Venture capitalist John Doerr: Theranos had the 'wrong goals'

If Theranos had approached its business goals differently, the health tech company might have avoided its dismal fate, which now includes founder Elizabeth Holmes and president Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani being charged with federal wire fraud.

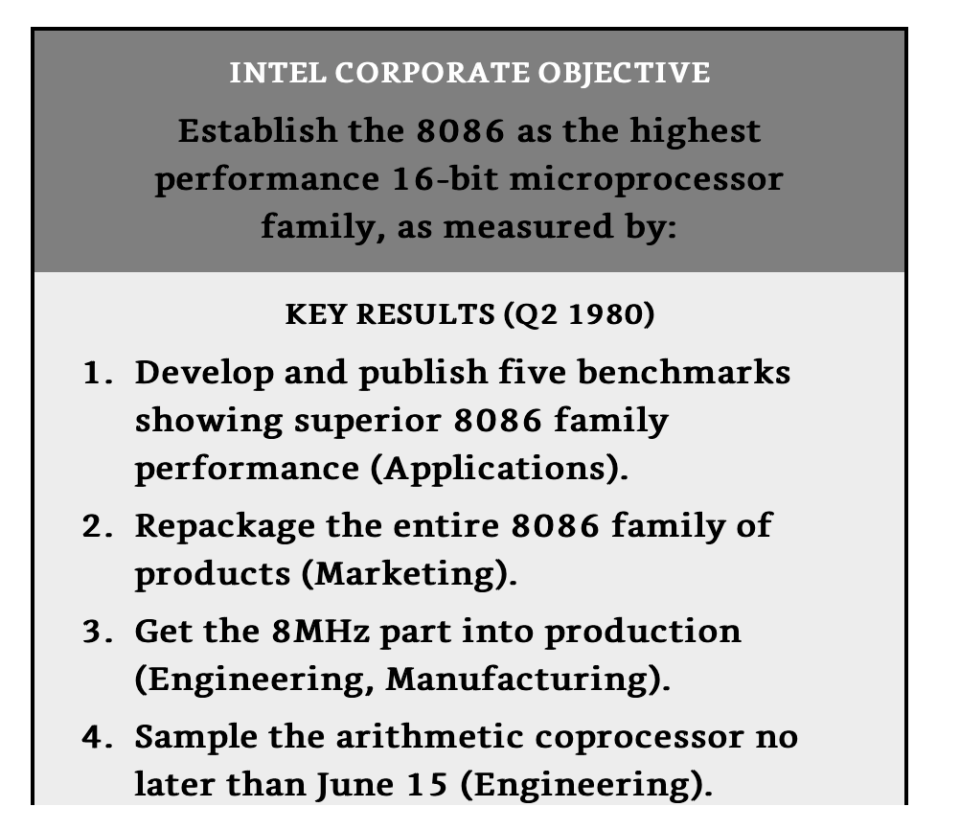

That’s according to John Doerr, chairman of venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers. Doerr’s newest book, “Measure What Matters,” explains how a goal-setting system called OKRs (“Objectives and Key Results”) helped leaders — Larry Page and Sergey Brin at Google (GOOG, GOOGL), Andy Grove at Intel (INTC), among others — achieve their short- and long-term goals and successfully grow their organizations in the process.

“They had the wrong goals. You see it in tech companies like Theranos and Zenefits,” Doerr said, referring to a health-benefits startup that was plagued by regulatory issues. “A good transparent use of goals and OKRs, and I dare say those wouldn’t have happened.”

A longtime venture capitalist in Silicon Valley, Doerr got his start in Silicon Valley at Intel as the company worked towards the release of its 8086 microprocessor. It was there Doerr observed former Intel CEO Andy Grove create and implement OKRs for the first time, which helped guide the company towards meeting its internal targets for the project.

Since then, Doerr has helped over 100 organizations — Intuit (INTU), The Gates Foundation, Bono’s One — deploy OKRs to help focus on and set a handful of concrete and aspirational goals on a quarterly and longer-term basis. In the case of MyFitnessPal, for instance, the fitness-focused startup in 2014 deployed OKRs of “helping more people around the world” as an objective with “key results” that included adding 27 million new users in 2014 and reaching 80 million total registered users.

“They [OKRs] allow you to focus and get aligned and committed around a few things that really matter,” Doerr explains. “And then you can track those and build a culture of risk taking, where it’s okay to fail and you can ‘stretch,’ which is what we like to say. Focus, alignment, commitment, tracking and stretching — that’s the payoff.”

While it’s unclear whether Theranos deployed OKRs, it’s fair to say the startup stretched itself far beyond its actual capabilities and failed to meet its promises to partners and investors. Indeed, although many tech startups come and go, perhaps none have flamed out so spectacularly as Holmes’s company. When the Stanford University dropout founded the company in 2003, she offered the world a tantalizing vision, one where Theranos’s technology could run over 200 diagnostic tests off a single drop of blood at a fraction of the price in a fraction of the time of traditional blood tests.

But the vision far outstripped reality. Theranos raised $700 million from investors by allegedly making false and exaggerated claims about its technology and performance, and last Friday, Holmes and Balwani were indicted as a result on two counts of conspiracy to commit wire fraud and nine counts of wire fraud — charges that stemmed from allegations that the two Theranos executives schemed to defraud investors, doctors and patients.

“[They] picked the wrong objectives,” contended Doerr, who added that implementing and executing on OKRs could have helped the company.

While Theranos’s problems and missteps were numerous, to say the least, Doerr might be onto something. Had Theranos, for instance, established more realistic quarterly goals and ways of reaching those goals, it might have avoided some of the mistakes that ultimately contributed to its downfall.

In hindsight, Theranos clearly needed more time to make its blood testing equipment effective. A more realistic timeline to make its equipment primetime-ready could have helped the company develop equipment more capable of accomplishing what Holmes initially promised. Instead, the company, among other things, found itself voiding two years of tests and sending tens-of-thousands of revised tests results to doctors back in 2016. In other words, thousands of patients received inaccurate results and were likely given the wrong treatments. That was perhaps Theranos’s most egregious transgression of all.

As criminal charges now loom over Holmes and Balwani, it’s too late for Theranos to rectify its myriad mistakes. But the startup’s best-served purpose now may be that of Silicon Valley cautionary tale about how one startup’s bold ambitions were foiled by faulty, corrupt execution.

—

JP Mangalindan is the Chief Tech Correspondent for Yahoo Finance covering the intersection of tech and business. Email story tips and musings to [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

More from JP

Here’s how much Netflix is spending to beef up its original content catalog

Facebook investors grill Zuckerberg: ‘Emulate George Washington, not Vladimir Putin’

Amazon Go chief: We got rid of a ‘not great’ thing about physical retail

How Facebook is ‘getting ahead of the curve’ with new Blockchain unit