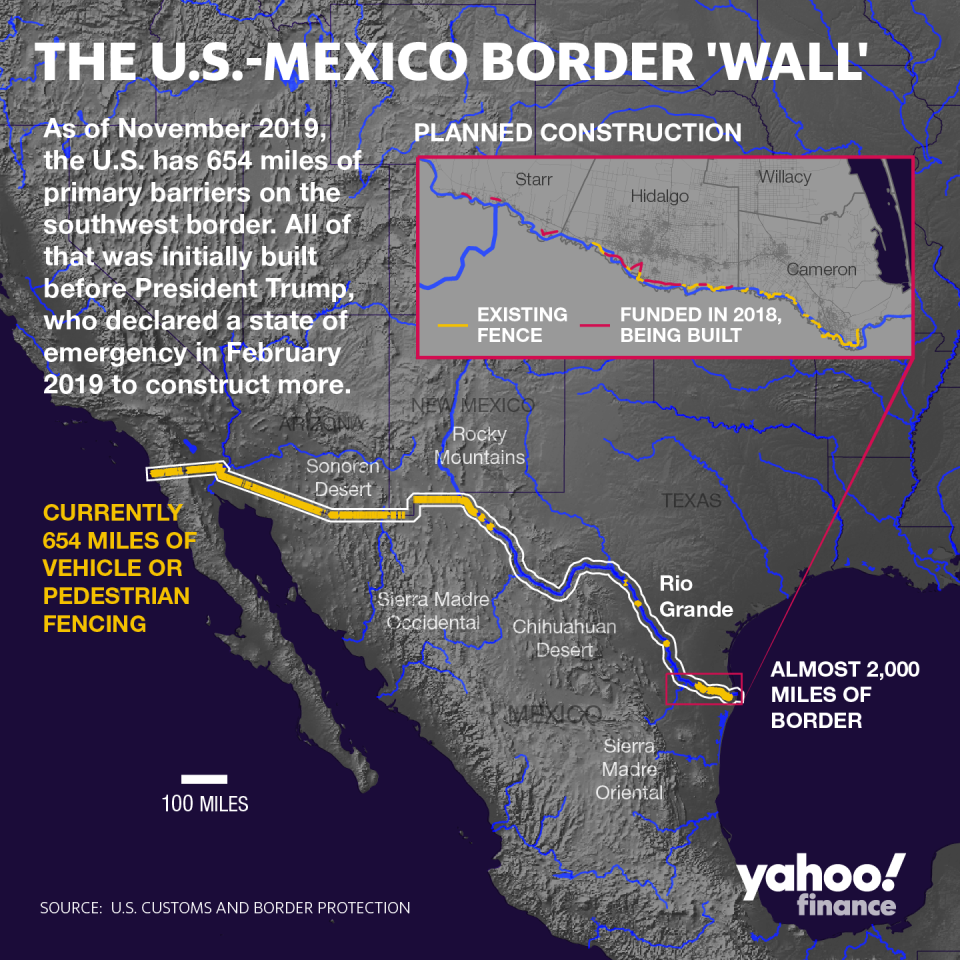

So far, there are 654 miles of border barriers. This includes 308 miles of pedestrian fencing and approximately 273 miles of vehicle barrier constructed prior to January 2017, along with approximately 73 miles of new primary border wall system to replace outdated signs since January 2017, according to CBP data. And, according to the data, “construction is currently underway in locations where no barriers currently exist, which will increase the total miles of primary barriers on the southwest border as construction progresses.”

In March 2018, Congress passed a $1.3 trillion spending bill that included $1.57 billion for border fencing and other related costs. That would bring the length of the barriers to 688 miles. After the partial government shutdown came to an end, Congress approved an additional $1.4 billion to cover 55 miles of new fencing, which would bring the total to 743 miles. On March 25, the Pentagon approved $1 billion for 57 more miles of border wall construction, which would bring the length to exactly 800 miles.

“When fully funded,” CBP stated in March 2018, “about 1,000 of almost 2,000 of the U.S. border with Mexico will have border wall and other critical infrastructure.”

All of the construction will inevitably require the usage of currently private land.

“You have to understand — when they build the border wall, they don’t put the wall right on the edge of the Rio Grande river,” Ellis said. “Because of floodplain issues, the river can rise and fall, so they always put the wall upland into the property by at least a few hundred yards — in some cases, more.”

So what will that mean?

“It means if you own that hypothetical 100 acres I’m talking about, and they take 10 acres to put the wall across your property, you may have 10, 20, 30 acres of land that’s now sandwiched south of the wall and north of the Rio Grande,” Ellis said. “That’s still technically U.S. soil, still technically your property.”

He continued: “Sometimes, the government will take what I think is an incredible position, that the land that’s now sandwiched between the wall and the river is worth just as much as before they ever built the wall. And I think that’s very inconsistent with how the market would react to the property. That’s part of what we fight over when we talk about just compensation. It’s that damages to the remainder issue.”

A recent NBC report stated that government attorneys may try to use the Declaration of Taking Act, “which could expedite the process for the government purchase of private land along the border.” In any case, private landowners will still have a say.

“It’s really important to emphasize that landowners do have rights in this process, even if the government doesn’t make it seem that way,” Ricky Garza, a staff attorney at the Texas Civil Rights Project, told Yahoo Finance. “Everyone has a right to due process in this country and everyone has a right to stand up for their land and their heritage. Even though these cases can go extremely favorable towards the government by the judges, everyone does have a right to their day in court.”

‘The price for this thing goes up even further’

The cost for the wall has been increasing, and “once you add in the fight over eminent domain and perhaps the need to placate some of these landowners, the price for this thing goes up even further,” Kamarck said. “A lot of the land along there isn’t very valuable … but there are families that have ranches there for generations and they’re not going to give this up easily.”

Garza recalled one client who has been battling an eminent domain case for over a decade.

“Nothing was built on her land because she’s been fighting it in courts,” he said. “And that case was first filed in 2008 and it is still unresolved as of October 2019. So that definitely isn’t the typical case, but it is possible because of some flukes in the law and because of choices the government’s made and in litigation, those cases will go on for years and years without resolution.”

Another thing to keep in mind, McNamara stressed, “is that at the receiving end of every single eminent domain action is a real human being who is going to lose property that they’ve worked extremely hard to own. And amidst all the political debates, we should never lose sight of flesh-and-blood property owners who are being deprived of their hard-earned property.”

Although it’s unclear whether or not the Trump administration will be successful in court with these eminent domain cases, Garza thinks it’s still worth a fight on behalf of the landowners.

“If enough people resist rolling over and giving their government their land for the border wall, it really will make the government realize just how complicated and costly an exercise this is,” he said. “When it started under the Trump administration, I think the government was imagining that they could use intimidation and tactics of confusion to make many people sign over their land without ever getting just compensation. And that’s how the government prefers to do things.”

Adriana is an associate editor for Yahoo Finance. Follow her on Twitter @adrianambells.

READ MORE:

Trump's border 'wall' is getting 57 miles longer — and the national emergency end game is in sight

National emergency: How Trump's 'wall' could actually be built after his 'VETO!'

Former DEA agent: Trump's wall will 'have very little effect on the flow of drugs'

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.