Trump is going after the open internet next

The Trump’s administration’s campaign to reverse President Obama’s tech-policy moves won’t stop with this week’s vote by the House to shut down internet-privacy regulations.

On Thursday, President Trump’s press secretary Sean Spicer made it clear that the legal foundation of net neutrality, which prevents broadband providers from limiting access speeds to certain sides, is also on Trump’s hit list.

In remarks opening Thursday’s press briefing, Spicer complained that the 2015 move to reclassify internet providers as common carriers — putting them under the same open-access principles as phone companies — “opened their door to an unfair regulatory framework.”

That makes the existing ban on internet providers blocking or slowing legal sites or charging them for faster delivery look even deader than they already do under Trump. And that elevates the risk that a site or app you like might have to pay off your internet provider, or that you’d have to pay more to visit or use it.

Revisiting “reclassification”

What Spicer had in mind is what telecom wonks call “Title II”—the legal framework from the Telecommunications Act of 1934 that covers telecom services that provide open-ended access instead of limiting you to a defined set of connections.

Why would Spicer, Trump or anybody else care? Because the FCC voted to put internet providers back into this category in 2015 after earlier attempts to write open-internet rules were defeated in the courts.

Those previous net-neutrality failures were rooted in the FCC’s 2002 move to classify cable internet providers as “information services,” a newer category that may best describe AOL’s traditional dial-up online service. The commission later put other broadband technologies into this same bucket.

That matters because, like any other agency, the FCC can’t write rules unless Congress passes a law authorizing it to do that.

And courts have repeatedly ruled that the rest of the FCC’s enabling legislation — in particular, the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which added the information-service category — doesn’t provide the authority needed to support meaningful open-internet rules.

What’s to like and hate about that

In his remarks, Spicer bemoaned the common-carrier rules, saying they treat ISPs “much like a hotel or another retail outlet.” That’s… an interesting comparison, but the more apt one would be to a phone company.

Net-neutrality opponents point to such Title II provisions as its requirement for “just and reasonable” pricing.

When the FCC enacted the net-neutrality rules, it ruled out rate regulation and many other forms of common-carrier oversight set out in the 1934 law, but it could change its mind later on. Re-re-classifying internet providers would ensure that a future FCC can’t do that.

But it also risks a new round of litigation and court defeats — one thing I’ve learned over the decade and change that I’ve been covering this issue is that Big Telecom’s lawyers don’t let up.

Advocates of rebooting net neutrality via a reclassification need to explain how this wouldn’t yield a repeat of history, since the Title II rules are the only ones to withstand a court challenge.

As Matt Wood, policy director of the liberal tech-policy group Free Press, told me in February: “You get a lot of Republicans saying they’ve always supported the principles of net neutrality — just not those pesky laws that make it a reality.”

Now what?

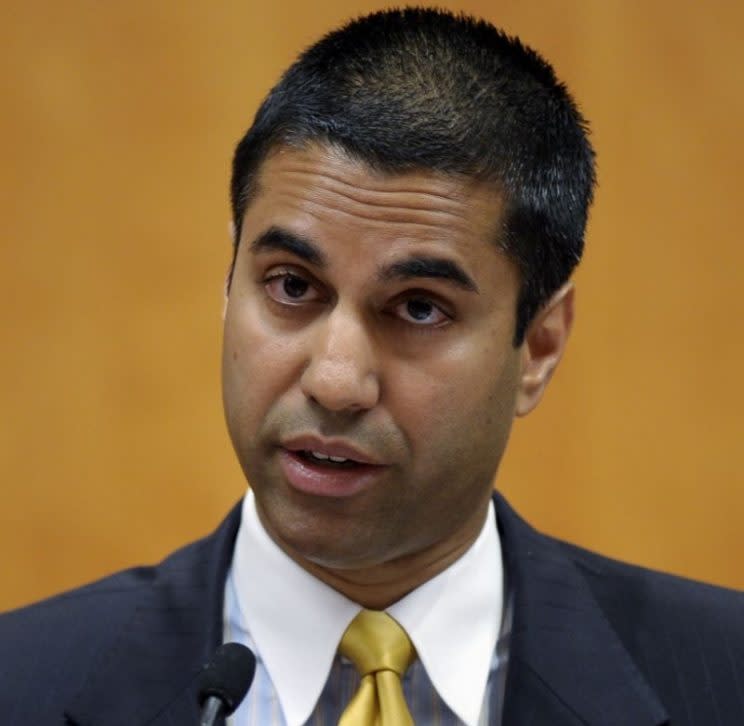

When FCC chair Ajit Pai said in February that the commission would no longer investigate wireless carriers exempting their own video services from their data caps, you could argue that this didn’t represent a huge change.

Remember, Pai’s predecessor Tom Wheeler had done little to halt the self-serving conduct of carriers offering their own video and music services for free without impacting users’ data caps. Competing services, meanwhile, could cause consumers to plow through their monthly data allotments resulting in overage fees.

But a complete reclassification would vacate all of the existing rules. If Pai stops there, an internet provider could, in theory, start blocking entire applications in the way that AT&T blocked Apple’s FaceTime video calling only five years ago.

That probably won’t happen with wireless carriers, thanks to fierce competition that’s led all of them to pitch increasingly generous unmetered-data offerings. It also seems unlikely with residential broadband firms, given public pledges from the likes of Comcast (CMCSA) to support open-internet norms.

But the lack of competition in residential high-speed internet access could tempt some smaller firms to exploit their liberated regulatory environment less blatantly.

Pai himself has voiced support for looser net-neutrality rules, but writing them would take a lot longer than zeroing them out — think a year or more.

“The Commission would have to initiate a proceeding, solicit comment and reply comments from stakeholders, digest and consider the merits of those comments from stakeholders and then construct a new order,” explained Public Knowledge associate counsel Kate Forscey. “It would take quite some time indeed.”

One opponent of the current rules suggested that the FCC would be better off with case-by-case enforcement, in which it would wait for individual site or app developers to call a foul on internet providers instead of telling ISPs upfront what they can or can’t do.

Hal Singer, an economist with the George Washington University’s Regulatory Studies Center, backed “a complaint-driven process” like how the FCC deals with complaints of cable operators discriminating against individual networks.

But whether we’re looking at lax enforcement of today’s rules, a new round of looser regulations or the FCC acting as a referee, it won’t be big-name video firms like Netflix (NFLX) that will suffer. It would be the small sites and apps without lawyers and lobbyists on call in Washington that stand to lose.

More from Rob:

Google’s chief internet evangelist seems nervous about Trump’s tech policy

Venture investor on Trump: ‘We are in an absolute unmitigated crisis’

The real lesson of Wikileaks’ massive document dump — encryption works

Email Rob at [email protected]; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.