Why the 2010s were a decade divided

It had been a long, heated day of politicking for Illinois Republicans inside the state capitol building in Springfield, but finally a consensus was reached. That evening, on June 16, 1858, at 8 p.m., the gangly figure of 49-year-old Abraham Lincoln strode to the podium to accept his party’s nomination for U.S. Senate. He began his speech with a few sentences of preamble and then uttered the words now familiar to millions of Americans:

“A house divided against itself, cannot stand,” Lincoln said. And then he continued, explaining that the country could not be half slave, half free. “I do not expect the house to fall,” he said, “but I do expect it will cease to be divided."

Lincoln didn’t coin the phrase “house divided.” That goes back to at least the Gospel of Mark 3:25, but Lincoln’s speech, with its ringing, unequivocal language, thrust him onto the national stage. While he lost the election to Democrat Stephen Douglas, Lincoln was elected president two years later. And his house divided metaphor was etched into American history.

An apt metaphor for the past decade

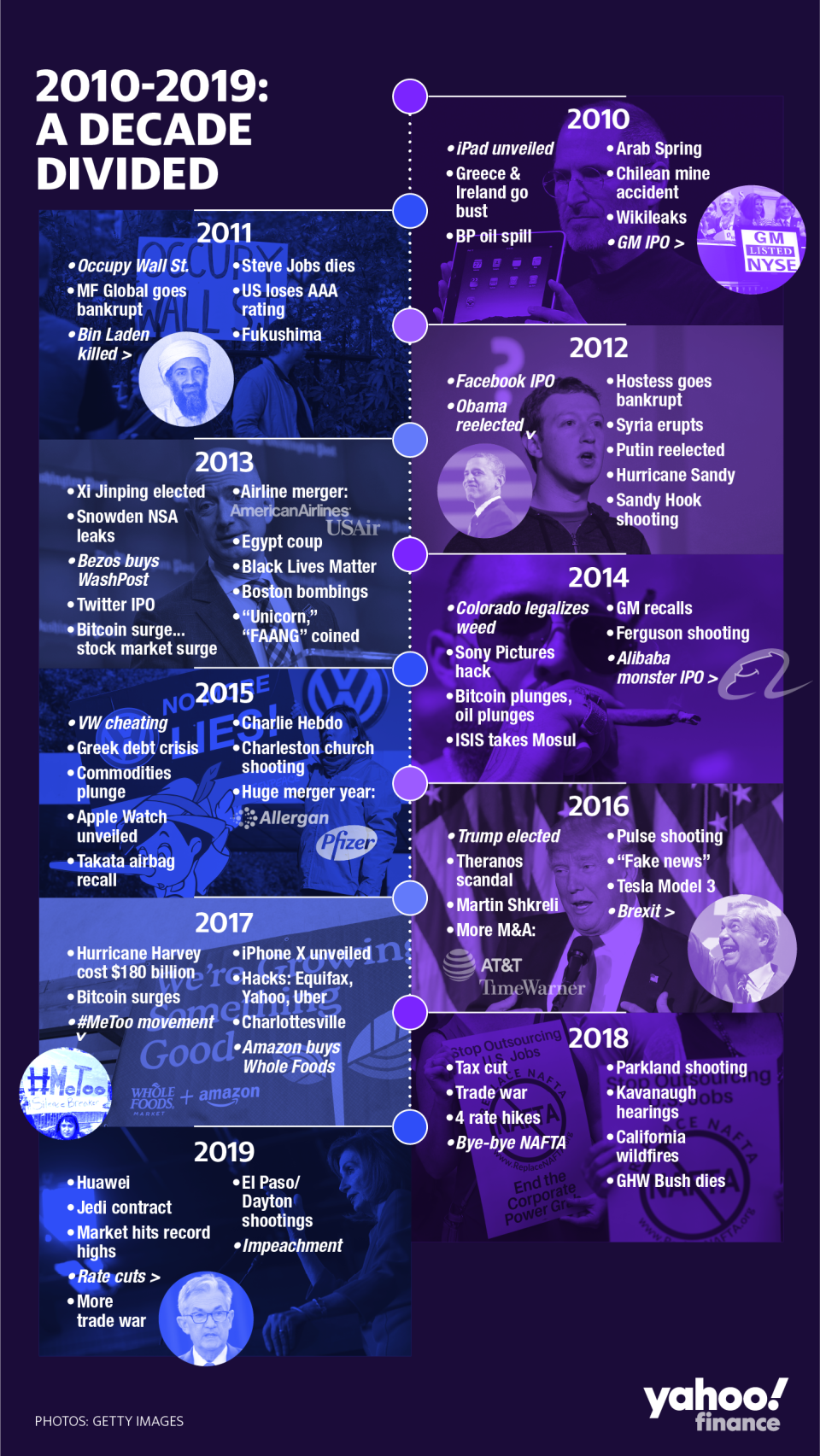

It seems apt right now to recall Lincoln's invocation of a house divided, as we are once again a nation at odds with itself, a state of affairs that has come to pass mostly over the previous 10 years. Just after Donald Trump was elected in 2016, a Gallup poll found a record high of 77% of Americans perceived the nation as divided. And it's not just here in the U.S. Our entire planet, humanity writ large, is more polarized, more pulled apart, today than it was 10 years ago. Though many of us have led ordinary, fulfilling lives unaffected by paroxysms of politics, that division and dividing up, tearing us apart in ways many of us wouldn’t have imagined a few years earlier, has been the defining trend of the past decade.

The American presidency perfectly mirrors all of this, with Obama in the White House for 70% of the decade and his polar opposite, Trump, for the remaining 30%, an ideological see-saw not seen since we flipped from Herbert Hoover to Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. Given that this splitting up has been the predominant trend of the past 10 years, the 2010s might best be called a Decade Divided.

Even an assessment itself of the decade must be, well, mixed — and also oh-so carefully considered. Every sentence of this story I write has the potential to be politically charged in a way that wouldn’t have been the case previously. I know from experience. Ten years ago I wrote a cover story for Time Magazine, entitled The Decade from Hell. While there were all manner of tough calls to make when it came to assessing a pretty ugly decade, in no way did I feel the pressure of the piece being judged on a partisan basis that I feel today.

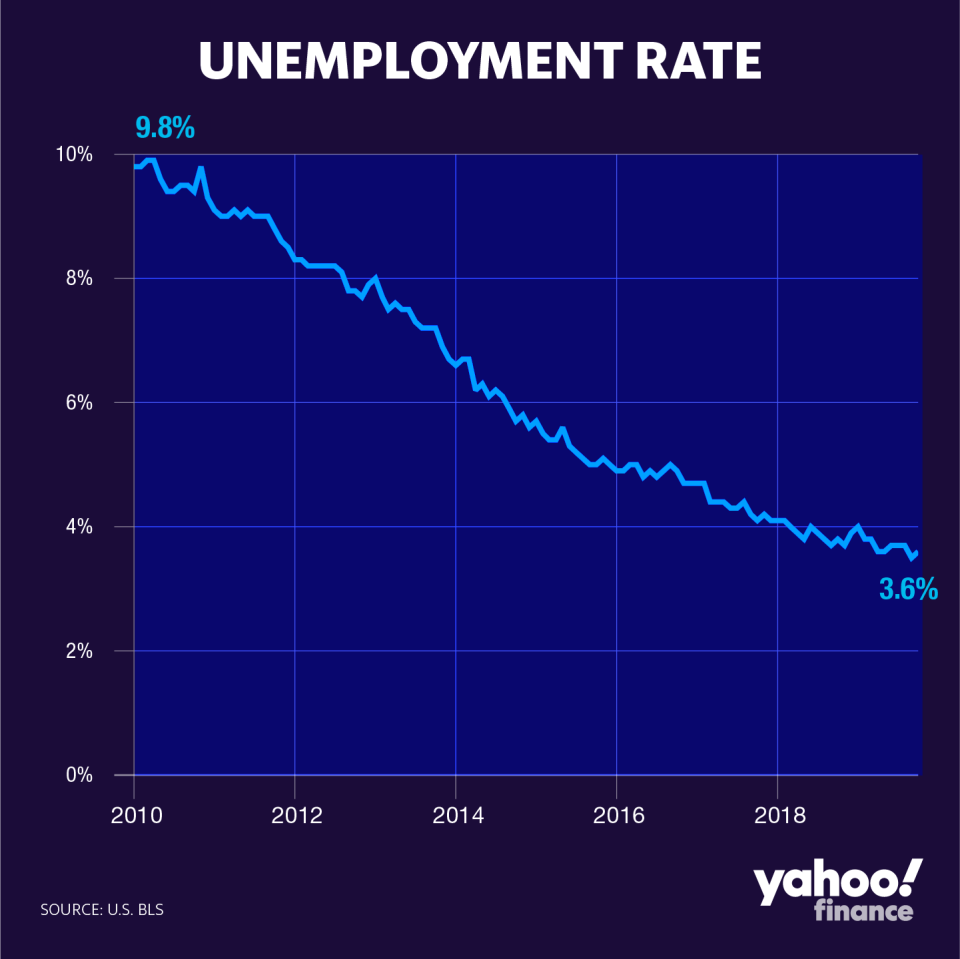

And yet, despite all the tumult — and as ironic or strange though it may seem — the U.S. economy went on a decade-long joyride, recovering from the Great Recession of 2008-2009 and then some. Unemployment plummeted, declining from 9.8% at the start of the decade, to today’s level of 3.6%, (a 50-year low). The stock market soared a stunning 175% over the decade — yes, close to a triple — and is now at record highs.

It was remarkable to see how resilient our country was in withstanding the worst economic downturn in 80 years. Yes, it has been a long slow climb back, which maybe shouldn’t be a surprise given how deeply we sank. But it certainly rewarded those who followed the advice given by Warren Buffett in an October 2008 New York Times op-ed, “Buy American. I Am.” He wrote: “…the market will move higher, perhaps substantially so, well before either sentiment or the economy turns up.” And it did.

British historian and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford, Niall Ferguson, reminded me that if you had held onto stocks all through the downturn of 2008-2009, you’d be sitting pretty right now. “And if you were long the FAANGs, you absolutely aced it,” he told me, referring to the tech stocks Facebook (FB), Apple (AAPL), Amazon (AMZN), Netflix (NFLX), and Google (GOOG, GOOGL).

Sometimes it pays to be patient.

“The economy is a battleship slow to turn,” says Rick Perlstein, author of “Nixonland” and “The Bridge,” among other books on the U.S. conservative political movement. “Presidents get credit or blame for the state of the economy when people go to the polls, but it often has nothing to do with decisions they made.”

The great economic expansion of the 2010s touched all of us in different ways and to varying degrees. If you are a member of the shareholder class, or were able to buy a bunch of stock, you benefited enormously from the bull run. You may have been able to climb up the economic ladder, as Americans are now working like never before.

But millions are having a hard time keeping up. It’s a fact that not everyone shared equally in the prosperity, and that on a percentage basis more people fell behind, as the decade has been marked by a widening of income and wealth inequality.

“Not everybody fares as well as everybody else,” says Fenaba Addo, assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a visiting scholar at the St. Louis Fed’s Center for Household Financial Stability. “It tends to be black and brown communities that can’t get the full rewards of growth the economy is experiencing. Black unemployment rate is still the highest if you compare it across race and ethnicity.”

That lack of equality goes a long way to explaining why so many of us felt so bad when things were getting so good.

‘The future does not belong to the globalists’

One result of this economic anxiety has been a rise in political populism here in the U.S. and around the globe — with leaders like Donald Trump, Britain’s Boris Johnson and China’s Xi Jinping assuming power. “It was predictable, political backlash after the Great Recession,” says Ferguson, author most recently of “The Square and the Tower: Networks and Power, From the Freemasons to Facebook.” “Even though it took a little time to take shape. We clearly passed the high-point of globalism.”

No doubt, globalism is in retreat, or at the very least stalled out, not only highfalutin Clintonesque, Davos pontificating, but also in terms of tangibles, like trade, immigration, and tourism. The U.S. issued 45% fewer visas to Chinese travelers to America for the 12 months ending in September than it did for the same period ending in September 2016. Addressing the United Nations General Assembly in September, President Trump articulated this new wave of anti-globalism, which he is both riding and driving:

“The future does not belong to the globalists. The future belongs to patriots,” the president said. “Looking around and all over this large, magnificent planet, the truth is plain to see. If you want freedom, take pride in your country. If you want democracy, hold on to your sovereignty. And if you want peace, love your nation. Wise leaders always put the good of their own people and their own country first.”

As Trump says, take a look around the globe and besides Johnson and Xi you see Vladimir Putin, Rodrigo Duterte, Narendra Modi, Jair Bolsonaro, and Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Yes, Emmanuel Macron, Justin Trudeau, Angela Merkel (for a few more months), and Shinzo Abe are still leaders too, but there’s no doubt which side has the weight and momentum.

Ferguson calls much of this movement “populism without a bite,” as Trump and Johnson, to name two, haven’t really enacted populist agendas. Still makes you wonder: Is this a temporary pullback from the trend of increased globalism we’ve experienced since World War II, or a full-stop reversal?

And maybe this is all … unfair? “When people criticize [globalism] they’re throwing that in the face of evidence,” says Jagdish Bhagwati, professor at Columbia University and senior fellow in international economics at the Council on Foreign Relations. “They attribute inequality to liberalization, completely ignoring the fact that inequality would’ve been worse if not liberalized.”

The decade of the protester

Fair or not, the globalism-populism tug of war is behind — to one degree or another — some of the most powerful movements and trends of the decade, from Occupy Wall Street, to the Tea Party, to #MeToo, to Black Lives Matter. Each one, depending on your perspective, may be hugely positive and liberating, but all are disruptive.

Writer and radio host Kurt Andersen also wrote a cover for Time, not long after mine, only his was for Time’s Person of the Year, 2011, which was “The Protester,” and the piece highlighted the Arab Spring and demonstrations in Russia and Spain, as well as Occupy Wall Street in the U.S. “I think you could make the case that it was a really a decade of ‘The Protester,’” Andersen told me. “2011 was just the beginning. Trump is a protester, the #MeToo movement are protesters.” And right now, there are more protests in South America, Lebanon, and Iran. And there are various protests against Big Tech too, (more on that later).

Why do these protests happen when they do? “There’s a small break in the dam and then the dam absolutely collapses,” says Claudia Goldin, professor of economics at Harvard University. “Only with a fair amount of distance can we historians can say, ‘Uh huh, I understand why the Civil Rights movement occurred, the women’s movement occurred, pro-democracy movement.’ One has to think hard and think harder again, why you get these abrupt changes.”

There was anger too coming from the fact that after all the carnage created by the financial industry in the Great Recession, not a single senior banker went to jail. Not one. Contrast that with the tech bubble (Martha Stewart went to prison!) or the Enron era. Bernie Ebbers, for instance, the disgraced former CEO of Worldcom, is still incarcerated, currently at a federal medical facility in Fort Worth, Texas. Ebbers began serving his 25-year sentence in 2006 and won’t be eligible for release until July 2028, when he will be 86 years old.

No wonder then it was a decade for the protesters and disruptors: Julian Assange, Jack Dorsey, DeRay McKesson, Elon Musk, Malala Yousafzai, Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning, Gretchen Carlson and Alyssa Milano (and Tarana Burke before her), Colin Kaepernick — and yes, Donald Trump and maybe in a sense, Xi Jinping, too.

And speaking of Xi, his country’s president for the foreseeable future, there’s the rise of China, which was hardly surprising — we’ve seen it coming for decades. And yet, as that nation’s GDP and power now rivals that of the United States, it’s still shocking given the scale and speed. And now at the end of the decade, the symbiotic Chinese-American relationship — Ferguson calls it Chimerica — is being decoupled before our eyes, with massive consequences in terms of, at the very least, prices and availability of goods and services.

The 2010s were not your parents’ decade. It was not a decade for the faint of heart. It may even have been the decade they warned you about.

For some it was a great decade. Tom Brady and the New England Patriots had an amazing run. So too the Golden State Warriors, Minnesota Lynx, UCONN women’s basketball, Maryland women’s lacrosse, and North Dakota State and Alabama football. It was an awesome decade for Rihanna (the most No. 1 singles this decade, nine), and runners up, Katy Perry and Bruno Mars. It was huge for Jack Ma and Alibaba (BABA), which did a $25 billion IPO in 2104, the biggest of all time. The decade was kind to Las Vegas and Phoenix, which were both battered by the Great Recession and went on to become two of America’s fastest growing major cities.

‘My life has been good. I’ve lived it well’

And for millions and millions of average Americans, the 2010s were pretty good, too. They grew up, went to college, got married, had kids, retired and sadly saw family and friends die after long fruitful lives.

Take Jace Ditmyer, 11. I first met Jace 10 years ago when I was writing that Time Magazine, entitled “The Decade from Hell.” The cover image was actually of Jace, barely one years old, crying like hell, presumably about the decade from hell. Earlier this year, Jace’s mother, Tamara Flannagan-Ditmyer, tracked me down and asked me if I’d like to meet Jace and maybe interview him. Great idea.

I recently sat down with him and asked, among other things, how the past decade treated him. While I could see Tamara roll her eyes a bit — she has strong political opinions — Jace nonchalantly told me things were great:

Jace: “My life has been good. I've lived it well. Nothing… Well, I went to Disneyland.”

Tamara: “Disney World.”

Andy: “How would you rate the past decade on a scale from one to 10?”

Jace: “That's hard. Nine or an eight.”

Thank goodness Jace and millions of other children have been mostly oblivious to the more unsettling aspects of the decade.

A decade of violence

And in fact the decade started off well enough. Remember the Chilean miners being rescued in 2010? Thirty-three of them, 2,300 feet underground freed from the clutches of death after 69 days, (foreshadowing the equally dramatic Thai cave rescue eight years later, replete with an Elon Musk controversy). Osama bin Laden was killed in 2011 (as was ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in October, bookending the decade). Less visible, but hugely important over the past decade, was the economy digging itself out of the Great Recession, with the bottom coming in the spring of 2009.

But again, as is typical of the decade, the flipside of the card was right there, too. Let’s just get right to the worst of it, that being the epidemic of mass shootings in the United States. These events are universally recognized by these proper nouns; Sandy Hook, Parkland, Pulse nightclub, Las Vegas, El Paso, Charleston, and so many more, thousands shot and many hundreds of innocents murdered by sociopaths with guns. And yes the shootings were more deadly and more frequent in the past decade than ever before. And yes we still argue about why and what do about them. The rest of the world shakes its head.

Some of those shootings and deaths were domestic terrorism, and add to them the horror of the Boston Marathon bombing and its aftermath, and the national disgrace of a neo-Nazi rally that turned deadly in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017. The majority of gun-related deaths, though, result from suicide — which is on the rise and is now the second leading cause of death among 10- to 34-year-olds.

Adjacent to these deaths are the killings of African Americans (mostly men), often at the hands of police; including Freddie Gray, Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, and Eric Garner, crimes often captured on mobile phones. Janelle Monáe’s 2015 “Hell You Talmbout,” tells their story. Black Lives Matter and NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick kneeling during the national anthem, were all about those deaths too, which sometimes engendered further backlash and repercussions, and even made watching football, for a time at least, politicized.

The domination of big tech

But honestly, the biggest disruptive force of the decade was technology. Just think about it. True, the FAANG companies — Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google — along with their Chinese BAT counterparts, Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent, were all born before this past decade. So too, Kurt Andersen reminds me, were the most impactful tech products, the iPhone, Google search, YouTube, Kindle and Twitter. (Notably, Apple co-founder Steve Jobs died in 2011).

And yet this was the decade big tech came to truly dominate. It’s almost impossible to overestimate the influence of these companies; shopping, entertainment, communications, banking, search, and elections, are all being completely redefined — not by governments or international tribunals — but by these companies. Which maybe isn’t surprising given that the market capitalization of the FAANGs at $3.642 trillion is almost as big as the GDP of Germany. Maybe it’s also not surprising that many consider there to be four big blocks of socio-economic power in the world — the U.S., Europe, China, and the big tech companies. Or that Denmark became the first country to appoint an actual ambassador, Casper Klynge, to Silicon Valley.

If I had told you a decade ago that the president of the United States’ primary means of communicating to the world would be on a smartphone app that was created and is run by a man who every morning meditates for an hour, takes an ice bath, and breakfasts on salt juice, you wouldn’t believe me. And yet here we have President Trump, more than 11,000 tweets later, spouting away on the iconoclastic Jack Dorsey’s platform.

Tech helped create and foster the aforementioned Arab Spring, which led to revolutions in Egypt, Libya and Syria, which induced Benghazi, ISIS, the refugee crisis and exodus and terrorism in France and England and on and on and on. Of course only some of this — for better or worse — can be laid solely at the feet of the tech giants, and yet we know those companies played a significant, undetermined and unintended role.

Another consequence of the tech boom has been to exacerbate divisions in our global society, and it has done so multiple ways. For those who can afford the most effective, efficient and expensive tools — $1,000 iPhones, Teslas (TSLA), Pelotons (PTON), and every streaming service under the sun — life has become a post-industrial fantasyland. Those who can’t afford them are increasingly living in a parallel, lesser world. So too, with the corporate employees at the leading tech companies, who have become another class of citizen, enjoying compensation, perks, and a lifestyle unimaginable to most of the other 99%. And finally, technology and especially social media have splintered us into various political camps and echo-chambers increasingly characterized by an us-versus-them mentality, easily exploited by trolls, political operatives and state-sponsored actors who seek to divide us further to achieve their nefarious ends. The problem with the term “fake news” is that we can’t figure out what’s real and what isn’t, either because it’s so clever, or because we disagree over what it is. This is a real problem.

Technology gaps are of course economic, but also geographic not only in terms of countries but also for instance in the United States, when it comes to urban versus rural. It is also one of age of course, where younger digitally native people have entirely distinct skill sets, language, and priorities from older folks, based on familiarity with technology. The implications are laid bare when Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg testifies before Congress, leaving both sides to declare that the other side just doesn’t get it. Guess what? They’re both right!

In the end and at their core, tech companies have these four problems:

They have built platforms they don’t fully understand.

They have built platforms they don’t fully control.

They consult with a limited, insular cohort.

They underestimate or do not acknowledge the first three points.

Tech of course also has helped us achieve all sorts of marvelous accomplishments. Of the many industries roiled by technology this decade, cars and transportation, are at the top of the list. In 10 years we went from a bankrupt Detroit, to GM’s (GM) IPO in 2010, (for the record, the stock traded at $34 the first day, it trades at $36 today), to the revolutions and wonder of Elon Musk’s Tesla (and other electric vehicles coming online). Then there’s Uber (UBER) and Lyft (LYFT). And Waymo and driverless cars. It’s head-spinning stuff and very clearly early innings, too.

New technology has essentially increased the global supply of oil and gas by allowing drillers to access previously untappable supplies, like shale gas in the U.S. This has actually had largely negative effects on nuclear power — the Fukushima accident didn’t help, either — and renewable energy in its many forms. Still, Tesla has managed to sell 720,000 cars (the company’s number) since 2012. And you now see windmills from Maine to California.

Cryptocurrency, shadow banking, and massive hacks

And what about bitcoin, blockchain, and cryptocurrency, all of which came of age during the past decade. Crypto soared — remember when bitcoin hit $20,000 in late 2017? — crashed, rose and sank again. Who among us can really claim to fully understand these new forms of value exchange? And if you can, please tell us what this means for banks, governments, and society? Charlie Munger called it rat poison, while others are betting billions that crypto will revolutionize everything. It’s very unsatisfying and not so helpful to say the answer probably lies somewhere in the middle. And yet it probably does.

“We have more regulation for the regulated part of the finance system and some of the business has gone to the more unregulated part,” says Lisa Cook, associate professor of economics and international relations at Michigan State University. “Fear of another looming financial crisis is growing, in hedge funds, cryptocurrencies, on the shadow banking sector.” Cook also talks about how powerful forces use of tax evasion. Both the Panama Papers and Paradise Papers illuminated some of the mechanisms of how tax evasion happen.

Speaking of that dark, virtual world, massive hacks against the public sector and consumer companies like Equifax, (our parent) Yahoo, and Uber are unsettling mostly because we feel completely powerless to stop them and we know this vulnerability can’t be easily addressed. So too, cyberterror and cyberwarfare as practiced by Russia, North Korea, China, Iran — and no doubt the U.S. is likely in its early days. Another thought scary to consider.

A new legal drug and the scourge of opioids

And what does it say that during everything that went on in the 2010s, we decided we needed a new, legal drug? Or to put it more accurately, to legalize weed (in some states), a plant that humans have been ingesting — going back to the Indian subcontinent — for some 4,000 years, but made illegal only in most of the world over the past 150 years. Legalization has been creeping along for years, but hit a tipping point in 2014 when Colorado’s recreational marijuana stores opened for business. It’s really about economics. After spending untold billions locking up pot offenders and losing billions more to illegal sales, state governments and Canada too, realized the downside of legalization (and yes there is a downside), was outweighed by the benefits of locking up fewer people, and by the way, harvesting tax revenue from marijuana. The 11 states where recreational weed is legal reaped some $1 billion in taxes last year.

While some argued vociferously for legalization of one drug (weed), at the same time our country was paradoxically being devastated by another class of drugs; opioids, heroin, and fentanyl. So terribly impactful was this scourge — hundreds of thousands of Americans have died — it actually contributed (along with suicide and alcoholism) to the decline in life expectancy in the U.S. for the first time in 100 years.

Climate change — now the generally accepted phrase — also became more widely acknowledged as fact and a real threat. Its effects were likely felt throughout the decade, both in terms of catastrophic storms; Superstorm Sandy and Hurricanes Harvey, Maria and Irma, (three of the top 10 years with the most hurricanes were in the past decade), and drought and fires in for instance California and Australia. Climate change activism swelled as well, with global protests — often orchestrated by young people — in Sydney, New York, and Mumbai, even disrupting the Yale-Harvard football game! It’s telling that young Jace knows exactly who 16-year-old climate activist Greta Thunberg is: “I like Greta Thunberg. I've seen like the whole march about Greta Thunberg and it was pretty good,” Jace says. “...the polar bears are living on ice caps that are not freezing now. So all the little cubs and polar bears are now trying to survive…”

A rebound decade with comparatively slow growth

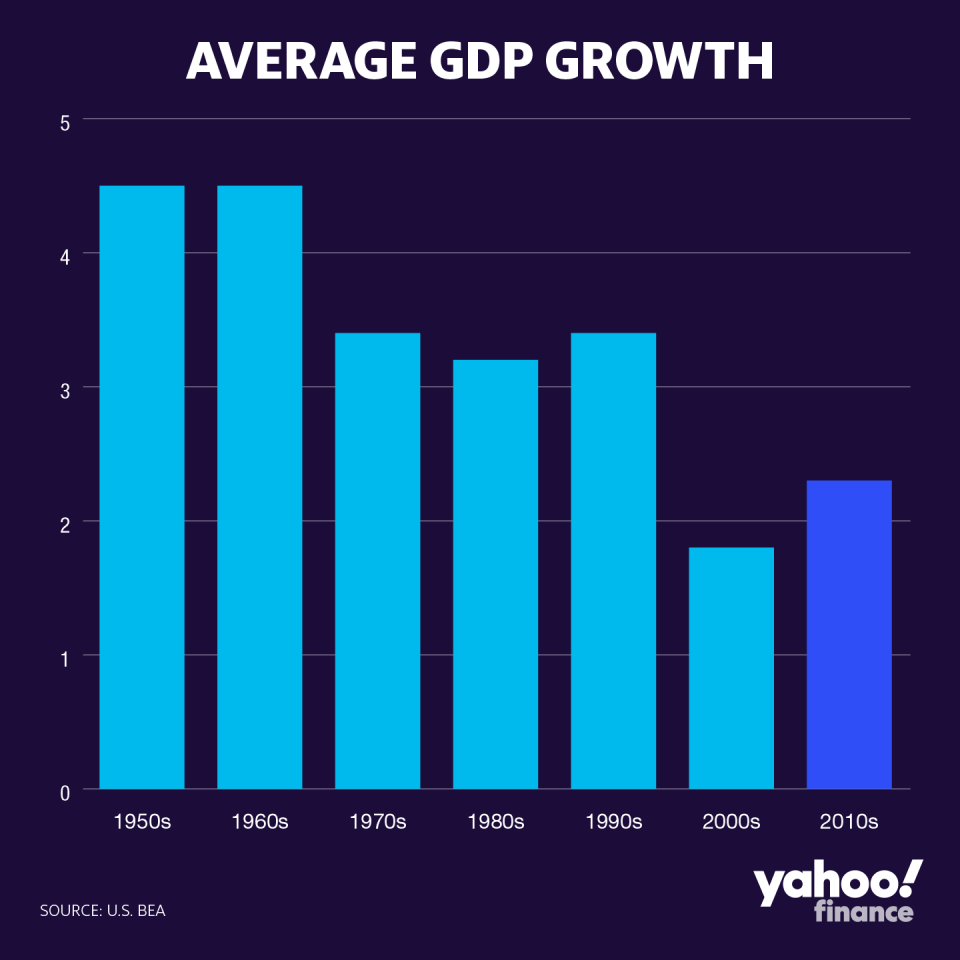

But let’s leave aside climate change, and drill down and look at some hard numbers. The economy grew 2.3% on average this decade, which looks good compared to last decade’s paltry 1.8%. But if you look back at previous decades, our current growth rate pales. In the 1950s and ‘60s, the U.S. was growing 4.5% per year on average, (we were practically China back then), and even in the difficult 1970s, we logged 3.4%.

Why the slowing? Maybe we’re measuring the wrong thing, Nobel laureate in economics and professor at Columbia University, Joseph Stiglitz, wrote in an opinion piece in the Guardian last month.

“So what if GDP goes up, if most citizens are worse off?” he wrote. Later in the piece, he added, “It is clear that something is fundamentally wrong with the way we assess economic performance and social progress.”

Economists say in decades past, faster population growth as well as big infrastructure projects, like the national highway system, boosted growth. They also say productivity gains have slowed, though some critics say the dismal scientists aren’t measuring that correctly either and are ignoring efficiencies gained by using mobile phones, for instance.

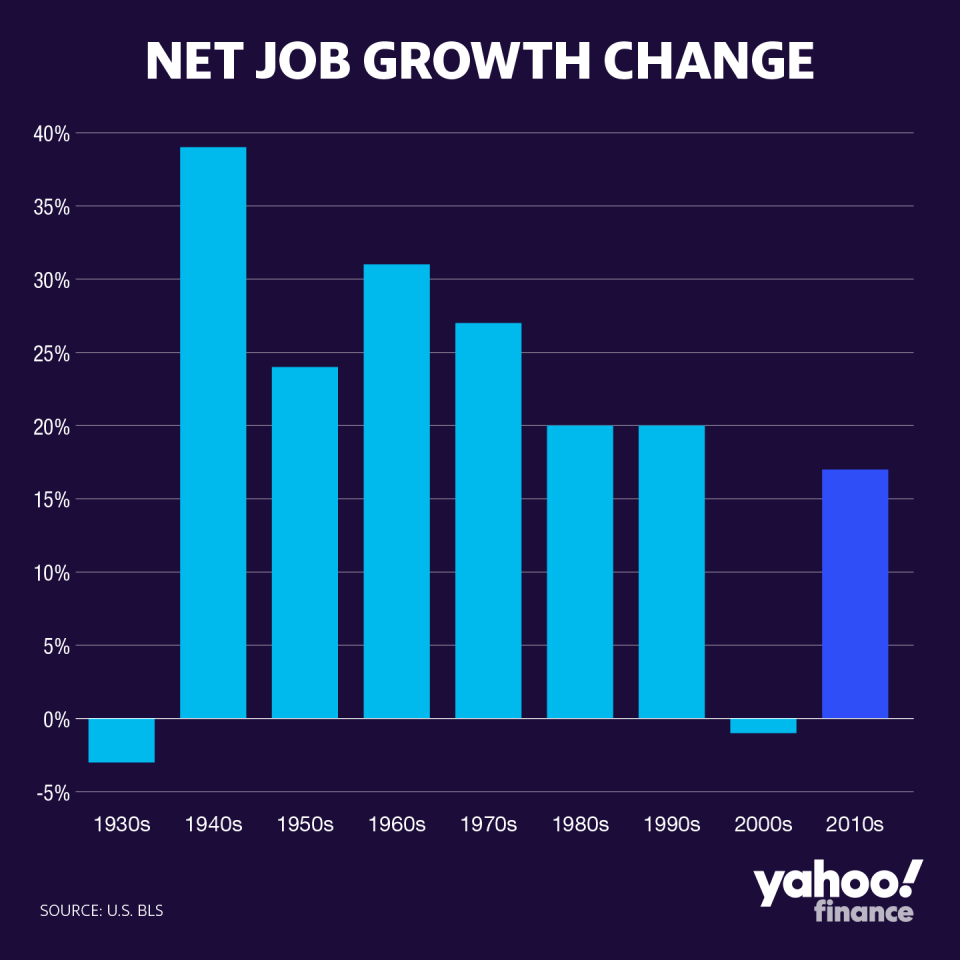

Not surprisingly perhaps, job growth mirrored this sluggish growth trend. Yes, the unemployment rate declined precipitously. Nearly 22.3 million new net jobs were created in the past decade, and this was much better than the 2000s, when we actually lost 956,000 jobs. But while the 2010s was a rebound decade and big in terms of the absolute number of new jobs created, it was below trend historically in terms of percent change, up 17%, versus the 1950s through the 1990s, when job growth was 20% and above.

“This 3.6% unemployment rate today, is really different than a 3.6% rate in 1960 when jobs had benefits like tuition assistance and pension plans,” says Martha Olney, a professor of economics at the University of Berkeley. “There’s more tenuousness to jobs today. They’re not lifelong jobs. People are working at Uber, or startups, not permanent jobs that will provide them the opportunity to build a middle class life for themselves and their children.”

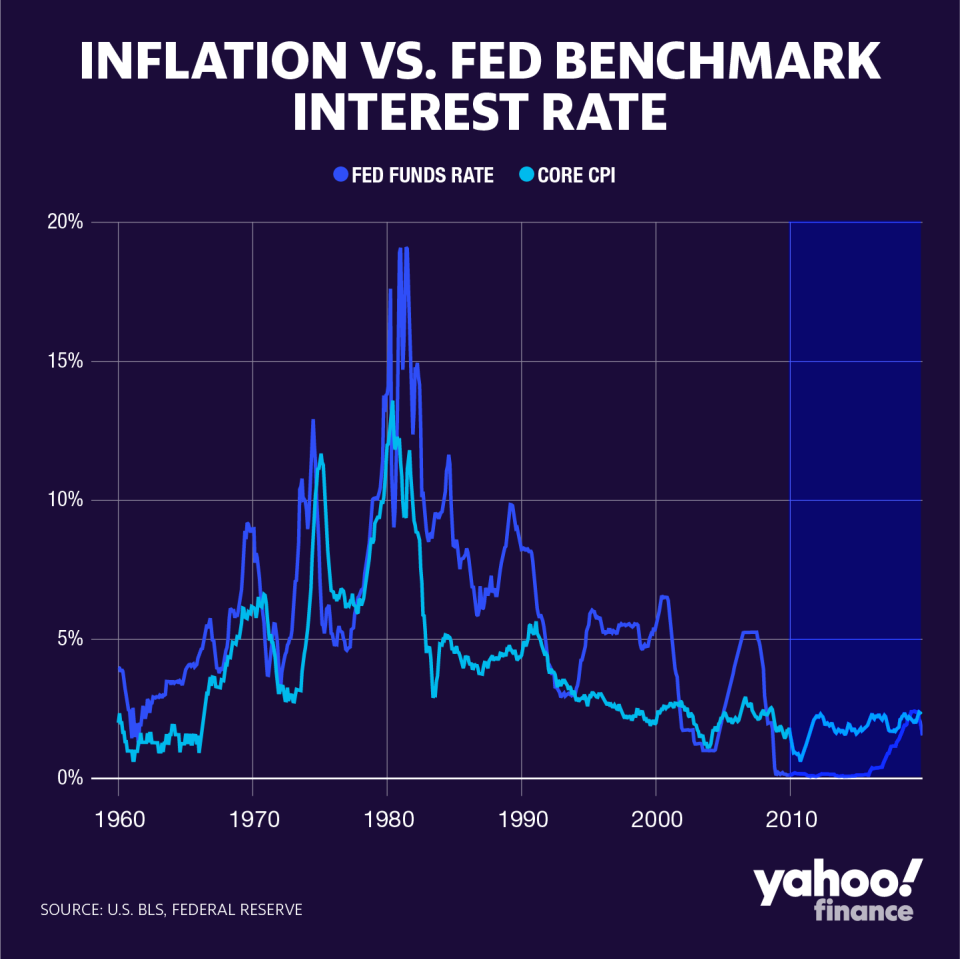

Interest rates, which remained stubbornly low, also matched the slow growth of the decade. The Fed funds fell below 1% in October 2008 and did not recross that threshold until June 2017. In October of 2018 it pierced 2%, only to then fall back this fall as fears of slow growth again dogged the global economy. Fed Chairman Jay Powell, who became a whipping boy for President Trump, cut rates three times in 2019, the first cuts in more than a decade. As Trump pounds the table for more rate cuts, much of the world now wrestles with the scary unknown of negative rates.

With rates so low, growth so dear and regulation on the friendly side, it’s no wonder that CEOs bought other companies at record rates during the decade. Three of the five biggest deals of all time — H. J. Heinz and Kraft, Anheuser-Busch InBev and SABMiller, and Dow Chemical and DuPont — and scores more mega deals went down in the 2010s.

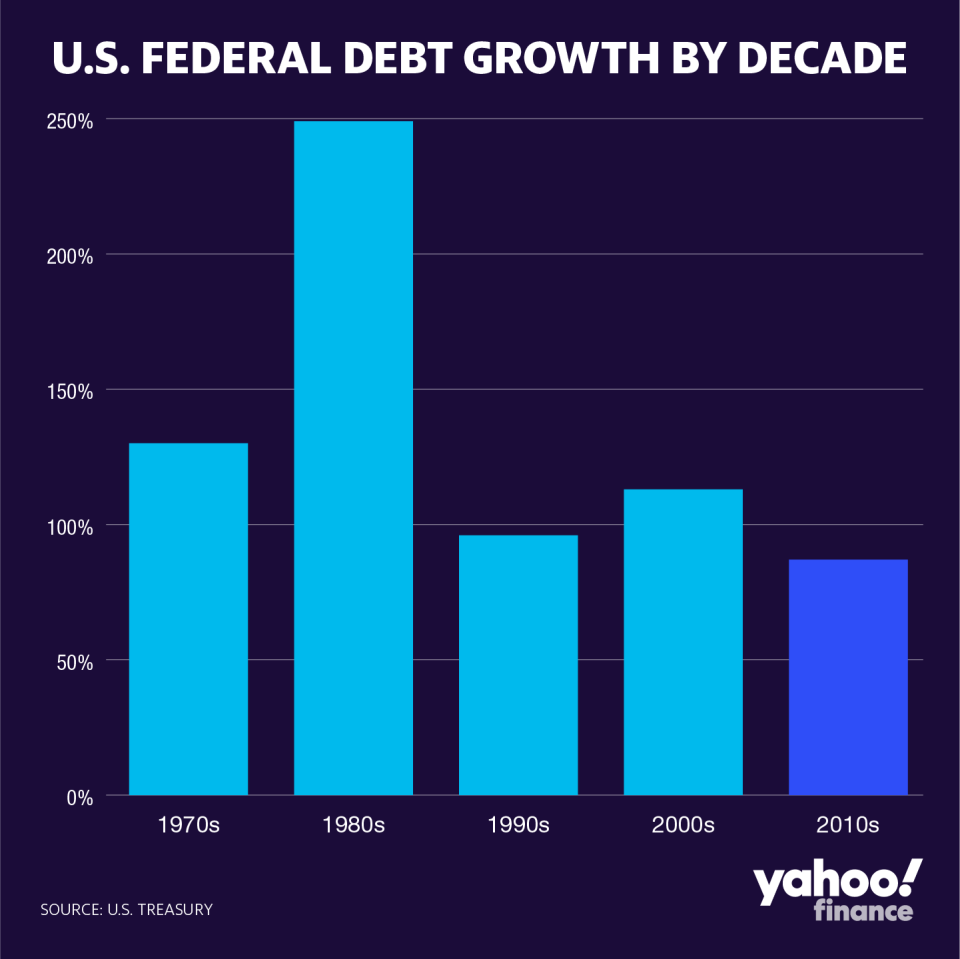

The numbers suggest one strong unassailable point, which is, for now at least, the U.S. and the world are in a slow growth phase. That may turn on a dime, based on some unforeseen development, but will more likely linger. So with all that sputtering, how come the stock market was up 175% last decade?

It’s all about reverting to the mean. You may recall, or have tried to forget, that in the prior “Decade from Hell” (the 2000s), the market actually declined 26%. That’s a huge period of underperformance, (stocks usually appreciate some 9% per year). And that’s really why the market took off over the past 10 years.

When writing my “Decade from Hell” story 10 years ago, I interviewed NYU business school professor Richard Sylla, who predicted this decade’s outperformance. "Usually when you've had a really bad decade like this one, the next decade turns out to be much better for investors," Sylla told me back then. "Probably 10 years from now, people who are investing today are going to have fairly nice returns."

‘I don’t think the market will do as well’

I checked back in with Sylla recently, (he’s now professor emeritus,) and he acknowledged that regarding last decade, “it turned out I could have been more optimistic,” he said with a chuckle. So how about the next decade? What does the soothsayer Sylla say now? He’s not as sanguine. “It’s maybe not like 2009. Stocks seem richly priced. I don’t think the market will do as well.”

So where do we go from here? Recession? Sure, at some point. But there are bigger forces to consider as well, such as; the U.S. frenemy relationship with China — Ferguson calls it Cold War II. Also that nagging inequality problem, populism versus globalism, and technological breakthroughs in AI, 5G, genomics, and life sciences.

What will happen in the world over the next 10 years?

David Rosenberg, Gluskin Sheff chief economist and noted market bear is for one, worried. Speaking about disunity, he says, “All we’ve seen is happening when we have peak equities, peak economy, trough unemployment. Imagine when these revert. That’s not a pretty picture.”

It’s true we may not be starting from such a great place.

“The idea you can have a stable economic recovery marked by inequality was a fallacious presumption,” says Rick Perlstein. “You need a strong middle class to have a strong society. The way economic policy was pursued didn’t prioritize that.”

But ask Rosenberg to look further out and he gets more positive. “This is where I’m optimistic. My hope is that we’ll spend the next 10 years correcting the mistakes we’ve made.”

Consider again Lincoln’s speech, where he predicted that the house divided would not stand. He was right of course, but not before our differences were hashed out in a horrible, nearly existential Civil War, which killed 620,000 Americans (the equivalent of 6 million today).

Not long ago I asked Warren Buffett about our differences, and he was loath to sound alarmist. “We fought the Civil War and I would say we were more divided up in the Vietnam era too, but we came back together and we will come back together again this time too,” Buffett told me.

Buffett’s probably right, but the question is how? Does it just happen naturally over time? Or do we have to work at it?

“I think those of us not throwing up our hands and saying nothing can be done, we will be vindicated,” says Lisa Cook, associate professor of economics and international relations at Michigan State University. “That progress — economic, social, political — comes typically in small increments.”

So, we can wait for our social order to self-correct and hope for the best. Or we can look to not only grow our economy, and reverse wealth inequality, but also to try to reach across the aisle, listen to each other and resist the forces that seek to divide us. As Lincoln showed us, the alternative is almost unthinkable.

Andy Serwer is editor-in-chief of Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter: @serwer.

Read more:

Facebook's Zuckerberg and Sandberg are this involved with the company's content issues

Negative interest rates are coming and they are downright terrifying

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.