Warren Buffett: Influencers with Andy Serwer [Transcript]

Ahead of the Berkshire Hathaway Annual Shareholders Meeting on Saturday, May 2, 2020, legendary investor and Berkshire Hathaway (BRK-A, BRK-B) CEO Warren Buffett sat down with Yahoo Finance editor-in-chief Andy Serwer at Berkshire’s headquarters in Omaha, Nebraska, for an episode of Influencers.

The conversation was taped on March 10. Below is an edited transcript:

ANDY SERWER: Hello, everyone. I'm Andy Serwer, and welcome to Influencers. And welcome to our very special guest, Warren Buffett, chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway. Warren, nice to see you.

WARREN BUFFETT: Good to see you.

ANDY SERWER: So it's March 10th, and it's the day after the stock market crash. The Dow is down over 2,000 points. Oil cratered to $30 a barrel or so. The 10-year bond went to below 0.5%. What the heck is going on, Warren Buffett?

WARREN BUFFETT: I told you many years ago, if you stick around long enough, you'll see everything in markets. And it may have taken me to 89 years of age to throw this one into the experience, but, you know, the markets, if you have to be open second by second, they react to news in a big-time way. I mean, it's not like the market for real estate, or farms, or things of that sort.

ANDY SERWER: Does this remind you of any other time?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, I've certainly been [around] a fair number of times when panic has reigned in Wall Street. October 1987, and the period around it. I mean, there was panic. At the close of business on Monday, October 19th, most of the specialist firms, which were important in those days on the New York Stock Exchange, were broke. And the next morning there was a check due to the clearinghouse in Chicago that didn't get there. And some time late in the morning, you know, a decision, I think they had made the decision, you know, we're going to stay open, but it was really close. That was-- and, of course, the financial panic. There were-- you had 35 million people on September 1st that weren't worried at all about their money-market accounts. On September 15th, or 16th, they were all panicked.

...

ANDY SERWER: How concerned are you about the coronavirus situation, Warren?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, you've got to defer to the doctors on that, but you know, you get into all of these figures about how flu regularly kills 20 times as many people in this country as-- or 40 times maybe as much as we've seen in the way of deaths, even more than that. But, you know, it is a pandemic. ...

And, you know, Italy's a good example. I mean, it has really spread. So we've got something that we don't know how long it will be with us. We don't know how severe it'll be. But there will be uncertainty about that for a considerable period of time. There has to be.

ANDY SERWER: What precautions are you taking personally? Have you changed any of your habits?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, I'm drinking a little more Coca-Cola, actually. That seems to ward off everything else in life. I mean, I'm 89. I'm in-- I just had two different doctors tell me I'm in much better shape than I was a few years ago. I'm not sure what I'm doing to get in better shape. But by accident, I mean, I had an annual heart check where I wear something around my waist for a couple-- the guys said my-- it's never been better. So I really-- I'm a probabilities guy in my nature. So I, you know, there's going to be 2.8 million deaths this year. And at age 89, [I’m] a little more likely to be that I was in that group. But 2.8 million, you know, what have we had so far? I mean, it will grow. ...

I've always felt a pandemic would happen at some time. I mean, I've actually used that term, I mean, in describing things that can interrupt the progress of, not only this country but the world. It won't stop the progress of the country or the world. I mean, this is a terrible event that's occurring. We don't know how terrible. It may not turn out to be that big a deal when we get through, but it may turn out to be a very big deal, and we just don't know. And I sure don't know, and nobody knows. But there will be other things that happen in the world in the next 5, 10, 20 years. That's the way the world works. It's not a totally even course.

The progress of mankind has been incredible. And that won't stop. I mean, you flew out here yesterday, or today, and you flew over the country that 250 years ago, there wasn't anything here. That's only three of my lifetimes, and there wasn't anything here. And now you've got all these beautiful farms. And you got 260 billion vehicles in the country. And you've got 80 million owner occupied homes. And you've got 155 million, or whatever it is, million people working. And I mean, it's incredible. When I had a medical check the other day, I went to incredible medical facilities that are just two or three minutes from here. And that wasn't here even 100 years ago. And so we keep making progress.

[Read also: Warren Buffett: 'The progress of mankind has been incredible']

We haven't we haven't forgotten how to make progress in this country. And we haven't lost interest in making progress. And that will benefit to varying degrees of all kinds of people, I think, around the world, but there will be interruptions. And I don't know when they will occur. And I don't know how deep they will occur. I do know they will occur from time to time, but I also know that we'll come out better on the other end.

ANDY SERWER: What about the banks? And, you know, boy, they have been awfully hard, because of rates, and the exposure to the energy sector, right?

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah. And you don't know what other exposure there is. I mean, the credit standards have been pretty darn good. And the quality of what's on the books has been terrific. And the liquidity, and all of that, the banks are in a whole different situation than they were ... 10 or 11 years ago. But you don't know-- you don't know the nominals that topple when airlines get bad, and then that affects-- you know, that affects energy demand. They're using less fuel than they were three weeks ago. So there's ripple effects. And there always will be in recessions. That's the nature of recessions as you get ripple effects.

We get ripple effects on the railroad, but there's just less inter-modal traffic moving now because of the supply-chain interruptions and all that sort of thing. But that's-- you looked at-- again, I mean, you know, in 1942 when I bought my first stock, the Philippines were about to fall. I mean, and the day I bought it, the Dow literally was down 2%. And 2%, that was only 2 points, literally. It broke 100 on the downside. But 2%, I felt it. I mean, I went to school in the morning, and I bought these three shares, and when I came home at night, I already had a loss in them.

ANDY SERWER: Yeah, well, I'm glad you kept with it, because other people might have gotten discouraged.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah, but I mean, all the other kids in the 7th grade had their money in something else.

[Read also: Warren Buffett on negative rates and 'the most important question in the world']

ANDY SERWER: Right. Getting back to banks-- just one second, Warren.

WARREN BUFFETT: Sure.

ANDY SERWER: And a specific name, which is Wells--

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah.

ANDY SERWER: Are you getting frustrated with Wells Fargo?

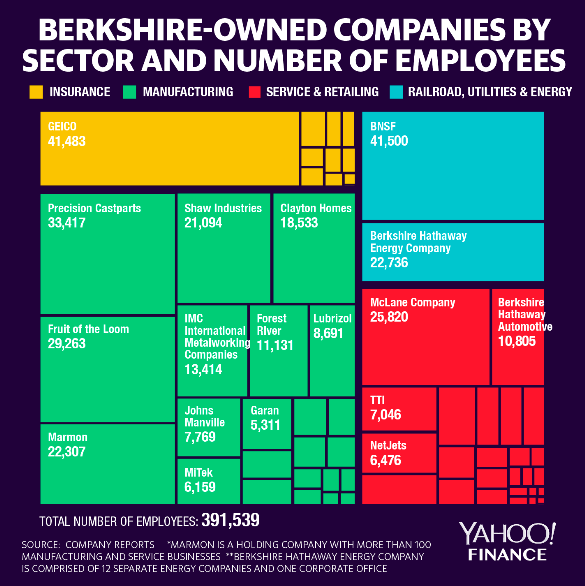

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, I think they've been through a lot of problems, but I don't think that the fundamental franchise and all of that, I'm fine with that. I forget whether it's one out of every three households in the country, and I mean-- mortgage service-- it went through something that various other companies, Geico in the early '70s got-- had its troubles, American Express in 1964 when we got into it, had the salad-oil scandal, which everybody's forgotten about, but it was a terrifying event then. So we at Berkshire-- something will happen. You can't run a place with 395,000 people and not know that something is happening all the time. And you just hope you catch it fast. And the moral of the Wells Fargo story is when you care about something, you've got to act fast And you can have incentives out there that are incentivizing the wrong thing.

And we've had them, everybody's had them. I mean, anybody that has a sales force makes mistakes sometimes in what they incentivize. And bad practices will spread if not jumped on. And that's what you saw at Wells. They didn't-- I don't see how in the world they made any money out of the phony accounts, but, you know, the cost, again, there's a ripple effect. I mean, when something goes wrong at Berkshire, if it doesn't get corrected, there'll be more problems subsequently-- What happened at Solomon, Charlie and I said, you know, get it right, get it fast, get it out, get it over. And any time you see a problem, and you're a responsible party in corporate America, that means just get it right, get it fast, get it out, get it over, and don't skip-- And just put that right in front of you, and go to work on it.

ANDY SERWER: Yeah. Maybe-- I don't know about the get-it-over part with Wells. I mean, it just--

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, if you get-- if you get it right, and get it faster, and get it out, you will get it over.

ANDY SERWER: Right. OK. Got it.

WARREN BUFFETT: And the other things you got, you'll never get to get it over.

ANDY SERWER: Let's switch over to talk about oil. You are an investor in the sector through this Occidental Petroleum deal from last year. You put in $10 billion, I think.

WARREN BUFFETT: Exactly.

ANDY SERWER: And maybe some more after that. I know you get preferred dividends. But that investment has to be underwater at this point. And what's your thinking?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, the $10 billion is a preferred stock with warrants and there is no market in it. I mean, it's a private deal, but we also have about 2% of the common stock. And that's down significantly. And as they said when I did it, I've been-- the biggest variable is the price of oil and I don't know the price of oil. And every day it gets quoted.

[Read also: Warren Buffett's 25 best quotes of all time]

But there's still-- if you have an opinion on oil, you can buy or sell oil either one year out, or two years out, or three years out, or something of the sort. And when oil was in the 30s, there's a lot of agony in the oil patch. And the math just changes terrifically. I mean, it just doesn't pay to drill in a lot of areas. And the Saudis can turn out a lot of it, but with practically no operating costs. I mean, they've got very, very, very cheap operations.

ANDY SERWER: I mean, between that war between the Saudis and the Russians, and then also perhaps the secular decline of demand given concerns about climate change, is this really a great place to invest?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, I don't think the secular demand will change that much, but certainly the immediate demand has changed. I mean, the airlines need less, and people drive less if they're working out of their homes, and you can change-- when you're talking about something close to 100 million barrels a day, if you change it by 5%, that is huge.

ANDY SERWER: I was reading in your annual letter, on the other hand, that you're so proud of Berkshire Hathaway Energy, which is so big in wind power, and has this whole different business model. So you think that alternatives actually have a real future?

[Read also: 5 great quotes from Warren Buffett's latest annual letter]

WARREN BUFFETT: Oh, alternatives have the future in that, and they are the future over time. But you can't change the world, the base of the world. I mean, you've got 260 million vehicles on the road, or whatever number it is in the United States, and I don't know how many around the world, and they're not changing what they use tomorrow. You know, the average age of the American auto I think is 11 to 12 years, something like that. And so the world can't change dramatically. And if anybody thinks you can change energy sources 10% in a year, it just doesn't work that way. But the world is going in the right direction in terms of working toward minimization of carbon.

ANDY SERWER: Speaking of those cars, I mean, look at Tesla and what Elon Musk is doing. I mean, that kind of, is a revolution, right?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, it's an important change. But if you guessed on the penetration of electric cars, let's say we say-- so 17 million, or something, a year, in 2030 when I'll be 100, and I would say that I'd be surprised if more than 1/3 of those would be electric. Alone, that's 2/3 of them are. Plus all the ones in-- so of the total car-- of the total vehicles on the road, it still might be 10% to electric, tops, or something like that, worldwide. I mean, you can't change this mass of transportation. You can't change it in a year or two. It is changing, and it should change. But in terms of just the math of replacing-- if we said we're going to junk all the cars we have, the economy would stop-- I mean, we can't produce-- we couldn't replace them.

ANDY SERWER: What do you think of Elon Musk though ... ? And would you invest in Tesla?

[LAUGHTER]

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, I think you're trying to bait me a little bit.

ANDY SERWER: I don't know. I'm just asking you. You can say ‘no, no, and no.’ Or, ‘yes, yes, and yes.’

WARREN BUFFETT: I'm going to say he does remarkable things.

ANDY SERWER: OK.

WARREN BUFFETT: He's done some remarkable things.

ANDY SERWER: Have you met him?

WARREN BUFFETT: Oh, yeah. He joined the Giving Pledge some years ago. I've only met him once or twice, but yeah, I've talked with him, but not for quite a while.

ANDY SERWER: And would you invest in Tesla?

WARREN BUFFETT: No.

ANDY SERWER: OK. Let's switch over and talk about bond yields and interest rates, because that's a crazy subject right now.

WARREN BUFFETT: It is a crazy subject. It is really crazy.

ANDY SERWER: So what is your thinking on it?

WARREN BUFFETT: I don't know. I have never been able to predict interest rates. I've never tried. I don't-- Charlie and I, we believe in trying to function on what-- focus on what's knowable, and important. Now, interest rates are important, but we don't think they're knowable. And there are some things that are-- you know, this gets back to something-- what was it? Don Rumsfeld, or something.

ANDY SERWER: The known knowns and unknown unknowns.

WARREN BUFFETT: The question is, is the box that says ‘the knowns’ an important, knowable, an important, is there anything in that box? And can you tell what's in that box, and what isn't in that box? And that's what I call knowing your circle of competence. And my circle of competence doesn't include the ability to predict interest rates a day from now, or a year from now, or five years now. So I say, can I function without knowing that? It's the same way as predicting what business is going to do, what the stock market's going to do. I can't do any of those things. But that doesn't mean I can't do well investing over time.

ANDY SERWER: I mean, but things have changed. They're different now, because rates are so low. We have negative rates.

WARREN BUFFETT: It's unbelievable.

ANDY SERWER: And then you were talking about Edgar Lawrence Smith.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah.

ANDY SERWER: And his discovery about bonds versus retained earnings. And then I think you were saying that it makes for, as far as central banks, it makes no sense to lend at 1.4% and then to have 2% inflation.

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, it does make sense for you to buy bonds. If somebody is telling you that they're going to try and destroy the unit in which the bond promise is included, they're going to try to destroy 2% of that a year. And for you to now pay, now receive maybe a half a percent, and pay taxes on it.

ANDY SERWER: Right. I mean, so where do you think these low super rates are going to go, and negative rates? I mean, just what are the implications on--

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, I would say that's the most important question in the world. And I don't know the answer. ... If we knew the answer, it wouldn't be the most important question.

ANDY SERWER: Ooh, I like that.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah.

ANDY SERWER: I mean, I don't like that, but--

WARREN BUFFETT: No, but it's true.

ANDY SERWER: Yeah, yeah. So let me-- let me ask this way then. Has investing in equities changed given the interest-rate environment? It makes equities look super cheap.

WARREN BUFFETT: No, it reduces the hurdle rate.

ANDY SERWER: Right.

WARREN BUFFETT: That's why-- that's why they like to decrease it, is that it pushes asset values higher, because, obviously, if you promise to pay me something at 3% a year, that would have been a terrible instrument for me to own, you know, almost any time in history. But today, if you're good for it, it's fabulous.

ANDY SERWER: I mean, do negative rates scare you, Warren?

WARREN BUFFETT: They puzzle me, but they don't scare me.

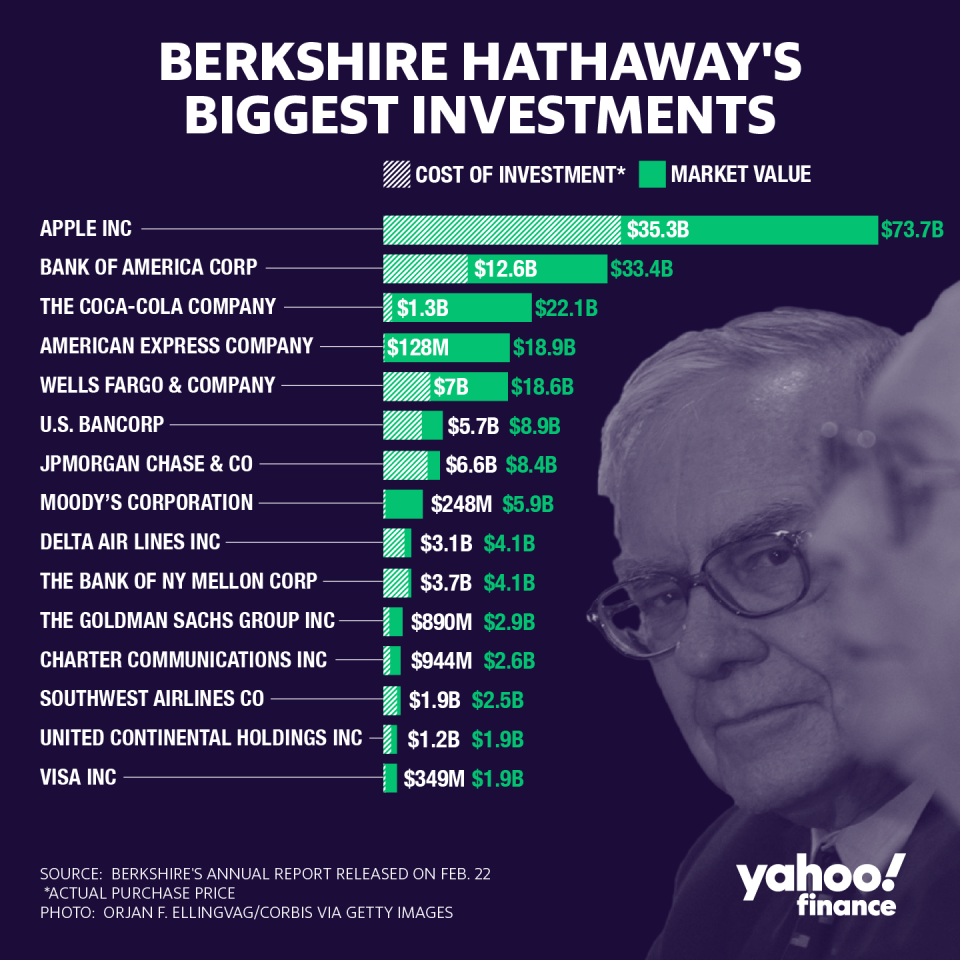

ANDY SERWER: OK. Fair enough. I want to switch over to Apple, one of your biggest holdings. Does the amount of shareholder interest in this company concern you, or Todd, or Ted? In other words, the market capitalization basically relative to the S&P 500. Is that something you look at?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, you look at everything and relate one to another. I mean, that's the nature of markets. So you're always trying to think about, A, what's in my circle of competence, and then what makes the most sense that's within that circle. But the important thing is to know where the perimeter of the circle is. I mean, that's way more important than how big the circle is, or a whole bunch of other factors. So I think Apple is within my circle of competence. I think it's an incredible business run by-- he was one of the great managers of all time, and he was underrated for a while, but now he's being seen for what he really is. It's an astounding-- you can almost-- you know, if we had a--

ANDY SERWER: I got one.

WARREN BUFFETT: If we had a card-table here-- well, yeah, we could put all our products on one table. Can you imagine that? I mean, and I just think of basically the utility of those products to a ecosystem that is demographically terrific and finds that instrument useful in dozens and dozens of times a day. It's almost indispensable, not only to individuals, business, I mean, everything.

ANDY SERWER: And you have one of these babies now, right?

WARREN BUFFETT: I've got-- I've got one of them. I don't have it on me, because I would be afraid it would ring, and I wouldn't know what to do with it.

ANDY SERWER: It's OK. You can take a call during this. We wouldn't have a problem with it. And what sort of apps do you have? Do you have any apps loaded?

[Read also: Warren Buffett's week tracking newspapers, IBM and Apple]

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, they've got a lot of apps on it. But, the other day, actually, yesterday, I was someplace. Normally I don't carry it in town. I carry it out and about. Somehow I was having a little trouble just getting into the-- but this is only me. Any two-year-old could do this, but I was having a little trouble getting to the part where I actually phone somebody. I use it as a phone.

ANDY SERWER: Right. So you're not--

WARREN BUFFETT: But I got a lot of apps on it.

ANDY SERWER: Have you used any of the apps?

WARREN BUFFETT: No.

ANDY SERWER: No gaming apps, or--

WARREN BUFFETT: No, people have shown them to me occasionally. There's even some app with me involved on this newspaper boy tossing thing that it's the app that I revealed a year ago in the movie. I went out to California, and Tim Cook very patiently spent hours trying to move me up to the level of the average two-year-old and didn't quite make it. But I supposedly developed an app in this little movie we had and as I walked out, I turned it to him, and I said, by the way, what is an app? We had a lot of fun. He is a terrific guy.

ANDY SERWER: Right.

WARREN BUFFETT: And that is an unbelievable product.

ANDY SERWER: And just one more about those stocks, you know, the so-called FAANG stocks.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah.

STOP

ANDY SERWER: And, again, you know, does that approach a sort of bubble to you when you just see--

WARREN BUFFETT: No, just the opposite. I mean, you're seeing in this kind of a market, those companies don't need capital. Well, Netflix needs capital. But basically, the big companies in market value don't need capital. And that will separate them even more from the rest of the pack. I mean, they have an incredible business model. If you look at the top 10 market value of companies go back 10 years, 20 years, 30 years. I mean, go back years. It's, you know, it's AT&T, the old AT&T, and General Motors, and Standard Oil, New Jersey, as it was called then.

You know, the 500, you worked on it. But those companies needed money. I mean, when [? Andrew Carnegie went in the steel biz, he built one steel mill, made money on that, saved enough to three or four years later, he built another one. And it was capital retention-- and oil business, the same way. Whatever it was. And now the really incredible companies are the ones that account for just the top five with being well over 10% of the market value of the country. They really don't-- they don't take capital. Their suppliers may in some cases, and all that, but they are really-- overwhelmingly, they're capital light. And that is really different.

ANDY SERWER: Then the question is, why don't you own Google and Amazon, those two in particular? Let's take those two.

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, that's a pretty damn good question. But I don't have a good answer. I definitely should've owned Google. The guys came to see me before they-- when they were--

ANDY SERWER: Larry and Sergey?

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah, yeah. And they-- and we were-- this was a long time ago. I mean, this was before they went public. But they were talking to me a little bit about it. And we were using search at Geico in a significant way. So I knew the power of search. And I actually used search a lot myself, starting with all the- going way back. And search is incredibly valuable to me. And it was valuable to Geico. So I was capable of understanding that. On the other hand, I had seen that Google was taking out all of this, to some degree. And I thought, you know, maybe somebody else can take out Google. And maybe, if they started earlier, somebody else could have taken out Google. So I was always a step behind on that.

ANDY SERWER: What do you? Do you kick yourself? What does Warren Buffett do?

WARREN BUFFETT: No, I don't. I've made so many mistakes, if I tried to kick myself, my legs would be exhausted. You don't kick yourself in the investment-- and you don't kick yourself when you make a mistake. I mean, it is part of what you do. And you know, I was there when Ted Williams batted .406, but that means .594.

ANDY SERWER: Right. And what about Amazon, same kind of thing?

WARREN BUFFETT: Incredible business.

ANDY SERWER: But why-- it's not too late to buy these stocks, is it?

WARREN BUFFETT: I don't know.

ANDY SERWER: But you're not-- you're not buying them right now.

WARREN BUFFETT: No, but I don't buy much. Those are the kind of businesses I think about a lot. Charlie thinks about them a lot. You can't help but do it. I mean, those are incredible business stories.

ANDY SERWER: Right. I mean, so the door is not closed necessarily?

WARREN BUFFETT: No. No.

ANDY SERWER: Right.

WARREN BUFFETT: No, not at all.

ANDY SERWER: OK.

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, actually, one of the other fellows now has bought a little Amazon. I mean, that showed up in our 13F

ANDY SERWER: Ted or Todd.

WARREN BUFFETT: One of the two.

ANDY SERWER: One of the two bought some Amazon, right?

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah. That was in our 13F. Yeah.

ANDY SERWER: Right. There you go. You took the plunge. Berkshire took the plunge.

WARREN BUFFETT: Berkshire took the-- yeah, Berkshire-- they can do anything they want to do. They can't short Berkshire a few stocks.

ANDY SERWER: And then speaking a little bit more about Amazon and Jeff Bezos. He owns the Washington Post.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah.

ANDY SERWER: They offered it to you, my understanding is, when it was for sale. Or, I mean, you talked to Don [Graham] a lot.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah, I talked to Don.

ANDY SERWER: And why-- do you regret not buying it, or did you--

WARREN BUFFETT: No. If I buy anything, it's got to be for Berkshire. You know, I mean, I'm just committed that way. I'm mentally-- Berkshire comes before me. And it would've been a mistake for Berkshire to own the Washington Post.

ANDY SERWER: Because of the political stuff?

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah.

ANDY SERWER: Right, right.

WARREN BUFFETT: People would think-- I will guarantee you that Jeff Bezos is not telling Fred Hiatt, or anybody there, Marty Baron. But I'll bet 80% of the people that are-- some huge number of people just generally think that, if you own a newspaper, you tell them what to run every day. I mean, it's just-- it doesn't happen very often. It used to happen with some papers, obviously. And it probably does still happen with some papers, but that is not the way it generally works, and it certainly wouldn't be the way it would work in the Washington Post.

ANDY SERWER: Yeah, I mean, it sounds like President Trump may think that.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah, well, a lot of-- Kay Graham did not tell Ben Bradlee what to write. I can-- that I know. I mean, and-- but they just don't do it. But I will guarantee you that, you know, particular among political figures, really, the ‘man on the street,’ 90% of them would think that the Graham family was telling editors what to do.

ANDY SERWER: I know you're reluctant to wade into politics.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah.

ANDY SERWER: But I want to ask you--

WARREN BUFFETT: I may demonstrate that reluctance here.

ANDY SERWER: Right. OK. You will in a second, I'm sure. But, you know, we've talked about this before, Warren, that the country seems to be fairly divided up. And you've said it's eventually going to get back together. You still feel that way?

WARREN BUFFETT: Oh, sure, sure.

ANDY SERWER: What will-- how will we get back together?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, you could ask me the same question in the Vietnam period, and I will tell you it was-- it was even more intense. I mean, I watched-- I happened to be in New York at the time, and I watched that crowd come up to Wall Street. I'm just coming up whichever street that is, Broad Street, may have been Wall and Broad, whatever. I have seen in--

ANDY SERWER: Demonstrators.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah. And during the Vietnam period, I mean, people were just as inflamed, I would say, on both sides. I mean, it was-- it was-- and it went on a long time. And you know, it caused the president not to run again in the case of Johnson. So this country has been-- we had a civil war. And so we've had-- we've always had-- we're a democracy. We've got-- we'll have strong opinions on both sides, and sometimes they rub up more than others. But I do not regard this as some unique period in history, although everybody-- I've been reading about unique periods in history ever since I was old enough to read. So--

ANDY SERWER: Some of the things that--

WARREN BUFFETT: My dad-- listen, I grew up in a household that-- that it was a family's belief, and it went beyond my dad, and my mother, but with all my uncles and all-- I mean, basically that the country gone socialist, you know, in the '30s.

ANDY SERWER: Your father was a Republican congressman.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah. Yeah. Very Republican. We didn't get dessert at dinner until we said something nasty about Roosevelt. I mean, my sisters and I you know, we're sort of ritualistic.

ANDY SERWER: Wow. OK. There are calls on the political left and the Democrats to tax billionaires, have a wealth tax, would that stuff be productive, and maybe close the wealth and income gap?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, I think that-- I think I wrote something seven or eight years ago about the fact that there was-- that I was doing a little hyperbole, but there was class warfare, and my class was winning, you know, basically. There's no question that capitalism, as it gets more advanced, will widen the gap between the people that have market skills, whatever that market demands, and others, unless government does something in between, which say, the Earned Income Tax Credit, or all kinds of things. And I think that's a proper function. So I would say that if people-- it isn't some diabolical plot, or anything, but look at it this way, if you go back to 1800, and 80% of the people were farmers, and you were the best farmer in Omaha, and I was the worst, the difference in our value might be two to one. You might be worth twice as much if we're out there picking corn, or whatever we might be doing, or planting.

[Read also: Warren Buffett has two ideas for ending inequality]

But now there's-- we'll say 2 million times-- there's 30 million American males between 20 and 35. And if you're in the top 1/10 of 1% in basketball ability, or football ability, or baseball ability, you aren't worth anything. If you're in the top 100th of 1%, you're getting close. So if the payoff is huge because some guy discovered television many years ago, and another guy discovered pay TV, or cable, and then pay TV, so that your talents-- or Ted Williams got $20,000 a year for batting .406, your talents now, if you make the majors, still doesn't pay well in the minors, but if you finally get to that 100th of 1%, now you're worth millions. And 1/10 of 1%, you can just play Sandlot ball.

So you get this pushing of extreme rewards to people who are very, very good at something the market demands. And people demand entertainment. They demand people apparently that arbitrage securities. I mean, there's all-- there's certain specialties. And that isn't because a bunch of people are sitting in a room deciding we're going to figure out how to take it away from the poor, or anything like that. It's because of the market system, but we want the market system to keep functioning that way, but we don't want people left behind in a society where you've got $60,000 plus of GDP per capita. And that the people on the lower half have been getting-- falling behind the gains overall achieved by the country. And we've-- they aren't worse off than they were 20 years ago. They're somewhat better off.

And they're better off-- they're better off because of things like an iPhone. I mean, that's something that's terribly useful. And everybody-- I get the benefits of search, you know, for nothing, basically. But that's the ultimate tension, is how do you keep a system that produces incredible benefits for everybody, you know? Sports is an easy example, because we all like to watch them. We don't want to watch a bunch of guys like you and me play basketball. So that's where the money is. But that didn't exist 200 years ago.

ANDY SERWER: But then how do we address that?

WARREN BUFFETT: We address it through things like the Earned Income Tax Credit. And we address it so that anybody that worked 40 hours a week, and has a couple of kids, that they don't need a second job in the family. They can have a decent life.

ANDY SERWER: Does that mean increasing the minimum wage?

WARREN BUFFETT: It means increasing the Earned Income Tax Credit, because I think that's a better system. What they need is more money in their pocket. Now, you can do more money in the pocket through a minimum wage, but you don't work- as many people working. You need something so they have money in their pocket. And we can do that, and that does require a-- in my view, it requires higher taxes on people that ... were born into this world with peculiar talents that marvelously now, and 200 years ago, they would have been out there picking corn with me.

ANDY SERWER: Can you take the higher taxes on wealthy people and put it directly to the Earned Income Tax Credit?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, you could.

ANDY SERWER: I mean, because people complain, ‘Oh, my taxes are going-- they're squandered.’

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, nobody likes taxes, obviously.

ANDY SERWER: Yeah. But if you put-- had a program where it was earmarked--

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, that's what people do in their-- when they're on the debate stage, you know, currently it's the Democrats, and they tell you all their new programs, and how they'll pay for it, but they don't tell you how they're going to pay for the ones that are already there. Nobody's discussed the trillion dollar deficit we have. So to talk about how you're going to introduce some new program-- but basically, you don't want to run deficits indefinitely that increase the relationship debt to GDP. There's some point at which that causes real problems, although we haven't seen a lot of places that you might expect to see it.

But this country has the productive capacity to let people like me live extraordinarily well, or sports stars, or entertainment stars, all kinds of-- good managers, whatever-- and still make sure that nobody is really left so that two people have to work, and you have to hold two jobs, and you're wondering how you're going to feed your kids if you're working a-- you know, $7.50 an hour doesn't do it, and $10 an hour doesn't do it, but we can do it. We have the resources to do it.

ANDY SERWER: You said-- shifting gears for a little bit-- you said you might continue to underperform the S&P 500. You might continue.

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, I will from time to time for sure.

ANDY SERWER: But what is the appeal then to own Berkshire Hathaway stock?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, I've got 99% of my money in that, so it appeals to me. But it appeals-- actually, it appeals to a lot of people who feel very comfortable with the fact that we'll never blow it, basically. And I think that they could feel very certain, relative to almost any company, that, you know, we won't be at the bottom quartile, or something of performance, but they can feel very-- they also should feel-- we're not going to be in the top decile either. We run it. We run-- if you're a shareholder at Berkshire, we're running the business like you've got 100% of your money in, and you're going to keep it in. And it's up to us to take care of it.

ANDY SERWER: You said that my market value, my value is not so high. And it seems like you're trying to really create Berkshire Hathaway that works well, maybe not in perpetuity, but for a very long time.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah.

ANDY SERWER: And then you also said we're well prepared for succession. It's almost going to be embarrassing how well. What does that mean?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, it just means that Berkshire doesn't need me. We've got somebody that's extremely better than I am in many, many, many respects to succeed me. And that's-- and you want that in a company. And I want it. I mean, you know, whatever the number may be, but it's many billions that will go for vaccines, or whatever it may be, education, for decades to come. That depends on that. But more important, it's really a couple-- it's at least a million people, where at this proportionate number have got something close to their whole savings in. And so with our partner-- Berkshire came out of a partnership. Charlie ran a partnership; I ran a partnership.

We actually-- we do look at the people's partners. And we look at a partner as somebody who trusts us to make sure that we don't-- they don't get killed in the process. And they are not-- if they're shooting for the top 1% of performance, or 5%, they're not going to find it. They might have found it in our partnership back when I worked with tiny sums of money, but we can't do it, and we don't want to think we can do it.

ANDY SERWER: You said a person to succeed me, I think, just now. And so is that a person that we know? Or is it-- I mean, there are various people at the top of Berkshire that you've tapped. And there's Greg and Ajit are going to be on stage this year at the meeting.

WARREN BUFFETT: It depends what happens to me, and what happens to other people, but--

ANDY SERWER: It's not Justin Bieber, or someone out there.

WARREN BUFFETT: No, it isn't even Elon Musk. See, but the interesting thing is, if you take our top 10 holdings at Berkshire, we've got probably about $150 billion in them. I don't know who the successor is to the CEO in any one of those 10. And I've watched a lot of successors come and go in those holdings. So to think that we wouldn't have somebody able, it's just crazy, I mean, in our case. It's just the ultimate responsibility of the board of directors as to have the right CEO, and be prepared if something happens to that person.

ANDY SERWER: Right.

WARREN BUFFETT: You said that we possess skilled and devoted top managers for whom we're running Berkshire is far more than simply having a high paying or prestigious job. How do you know that?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, you don't know for sure, but you don't make judgments on that, you make judgments on a marriage. I mean, you've got more time to look them over-- in selecting successor CEOs. But that's the most important decision though that you make. It isn't what their IQ is. And it-- it isn't even necessarily the top-- maybe in a given type of managerial skill. I mean, if they're the kind that will leave you tomorrow-- I mean, you really want somebody that is devoted to Berkshire. And incidentally, we look for the same thing in our subsidiaries, and others. We've got a group of managers, and dozens, and dozens, and dozens. Now, everyone doesn't feel this way. I mean, but we've got a much higher percentage that feel that way than-- I think, than virtually anybody else. But you can't bat 1.000 in that game.

ANDY SERWER: Another topic that people are very keen on right now is student debt. And I know that you have really prouded yourself on helping students. Is this something that really concerns you?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, it would be a tough consideration for me if I were going to school, or whether I wanted to, not only invest-- I'm talking about college-- where I wanted to invest the four years. I didn't want to go to college that much when I got out of high school. But not only the four years, but if I had to incur, you know, hundreds of thousands of dollars in student debt, I don't know which decision I would make. Now, higher education is really expensive. And we've helped out many thousands of students. And the Gates Foundation has done the same thing, and many other of the foundations that I support. But it's just expensive. It's very expensive.

ANDY SERWER: Is still worth it?

WARREN BUFFETT: It depends on the individual. It depends on the individual, and the school. I mean, it-- there is a lot to learn in those four years. I mean, there's a lot you can learn in those four years. And whether you do or not depends more on the individual. I don't think-- I don't think it makes sense for everyone to go to college. And I'm not so sure it made sense for me to go to college.

[Read also: Warren Buffett on college: 'I’m not sure it made sense for me’]

ANDY SERWER: Really? Come on.

WARREN BUFFETT: No, I'm not kidding. I don't know. I mean, I learned a lot by reading. And, you know, I spent three or four years-- well, counting graduate school, four years, that I could have been doing other things. There were a lot of intelligent things to do then. Who knows. I don't think it was essential. I mean, I had some wonderful people I met through it. Main thing when I went to Columbia though with taking Ben Graham's course, I already knew what he was going to say. I mean, I read it. I understood. I mean, he was a very good writer. But it was inspirational. It was an inspirational more than it was educational.

ANDY SERWER: We have a few questions from our audience at Yahoo Finance, from Twitter. One is, what advice would you give to a young investor today?

WARREN BUFFETT: Well, you've got to understand accounting. You've got to-- that's got to be like a language to you. And so, yeah, you have to know what you're reading. I mean, unless you know that language-- and some people have more aptitude for that than others. But that's one thing I learned by myself. Now, I took courses afterwards, for example. But I learned it myself, and largely. So you have to do that. And you have to have the attitude that you're buying part of a business, and not that you're buying something that wiggles around on a chart, or that has resistance zones, or 200-day moving averages, or that you buy puts or calls on, or anything like that, you're buying part of a business.

[Read also: Warren Buffett offers his 2 best pieces of advice for aspiring young investors]

And if you buy intelligently into a business, you're going to make money. And then you have to buy something that, in my view, which you'd do if you're buying a business, that you're not going to get a quote on for five years, that they're going to close the stock exchange tomorrow for five years, and that you'll be happy owning it as a business. If you owned Coca-Cola, it didn't make any difference in 1920 when it went public. The important thing was what it was doing with customers. And you probably would have been better off if there wasn't any market in it for 30 or 40 years, because then you wouldn't have gotten tempted to sell it. And you just watch the business, and you'd watch it grow, and you'd feel happy. So the proper attitude toward investing is much more important than any technical skills.

ANDY SERWER: Another question from one of our audience members, with all your success, what keeps you and Charlie going?

WARREN BUFFETT: We have so much fun. I just talked to him the other day for an hour. And we have fun every time we talk. And we are having-- we are doing what we love to do with people we love every day. And, you know, I've been lucky on how-- God knows, you know, how Charlie at 96, and me at 89 with our habits on everything-- it's-- I don't know what it's a testament to. I think, actually, being happy in what you're doing makes a huge difference. And you don't want to go around having grudges against people. I mean, all these things, of course, you think negatively whether it's about the world, or about individuals, or about your own bad luck, or anything of the sort, just forget it, basically. I think that helps.

ANDY SERWER: How do you clear that stuff out of your mind?

WARREN BUFFETT: I don't know whether you're born to some extent that way, but you certainly see that it works. And, you know, I mean, you just take the people you know, and the ones that are sour around the world, the world gets sour on, you know, basically. And so it's-- now, it's got to be tough. You know, and if you've got some major illness, or something of that sort. I mean, that's just you can have terrible luck in life, and it can seem very unfair to you, but you're going to have-- you're going to have a better experience in life if basically you see the positive side in things. People will see the positive things in you at that point.

And if you can find-- if you can find some-- I'd say, look for the job that you would take if you didn't need a job. And if you can find that where you're actually-- I don't-- I don't think I've had a job. I mean, I've never-- I would define work as doing something when you'd rather be doing something else. And, you know, when I sold shirts at Penney's, and I was getting $0.75 an hour, I would rather have been doing something else. But since I've been certainly 24, I've always-- I've never-- there wasn't anything else I wanted to do. And I had everything I needed. And life was wonderful. And I tell the students that, you know, you've got to live.

So you may take a job at first for some organization that you don't admire, or work for somebody you don't admire. But look for somebody you admire. Look for somebody where you're looking forward to working with them that day, and doing something that you're looking forward to, that you'd do if you didn't need the money. And Charlie and I found that a long time ago.

ANDY SERWER: And you're going to turn 90, what, in a few months?

WARREN BUFFETT: In about five months.

ANDY SERWER: Five months.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yeah, I'll send you a reminder.

ANDY SERWER: I'll send you a present. That's what you're looking for.

WARREN BUFFETT: Then you’ll really get a reminder. You get a second reminder, actually.

ANDY SERWER: So looking back over these years, what are you most proud of?

WARREN BUFFETT: Oh, I would-- well, I'm certainly-- but I have to give all the credit to their mother, but I'm certainly proud of how my children have worked out. I mean, it's not easy, in a sense, having a name that becomes famous, or thought of as having all kinds of money, although they don't. But all three of them are now in their 60s. In fact, you're looking at a guy whose youngest child is 61. I mean, that's-- and they've all-- they've all lived very productive lives and they all get along fine with each other. I've seen a lot of rich families, and it doesn't always work out that way.

ANDY SERWER: And another question from the audience. If you were going to start a business today, what kind of company, or what industry would you look to get into?

WARREN BUFFETT: I'd do the same thing I've done. I mean--

ANDY SERWER: Can everyone do what you do though? I mean, do you think that--

WARREN BUFFETT: I'm cut out for managing money. You know, it doesn't mean that-- you know, different people have different kinds of minds. I play bridge with people who can remember the hand they played 30 years ago, you know, and watch a basketball game at the same time. But so there's all kinds of different smarts that people have. And I've been fortunate enough that I might have been in something that pays off big. And I could be very good at something else that is just as much utility to society, but it doesn't-- it doesn't fit the market system as well.

ANDY SERWER: And then just finally, what celebrities that you've talked to this year--

\WARREN BUFFETT: Oh, you!

ANDY SERWER: Hardly. How do people like Katy Perry or LeBron James get in touch with you?

WARREN BUFFETT: Oh, I'm easy to find. I'm so easy to find. Yeah. And I see all the mail that comes in. I'm not a hard guy to access.

ANDY SERWER: All right. So write him a letter. Are we going to leave it at that? Warren Buffett, chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, thanks so much for your time.

WARREN BUFFETT: It's been fun. Thanks.

ANDY SERWER: I'm Andy Serwer. You've been watching Influencers. We'll see you next time.