Exclusive: Wells Fargo automated high-net-worth wealth management as advisors faced sales pressure

“Established 1852. Re-established 2018 with a recommitment to you.” That’s the tagline from Wells Fargo’s new advertising campaign, which is designed to move the bank past its huge fake-accounts scandal caused by the immense pressure put on its bankers to sell. Indeed, Wells makes a point of saying that product sales goals are gone — for its branch bankers.

But in the upper echelon of a different division of Wells Fargo — its Wealth and Investment Management division — the intense pressure for sales is alive and well, according to hundreds of pages of internal documents reviewed by Yahoo Finance, and interviews with four former employees in that division. In fact, even as Wells was de-emphasizing sales goals within its community bank, the pressure on its wealth managers was being turned up.

Documents show that within the wealth management part of Wells Fargo’s high-net-worth Private Bank, investment management control was transferred from human advisors to formulaic models — a move that does ensure consistency and reduce the risk that an advisor does something crazy, but one that the former advisors felt was also designed to make advisors focus on sales.

“As a company they emphasized sales to such a point that I felt just like the salesmen in ‘Glengarry Glen Ross,’” said one former advisor, referencing the David Mamet play and 1992 film in which salesmen are given a sell-or-be-fired pitch that leads to a break-in and fraud.

Two former advisors also say they felt they were supposed to hide the shift from clients so the services could continue to be represented as highly personalized advice.

“The firm made it very clear that we could not discuss the fact that we were no longer managing the portfolios,” one former advisor told Yahoo Finance. “That remains one of the biggest ongoing secrets kept from wealth management clients to this day.”

Another advisor, who left after he felt his job had completely pivoted to sales, said: “I was going to be a sales person representing that I managed the portfolio. I couldn’t live with that.”

In his almost 20-year tenure with the bank, the advisor said it had gone from “a wealth management platform trying to do the best for clients to ‘protect Wells Fargo, generate more revenue.’”

“At Wells Fargo Wealth Management, our goal is to work closely with clients to provide the right mix of services for their needs, offered by team members dedicated to taking care of clients the right way,” says Wells Fargo spokesman Vince Scanlon. “We embrace a holistic investment objective process as we professionally manage our clients’ wealth. We fully believe in our optimized portfolios approach. These are designed to balance risk and return representing our best thinking to align with the client’s needs and perspectives resulting in customized portfolios tailored for each client. This is one reason clients choose Wells Fargo.”

The “optimized portfolios” refers to the more formulaic shift in management.

In March, Wells Fargo said in a securities filing that its board was conducting an independent investigation of “certain activities,” including “whether there have been inappropriate referrals or recommendations,” within its Wealth and Investment Management business. In June, reports emerged that the bank might be considering restructuring its wealth management business.

The wealth management teams’ job description changes

Wells Fargo’s investment management division includes the 14,000 or so members of Wells Fargo Advisors, who cater to average investors, but it also includes a high-net-worth division of 200 or so highly trained advisors in the Private Bank, who were required to have graduate degrees and designations that showed their investing expertise. In the past, investments were customized, and the sales pressure was minimal.

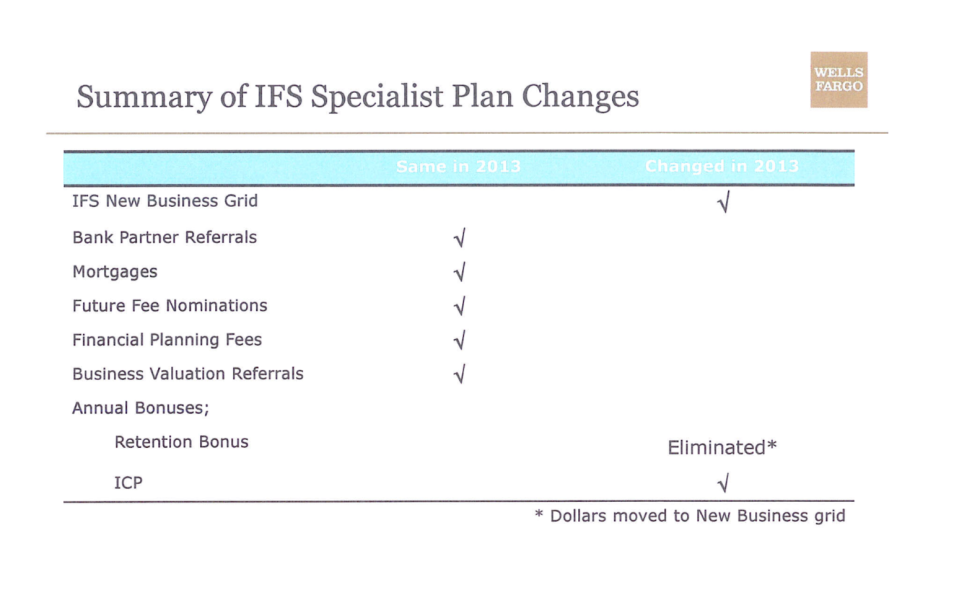

But a series of moves Wells has made in the last five years have changed things for these high-net-worth advisors. In late 2012, according to internal presentation documents, the bank eliminated a retention bonus that rewarded advisors for holding onto existing clients. In its place, advisors received additional compensation for new business. Indeed, one page of a document labeled “2013 compensation plan preview,” which details the changes, shows “Retention Bonus – Eliminated.” An asterisk next to it says, “Dollars moved to New Business grid.”

A more gradual change came in the way in which advisors were ranked. They used to be ranked by investment performance, but that shifted to sales rankings, which were circulated monthly.

In 2014, Wells Fargo began to reduce the amount of truly customized portfolio management that advisors could offer their clients. Investment “managers” — who had been choosing the investments they felt were best suited for their clients — became investment “strategists.” As part of what was called “best practices,” these strategists were supposed to spend their time on “client management,” while the actual investment management was handled by service centers located in Las Vegas, Charlotte and elsewhere, according to a 2014 presentation document from a summit called “IFS Next Paradigm.” (IFS, or Investment and Fiduciary Services, was an older name for the Wealth and Investment Management group.)

The strategist was to “use our guided portfolios (our best advice) as the foundation of portfolio construction” and “customize based on client’s needs,” while service management was to “execute the portfolio.” One document also says the strategist role has “evolved with expanded focus on asset management acumen, sales skills, and leveraging Service Management.”

It sounded harmless enough, but one former advisor says that this was a “pivotal moment.” “They were essentially explaining where you fit into the spectrum,” he says. “Everyone said, ‘Wait, service management is responsible for investment management?’ This is what we’ve spent our lives doing.”

Aside from pressure to climb to the top of rankings, advisors were given a stern warning about the focus on growth in 2015. One internal presentation document called “One Model On Model” exhorts advisors to “have the courage to manage out culture killers who send the wrong message and inhibit long term revenue growth.”

This change at Wells Fargo was reflected in advisors’ schedules, as portfolio management time became sales time. One former advisor estimates that a normal week came to mean about 20% client meetings and 80% sales.

“Sales, sales, sales was hammered home to us daily and with the monthly reminder of where you ranked,” says this former advisor. “It was a terrible situation…because most of our time was spent prospecting for new clients instead of managing assets and it often required a lot more prep time to put together proposals to win the business.”

In documents, Wells Fargo repeatedly used the word “consistent” to describe the reasoning behind the switch to models. One presentation says that “key financial benefits” include “productivity improvements” and “revenue enhancements.” But sales was certainly a component of the change.

A document summarizing a conference held in August 2016 notes that this one was in contrast to past conferences because it “focused almost exclusively on sales and growth.”

At that time, Wells also introduced a specific sales goal in the form of “NCA,” which is shorthand for “new client acquisition;” at the conference, one agenda item was described as “Becoming personally comfortable with NCA.” And there was a goal, which overall was “10% growth over 2015 baseline” with “specific office and region goals.”

Wells Fargo clients got models instead of personalization

In early August 2016, the pressure to follow the models increased. One presentation is described as the “how to guide for building portfolios representing the firm’s best thinking in just a few clicks.” Strategists were allowed to hold some securities in client portfolios outside of the models — but these deviations, called “exceptions,” were tracked and adherence to the model was a factor in your compensation.

There were ways to customize portfolios with private equity offerings and options strategies, among other things. This amounted to nine models, from aggressive growth to income. But the former advisors Yahoo Finance spoke with felt the options were limited. For instance, if you chose to construct a portfolio using stocks, rather than mutual funds, there was a growth or a value option. You could supposedly customize either one — but according to a presentation, the customization was limited to restricting — or buying — certain stocks a client wanted to avoid or own, and making sure capital gains didn’t go above a certain amount the client specified.

“They put everyone in a model so you didn’t have to use your brain to figure out any stocks,” one former advisor said. “So you would use the brain to explain to clients why it was in the model.”

In presentations, Wells described the move to models as a way to reduce risk, in part for regulatory reasons, and ensure consistency. But the former advisors Yahoo Finance spoke with felt it stripped clients of flexibility and could impact portfolios negatively.

“If you brought [a client’s existing] stocks onto the platform, you had a year to get rid of, 80, 90 stocks. That created tax liability and destroyed wealth,” one advisor said.

Keeping the stocks that were not in line with the model meant an advisor having a lot of “exceptions,” which an internal document notes was required to be below a certain range for “performance evaluation purposes.”

This also could put pressure on advisors to make decisions that weren’t right from an investment perspective. “How do you explain to a client, ‘I [adjusted the portfolio] because if I don’t do this this year, I don’t get my bonus?” he said. “It’s hard to have meaningful performance when taking capital gains all the time.”

Another advisor said it was even a problem if a client wanted to buy a company’s stock that wasn’t in the model, as it counted toward his list of “exceptions.”

“Strategists offer advice to clients and they work closely together to design their portfolios,” says Wells Fargo’s Scanlon. “However, if a strategist’s actions seem to add more risk to a portfolio than a client agreed to, we have a fiduciary responsibility to find out why. Policy violations can impact bonus compensation.”

Two of the advisors said they felt that they were prohibited from telling clients about the model.

“Never did I tell [clients] they’re in a model,” said one. “The pitch was a customized portfolio tailored to the clients’ needs.”

Another former advisor said he felt similarly restricted.

“We went from being able to offer complete customization in client portfolios to just nine investment objective models,” the former advisor says. “All of this is being actively hidden from clients.”

Wells Fargo categorically disagrees with the former employees’ characterization of its process.

“Client portfolios are not model dependent and any statement to that effect is incorrect. Clients are involved from start to finish when designing their portfolios, from designing the investment strategy to signing off the final approach,” Scanlon says. “Risk management measurement standards to compare asset allocation guidance and client portfolios are in place as part of an effective risk management system that helps ensure clients have commensurate risk/return exposures.”

Not mentioning the model could sometimes put advisors in an awkward position with clients.

“The guys running the model say ‘you’re going to sell something’ and you just told a client you like it,” one advisor recalled.

In April, Jon Weiss, the head of Wells Fargo Wealth and Investment Management, wrote an open letter in which he said that “We at Wells Fargo stand by our approach to client investment advice that is tailored to the individual.”

Not managing money frees up time to sell

As the transition to “guided portfolios” was implemented, time spent managing money went down even further to “virtually nothing,” one former advisor said.

“Our only responsibility was to assign clients to a model and then approve the model team requests for a sign-off on the slight changes they would make to the account,” the advisor said.

“The challenge or breakdown was the emphasis was on getting more clients, not on taking care of current clients,” says another. “Once you became a client, there was a fair amount of auto pilot.”

A series of emails from early 2017 shared with Yahoo Finance shows a strategist being asked to sign off on changes to an account that were “cleaning [it] up to the value model” per instructions from an employee in a service center.

Meanwhile, the sales pressure took a different form. In an internal document reviewed by Yahoo Finance, NCA, or new client acquisition, was listed as a “Critical Business Metric” in performance reviews in 2016, but then, in 2017, it was excluded from the criteria for investment strategists getting their bonuses.

But even as NCA was downplayed, another target was instituted. In October 2016, around a month after the fake accounts scandal broke and Wells Fargo loudly discontinued sales goals in its retail bank, Wells Fargo introduced a new compensation plan in its wealth management division. The plan included “new revenue generation expectations,” according to an October 18, 2016 presentation given with the call. When the comp plan was rolled out, one advisor took notes. According to these notes, Erik Davidson, the chief investment officer for Wells Fargo’s Private Bank, said, “We are changing everything to be more sales focused.”

In essence, the new plan required at least some advisors in the Private Bank to bring in new revenue to Wells Fargo. The requirements differed, but one class of advisors had to bring in new revenue to Wells Fargo (calculated on a rolling 12-month look back) of $225,000. That required around $22.5 million in total sales, since fees were around 1%. Advisors who didn’t meet the goal would face a 25% cut to their compensation.

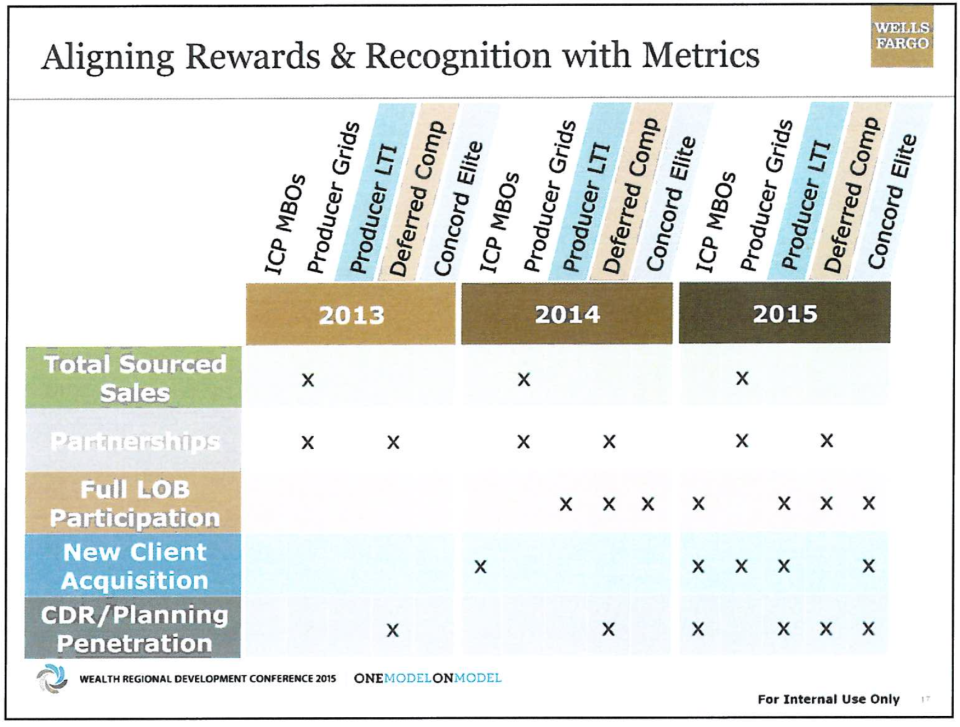

Meanwhile, employees who topped the sales rankings were treated to all-expense-paid “Concord Elite” trips to resort locations, according to one source. (The name is from the maker of the early stagecoaches.)

Incentives like all-expense-paid luxury trips have been frowned upon by consumer advocates. A 2017 report from Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s (D-MA) office on conflicts of interest in financial advice noted that “providing sales incentives such as luxury cruises and all-expense-paid trips to tropical resorts” could “cause advisers to put their own interests ahead of their clients’.”

Clients start getting upset as the model breaks down

Even as the move to models was being implemented fully, the models were underperforming. In 2016, the models underperformed their benchmarks significantly. According to the internal documents, the large-cap growth portfolio performance was up 0.03% gross of fees, compared to 7.08% in the Russell Growth 1000, its benchmark. Net of fees, the year finished in the red at -0.47%.

Even worse, most clients would compare these results to the S&P 500, which was up 11.96%, one former advisor told Yahoo Finance.

The value portfolio model, another option besides growth, was worse, so bad in fact, that many advisors used the growth model instead. At the end of the first half of 2016 the model was down -4% for the trailing year as the S&P 500 had surged 4%.

Annual numbers shouldn’t necessarily be an issue to anyone who cares about long-term performance. But two of the advisors Yahoo Finance spoke with felt it put them in an awkward position, because when clients complained, advisors were pressured not to reveal the bank’s process of how investments were really managed.

One former advisor explained the doublespeak he heard after getting too close to the truth with a client. His boss, he recalled, told him he was not being asked to lie — but also said that he was not allowed to reveal the full details of the investment process.

Last week, on Wells Fargo’s conference call announcing second quarter results, CEO Tim Sloan reiterated that whatever the problems in wealth management, the bank’s advisors are focused on doing the right thing for clients. “It’s whatever makes the most sense for that customer,” he said.

Read more:

Wells Fargo’s scandals just won’t die

Bethany McLean is a contributing editor at Vanity Fair and bestselling author. Her latest book,” Saudi America: The Truth About Fracking and How It’s Changing the World,” is coming out in September 2018.

Ethan Wolff-Mann is a senior writer at Yahoo Finance focusing on consumer issues, tech, and personal finance. Follow him on Twitter @ewolffmann.