The Trump tax cuts favor robots over workers

There’s no lobbying group for robots in Washington. Yet robots and other types of machines are shaping up to be big winners in the tax-cut legislation speeding through the House and Senate. And that’s troubling news for workers in manufacturing and other sectors.

In addition to slashing the tax rate on businesses, legislation in both the House and Senate would establish new incentives for investing in plants and equipment. That’s a traditional way of enticing businesses to generate more economic activity—which, in theory, creates more demand for workers and pushes up wages. But the traditional way may not apply any more.

“We are subsidizing an investment in robots, but we’re not subsidizing an investment in people,” says Edward Kleinbard of the USC Gould School of Law, former chief of staff for Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation. “We are putting our thumb on the scale to encourage investment in machines over humans.”

Before the digital revolution, it was generally true that when companies invested in new plants and machinery, the hiring of a lot of new workers typically followed. But that relationship has broken down. It takes fewer and fewer workers to operate the increasingly automated machinery on factory floors. Manufacturing output keeps going up, even when the manufacturing workforce is stagnant or declining. The trend is spreading to other sectors, such as retail, as software and machines become increasingly sophisticated.

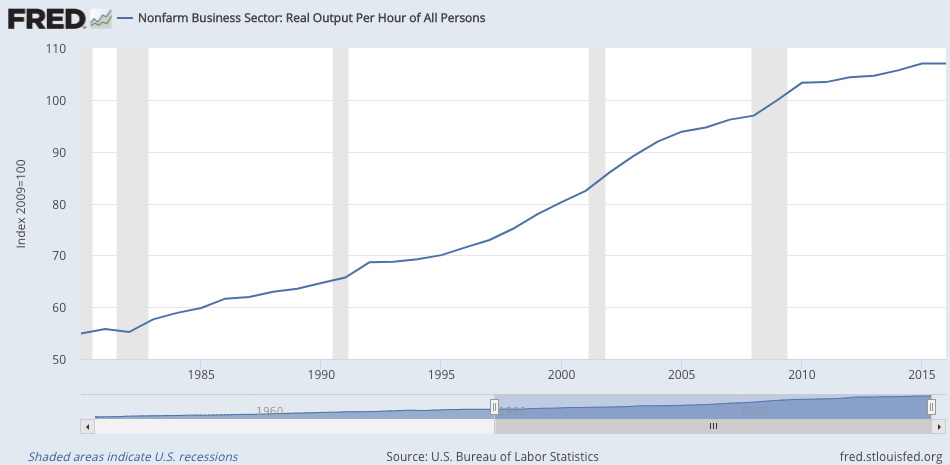

In economic terms, the problem is that growth in labor productivity is very weak, even as the economy grows. Here’s the trend since 1980:

Productivity growth is what helps workers earn raises and get ahead, since they become more valuable as output increases. Flat productivity growth, by contrast, helps explain why wage growth has been weak for the last two decades—and why many people feel they’re falling behind.

How to ensure a middle-class benefit

Both the House and Senate tax plans are heavily weighted toward business tax cuts, with about two-thirds of the net tax cuts in the Senate plan, and a bit more in the House plan, going toward businesses. Individual taxpayers get less than one-third of the benefit, and middle- and working-class taxpayers, get even less.

The Republican tax-cut approach relies heavily on “supply-side” changes that, in reality, have a dubious record. In theory, increasing the return on capital, which is what business tax cuts accomplish, leads to more investment that makes most people better off, eventually. That’s why Republicans claim their plan will save a typical family with two kids nearly $1,200 per year. Kevin Hassett, chairman of the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers, says the savings could eventually tally more than $4,000 per year.

But that depends on companies hiring workers much as they have in the past—in some cases, the fairly distant past, such as the 1980s, when assembly lines were still manned largely by humans. Workplaces have changed dramatically since then, and a lot more change is probably coming, as machines become increasingly capable.

There’s another way to make sure ordinary people benefit from a tax cut: Make the benefits of the cut trickle up instead of trickling down. In other words, cut taxes for the middle class—below a certain income threshold, say $200,000 for a family of four—and forget about cutting business taxes. Businesses might still buy robots, but they wouldn’t cut their tax bills by doing so, and the robots would have to compete with the humans fair and square.

Confidential tip line: [email protected]. Encrypted communication available.

Rick Newman is the author of four books, including Rebounders: How Winners Pivot from Setback to Success. Follow him on Twitter: @rickjnewman