How pros are advising clients in this bizarre world of negative rates

Global economic uncertainty, low inflation, and unusually easy monetary policy have caused about $13 trillion worth of bonds to have negative yields, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch. That means investors lose money by holding onto a bond — a traditionally low-risk investment that often offers fixed interest rate payments.

Since the UK decided to leave the European Union (aka Brexit) last month, that estimated total jumped by $1.2 trillion, according to a recent report from Citi Research. While negative yields were once rare, they’re becoming increasingly common and even more so in the wake of the Brexit. Before Brexit, only 29% of the bonds tracked by Citigroup World Government Bond Index (WGBI) had negative yields; as of July 6, it was 35%.

This is the result of central banks, that have been imposing negative interest rates to encourage borrowing (meaning you lose money if you lend but gain money by borrowing). Because interest rates set by central banks influence other fixed-income securities, negative yields on government bonds have also become part of the “negative universe” as Citi calls it.

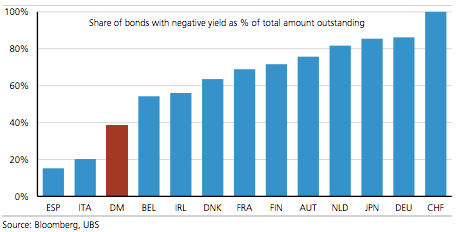

As can be seen from the UBS chart above, these negatively yielding bonds are primarily located in the European Union and Japan.

Both of these economies are a big part of the bond market, with EU governments having $14 trillion of debt in total. Japan may just be a single country, but it is still a massive bond issuer, with $10 trillion of debt.

Even longer term bonds are starting to be affected, with Japan’s 20-year bond yield going negative for the first time in history two weeks ago.

What the pros are telling clients

These negative bond yields are spread out across all the EU countries, particularly the stronger ones, such as Switzerland, Germany and France, with nearly 40% of developed market bonds going negative across the world. However, even the weaker European economies, such as Spain, Italy and Ireland have some bonds with negative yields.

As a result, UBS analyst Bhanu Bajewa suggests that emerging market bonds may be the best bet for investors. These come with positive yields, but a greater risk of default. “Investing in these fixed income securities at this price, and holding them to maturity, one knowingly loses money with certainty. The risk of losing money on weaker credits looks less bad in comparison,” argues Bajewa.

Investors do have to be selective when looking at emerging market debt though; some countries may be too risky. UBS considers Brazil, Mexico, Poland, and Malaysia to be especially attractive.

At the same time that money is piling into these lower-risk bonds, riskier investments such as equities are also surging. The S&P 500 seems to be hitting new all-time highs every other day. This is because less risk averse investors are desperate for any sort of return, leading them to buy stocks, regardless of valuation. This worries the analysts at Goldman Sachs.

Generally, investors are advised to have a balanced portfolio of bonds and stocks, as this decreases the risk of their entire portfolio being hit by negative economic conditions. However, with equities and bonds rallying simultaneously, both now have “expensive valuations” and are “vulnerable to shocks,” argues Goldman analyst Christian Mueller-Glissmann. These two factors combined mean that the potential return for investors in either investment is low right now, while risk is high.

As a result, Mueller-Glissmann thinks investors should go “overweight” cash, which essentially means that they should have a significant portion of their portfolio uninvested. Cash doesn’t provide any sort of return, but you can’t lose any money, unlike with stocks and bonds.

The negative yield phenomenon is so widespread in Europe and Japan partly because inflation is incredibly low in both places. In Europe, consumer prices are actually falling as a result of weak demand across the continent, while US prices are increasing at only a modest pace.

Interest rates have to compensate both for inflation and the risk of lending money, with the “real” interest rate equalling the interest rate subtracted by the rate of inflation. If the inflation rate is negative, bonds are more likely to be negative.

Both the EU and Japan also have massive, ongoing bond-buying programs, known as “quantitative easing.” This helps push bond yields down further, making them less and less attractive for investors.

—

Rayhanul Ibrahim is a writer for Yahoo Finance.

Read more:

From biomass to nuclear: The evolution of American energy usage since 1776

America’s big companies are about to repeat a financial crisis-era losing streak

As the stock market hits new highs, Wall Street is getting more skeptical

These trillion-dollar categories are driving Amazon’s growth

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance