Why federal student loans need new protections on debt collection

Democrats have roundly criticized President Trump for making aggressive use of his executive authority and to be sure, the President has repeatedly tested the limits of his constitutional powers. Yet in one area, they are one-upping the President, pressing Joe Biden, if elected, to cancel up to $50,000 of federal student loan debt for millions of borrowers.

Across-the-board debt cancellation would be a highly aggressive use of Presidential power under the Higher Education Act where the authority to “waive, or release” debt appears to be focused on troubled borrowers. But given the drag of $1.5 trillion of federal student debt on our economy, this may well be justified. At the very least, this executive authority should be used to give relief to deeply distressed borrowers, better conforming government debt practices to those of regulated bank lenders.

When making unsecured consumer loans, banks are required to evaluate whether a borrower will be able to make principal and interest payments on their loan once it becomes due, and also make standardized disclosures about loan costs and repayment terms. If a loan becomes delinquent, government supervisors generally require banks to write the loans off once they are 120 days past due. While banks can continue to seek recoveries once the debt is written off, such collection efforts are subject to state statutes of limitations (SOL) and as well as the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act. National lenders frequently default to the most conservative state SOL and stop collection efforts after three years. Private lenders are also subject to various state and federal limitations on “negative amortization” — that is, the practice of adding unpaid fees and interest payments to amounts owed. This can lead to distressed borrowers’ having debt obligations that grow by multiples of the amount they originally borrowed and is frowned upon by bank examiners.

In contrast, the government makes no effort to determine whether student loans are affordable, nor do borrowers receive standardized disclosures of loan terms and estimated loan repayments. In addition, government accounting does not require write-off of seriously delinquent student loans. This is perhaps because there is no federal statute of limitations on student loan collections and the government can resort to collection tactics not permitted in the private sector, including garnishment of Social Security and other government benefits. Consumer protections against abusive debt collection tactics do not apply to the government, nor do state statutes of limitations. The government regularly garnishes the wages of defaulting borrowers charging a whopping 20% per payment. It also utilizes repayment plans that set minimum payments below that required to cover interest, substantially adding to a borrowers total obligations over time because of negative amortization. In some cases, the government even charges interest on a borrower’s unpaid interest. Finally, student debt is generally not dischargeable in bankruptcy, meaning that the government can and does follow a defaulting borrower to their death bed.

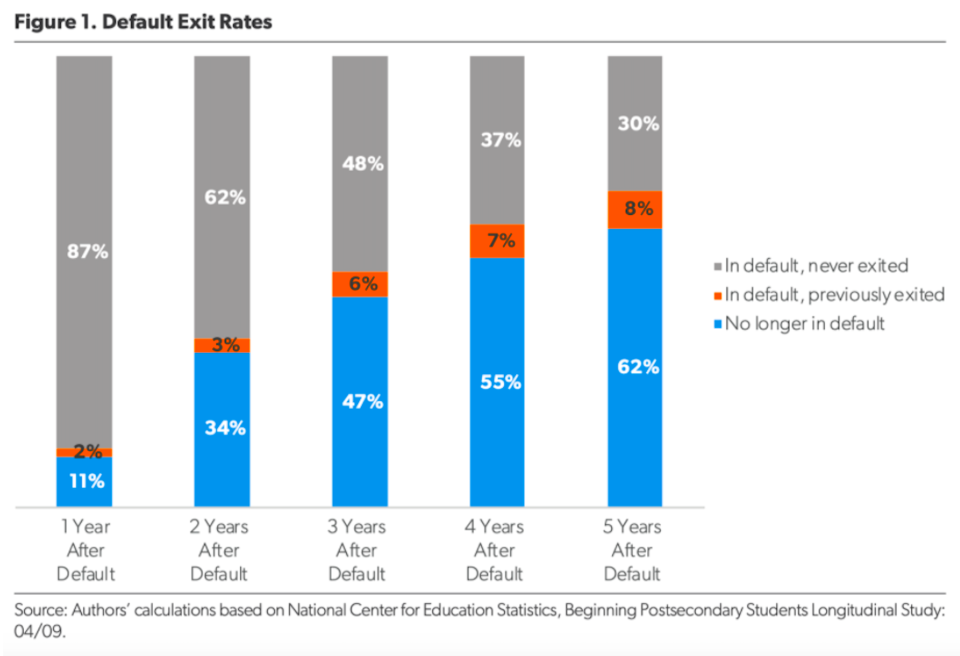

To better align the federal government practice with that of private lenders, there should be a time limit on debt collections for student borrowers in default. Three years would be consistent with the most conservative state SOL. At most, the limit should be five years. Research shows collection efforts after this point are unlikely to be successful, costing taxpayers needless administrative expense and creating stress for borrowers.

To address the pernicious impact of negative amortization, a student borrower’s total repayment obligation (including fees) should be capped at some reasonable multiple of the amount they originally borrowed, perhaps 1.5x for undergraduates, with higher multiples for graduate and professional school students who borrow more but also have higher incomes. Cancelling the debt of those in default for longer than 3 to 5 years, as well as debt that exceeds 1.5 times the amount originally borrowed would eliminate the worst of the government’s debt collection abuses.

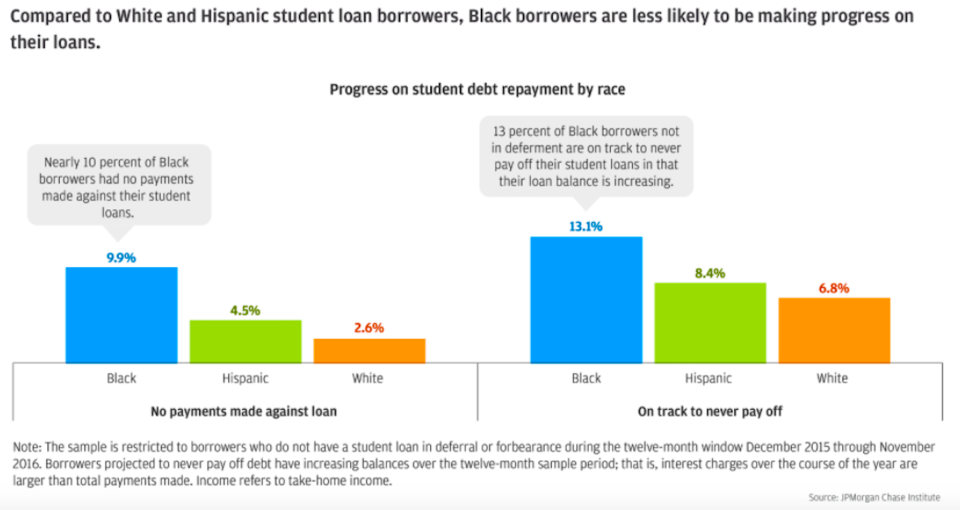

Such steps would be particularly beneficial to low-income borrowers of color, including African American borrowers. Research shows that Black borrowers are overrepresented among borrowers in multi-year default, and also are more likely to have mounting loans balances because of negative amortization. Those unable to finish their education end up with high debt and no degree.

Black borrowers are also more likely to have been targeted by a for-profit college diploma mill. And they are hit the hardest during major economic crises, including this pandemic.

Bank examiners have a name for banks that try to put distressed borrowers in “repayment” plans hoping that someday they will be able to repay their debt obligations: “extend and pretend.”

Not only does such a practice obscure a bank’s true financial strength, it is bad for the economy. Banks nurse balance sheets ladened with uncollectible debt obligations, instead of writing off the losses and moving on. Most importantly, the debt overhang caused by extend and pretend inhibits consumer spending, as borrowers are never quite freed of their past obligations. The ability to secure a fresh start is why we have a consumer bankruptcy process, but this process is denied to student borrowers.

During the Great Financial Crisis, resistance to cancelling government-backed mortgage debt – also non-dischargeable in bankruptcy- placed a prolonged drag on our economy. With the government’s stubborn unwillingness to cancel the student debt of even the most distressed borrowers, we are repeating that same mistake. Much more needs to be done to reform the student loan system. I have long argued that the government should scrap debt in favor of Income Share Agreements. But at a minimum, we should hold the government to the same standards it expects of private lenders.

We do not allow banks to extend and pretend loan obligations that are clearly unaffordable to the borrowers. We should at least ask the same of our government.

-

Sheila Bair is the former Chair of the FDIC and has held senior appointments in both Republican and Democrat Administrations. She currently serves as a board member or advisor to several companies and is a founding board member of the Volcker Alliance, a nonprofit established to rebuild trust in government.

Read more:

The danger of allowing banks to artificially boost capital ratios

Low interest rates widen the gap between Main Street and Wall Street

Why student loan forgiveness should target graduates who need it the most

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.