Wage gap between top employees and everyone else is 'off the chart'

Income inequality is becoming a dominant topic of conversation, particularly as the 2020 presidential race heats up. Democratic candidates such as Kamala Harris, Cory Booker, and Elizabeth Warren have made it one of their core platforms.

And according to a new study from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), the wage gap between high-income earners and the rest of America might be worse than many realized. The study looked at hourly wages for all workers 16 years of age and older.

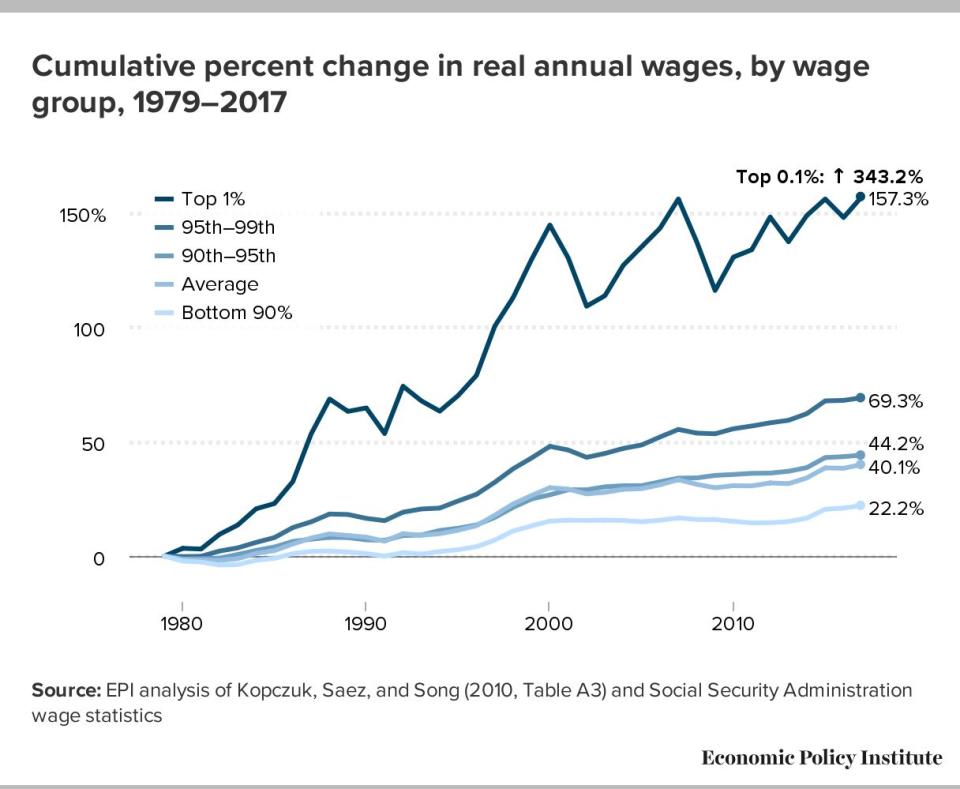

Elise Gould, a senior economist for EPI, noted to Yahoo Finance that the increase is “off the chart — when you look at that particular figure, you see the top 0.1% rises [343.2%] and that’s not even shown on the chart. Because you wouldn’t be able to see any of the other lines.”

Labor productivity has risen by 75% since 1973, yet wage growth has not met that rate. So where did this “excess” productivity go? According to EPI, “a significant portion of it went to higher corporate profits and increased income accruing to capital and business owners. But much of it went to those at the very top of the wage distribution.”

‘You’re seeing a disconnect’

Between 1979 and 2017, the annual wages of the top 1% shot up 157.3%, which was almost four times faster than average wage growth of 40.1%. And, according to EPI, “over the same period, top 0.1% earnings grew 343.2%, with the latest spike reflecting the sharp increase in executive compensation.”

“You’re seeing a disconnect between economic growth and growth in wages for typical workers,” Gould said. The fact that the high-wage earners are pulling further away from the others is “indicative of the growing inequality that we’re seeing in this country over the last four decades.”

She continued: “That means that growth is going to corporate profit. It’s going towards wage earnings at the top … the owners.”

‘The growing inequality that we’re seeing in this country’

Between 1980 and 2016, the U.S. was ranked fourth in the world among countries that saw the biggest wealth increases in the top 0.1%. The only countries ranked higher were China, India, and Russia.

The fact that the high-wage earners in the U.S. are pulling further away from the others is “indicative of the growing inequality that we’re seeing in this country over the last four decades,” Gould said. “What’s happened over the last 40 years is we’ve seen intentional policy decisions that have given more power and leverage to those who have more, versus those who are typical American families.”

These decisions, she said, include new tax policies, weakened labor standards, right-to-work laws, and trade deals that lack protections for working people.

Right-to-work laws were established so “that no person can be compelled, as a condition of employment, to join or not to join, nor to pay dues to a labor union,” according to the National Right to Work Foundation. There are currently 27 states with these laws. However, unions like the AFL-CIO argue that these laws make it harder for employees to collectively bargain for better wages, benefits, and working conditions.

“We’ve seen things like the decline in unionization, which again has been because of intentional policy decisions or actions by employers to make it harder to workers to form unions,” Gould said. “And that has meant there’s been more inequality that’s associated with a growing concentration of wages and incomes at the top.”

‘Reaping the rewards of a growing economy’

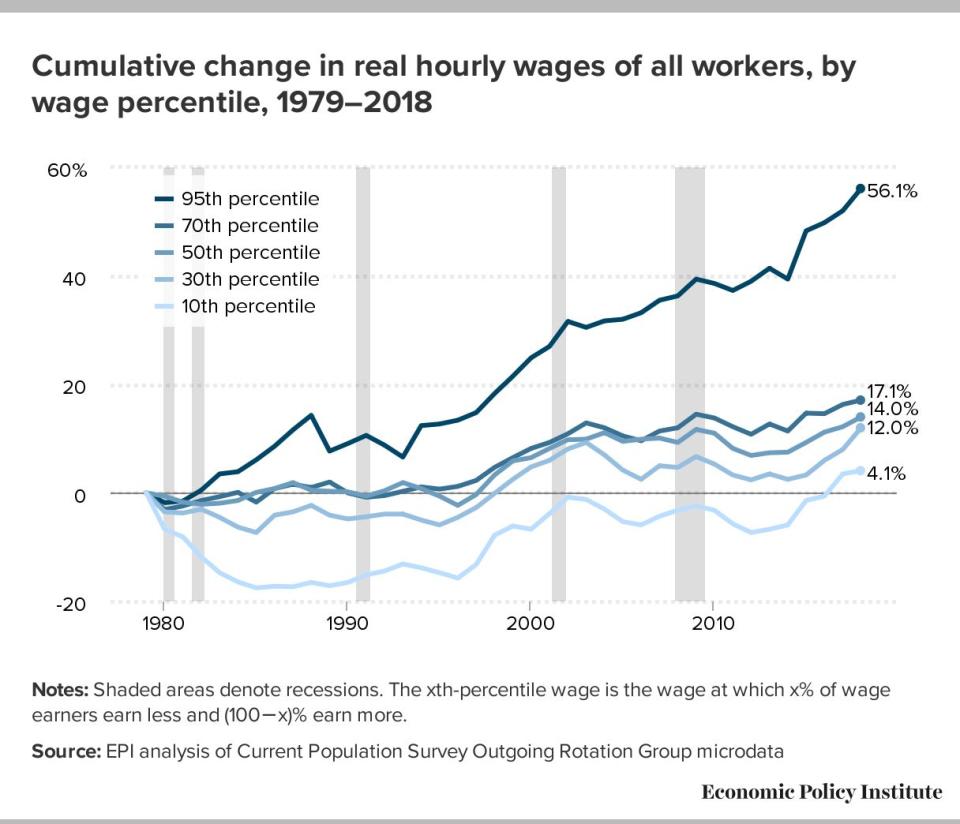

Contributing to the issue is that all wage growth isn’t created equal. As the chart above indicates, hourly wage growth has been relatively stagnant for most workers when compared with the highest earners.

The federal minimum wage has been $7.25 an hour since July 2009. Over the last 30 years, the median hourly wage increased by 14%. Workers in the 10th percentile saw a median hourly increase of 4.1%, yet those in the 95th percentile saw their wages go up by 56.1% during that same span.

Gould doesn’t see policies enacted any time soon to change this current trend.

However, “one of the things that I’m optimistic about is as the economy get closer to full employment and as it gets tighter,” she said, “employers begin to see they didn’t have to pay more to attract and retain the workers they want, because workers become more scarce.”

Ideally, according to Gould, that would translate into a situation where “a greater share of the population was working and they were reaping the rewards of a growing economy.”

She added that it’s possible to get there, “but it’s going to take a lot to reverse the growing inequality that we’ve seen over the last 40 years.”

Adriana is an associate editor for Yahoo Finance. Follow her on Twitter @adrianambells.

READ MORE:

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.